Computing Science

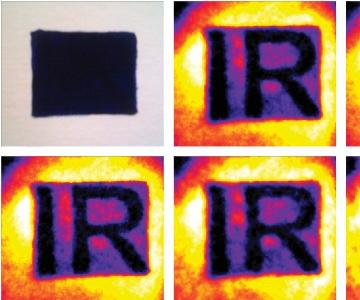

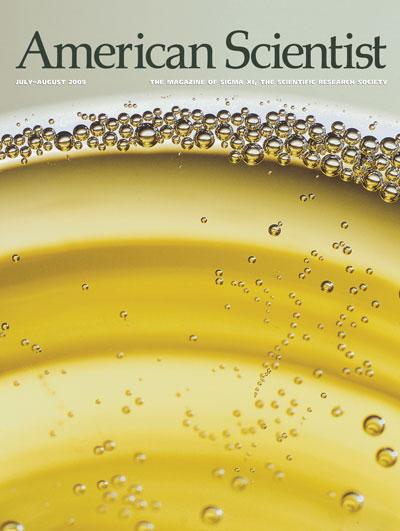

Effervescence defines Champagne and sparkling wines. Elegant bubble trains rise from nucleation sites—microscopic cellulose fibers—deposited on the glass. Free-floating particles, called fliers, produce swirling bubble streams, as can be seen particularly well in the top corner of the Champagne flute shown at left. Once bubbles reach the surface of the wine, some travel outward and accumulate in a collar of foam around the perimeter of the vessel, as shown on the cover. (The bands of color shown in the cover image result from the angle of the photograph and the shape of the glass, not from properties of the Champagne itself.) The bubbles create a dramatic display, but enologists wish to know how bubbles may affect the wine’s taste as well. In “Bubbles and Flow Patterns in Champagne”, Guillaume Polidori, Philippe Jeandet and Gérard Liger-Belair use lasers, dyes, microscopic particles and fluid dynamics to explore the role of bubbles in the movement of the wine inside a glass. Cover image is courtesy of Alain Cornu/Collection CIVC; image at left is courtesy of Guillaume Polidori.

Two bursts of human innovation in southern Africa during the Middle Stone Age may be linked to population growth and early migration off the continent

Too little attention has been paid to the statistical challenges in estimating small effects

Engineering inspiration arises from the structures of proteins

The Model T • American Pests • Flotsametrics and the Floating World

Click "American Scientist" to access home page