This Article From Issue

July-August 2009

Volume 97, Number 4

Page 344

DOI: 10.1511/2009.79.344

THE TROPICS OF EMPIRE: Why Columbus Sailed South to the Indies. Nicolás Wey Gómez. xxiv + 592 pp. The MIT Press, 2008. $39.95.

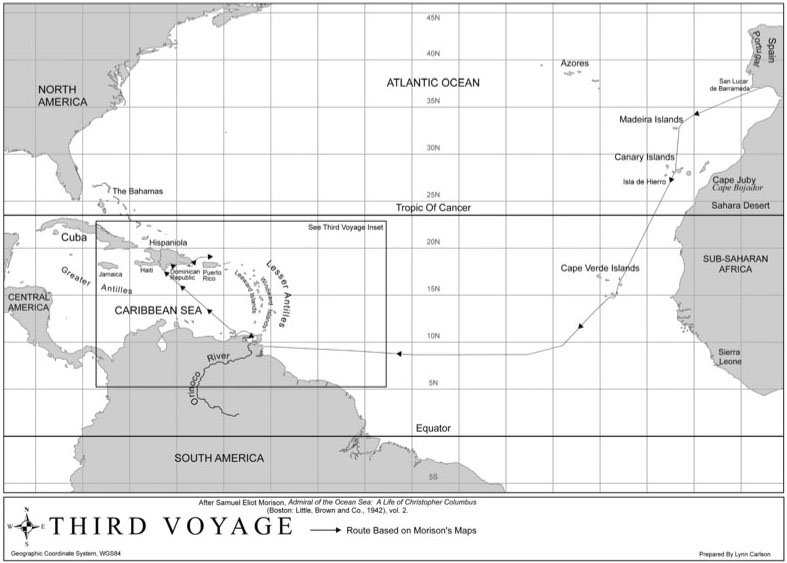

Nicolás Wey Gómez opens his learned and incisive study of cosmography and colonialism in the Age of Columbus with a simple observation: Christopher Columbus did not just sail west across the Atlantic in his search for a maritime passage to the Orient; he sailed south as well. The Genoese sailor’s westward movement across the Atlantic has long been seen as the essential vector in leading Europe toward its greatest colonial venture. But not enough attention has been paid to the fact that Columbus made a conspicuous move in a southerly direction, which allowed him to encounter the islands of the “Indies” and, on later voyages, the South American continent. By reconstructing the routes Columbus took, and by carefully analyzing his diaries and the manuscripts that he read and annotated, Wey Gómez shows in convincing detail how it came about that Columbus turned his prow toward the tropical portions of the globe as he conducted his famous voyages of discovery. His reasons for heading south and the geopolitical consequences of that move are the twin subjects of The Tropics of Empire, a hefty and impressive study executed with erudition, skill and considerable insight.

From The Tropics of Empire.

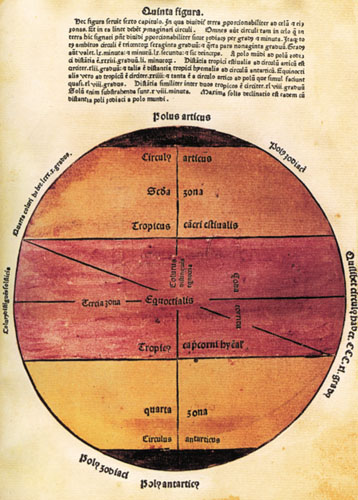

In Columbus’s day, ideas about the tropics were much influenced by the conceptions of ancient geographers and cosmographers, who viewed the earthly sphere as split into broad bands of temperature-specific climates: the frigid polar regions, a searing “torrid” belt around the equator, and between them, two comfortable temperate zones. These climatic zones were thought to determine human actions and characteristics, from the ethnic behaviors of diverse peoples to the contours of theological events, and it was understood that only the mildest climates were capable of supporting human habitation. Thus the civilized inhabited world lay in the temperate zone. Sub-Saharan Africa and India, which were in the torrid zone, “were . . . imagined as the hot, infertile, and uninhabitable fringes of the world.”

But was habitation in these more “torrid” climes truly unimaginable at the time of Columbus’s first voyage? After Portugal’s exploration of the African coast early in the 15th century, and especially in the wake of the Portuguese passage beyond Cape Bojador in what is now part of the Guinea Coast of West Africa, Europeans knew that ancient models were at least partially flawed. The equatorial regions of Africa were quite clearly inhabited and had been for some time. Columbus himself referred to dark-skinned people (who were generally called “Ethiopians”) living beneath the equator. In 1482, he visited the Portuguese fort of São Jorge da Mina on the equatorial coast of Guinea, where slaves, gold, ivory and pepper were traded. Afterward, he made a pitch to Dom João II of Portugal that he would likely find similar resources at the very same latitudes if the king funded him to sail west across the Atlantic to find a new route to the Indies. In the end, Portugal did not end up sponsoring Columbus’s venture. Instead, Columbus made his dramatic landfall under a Spanish flag, arriving at an island he called San Salvador in October of 1492.

Wey Gómez’s most significant contribution to Columbus scholarship is to emphasize Columbus’s specific interest in the tropics as a potentially exploitable place. He argues that it was not merely geographical happenstance that Columbus made an explicit turn to the south when he arrived in the Bahamas on his first voyage. Rather, it was a conscious gesture, an effort to “[ratify] the political terms of a geographic endeavor.” Correlating ancient geographical knowledge of the terrestrial sphere and the political impulses of early modern colonialism, Wey Gómez brings together two often-separated topics. The first is geographical discovery, which frequently hides behind myths of heroic and ingenious individuals; the second is the devastating impact of European actions on native peoples and places, which is often correlated with a second wave of zealous conquistadors, who exploited an already discovered New World.

Clearly, Wey Gómez does not impute heroic motives to Columbus’s interest in “southing” when he set out again after first making landfall. Instead, he claims that Columbus’s

subjection and enslavement of the peoples newly discovered near and within the torrid zone were deliberately intended to reenact Portugal’s own monstrous harvesting of human labor and natural resources along sub-Saharan Africa’s western coast.

That is, Columbus was consciously performing for Spain what he had already seen carried out by the Portuguese in Africa: an exploratory gesture to garner resources in the form of gold and human labor, in a world previously undiscovered and unexplored, which was thought in some traditions to be devoid of any human culture whatsoever. Wey Gómez posits Columbus as the precursor of a particularly sinister form of European expansion and as a geographical elitist who believed that the torrid zone—and the people who inhabited it—would serve Europe as an abundant and exploitable material mine.

The emphasis on Spain and Portugal’s interconnected histories during this period is a key strength of Wey Gómez’s approach. He recognizes that Spanish ambition and the intellectual traditions that spurred and supported the Crown’s interests did not stop at the borders of Castile and Aragon. Portuguese policies and treatises written by those under Portuguese tutelage were required reading for navigators and pilots during Columbus’s time, as much so as Arabic, Greek and Roman sources.

In the first chapter of the book, Wey Gómez presents the building blocks of ancient and medieval cosmological traditions through an examination of the central figures whose ideas influenced Columbus. Two of the most important were Albertus Magnus (1200–1280) and Pierre d’Ailly (1350–1420). Wey Gómez describes the European cosmological view stemming from antiquity as a “tripartite geography of nations” in which a people’s cultural characteristics related quite directly to their distance from or proximity to the torrid zone. Columbus was intrigued by this Eurocentric political model, and he even went so far as to paraphrase d’Ailly’s interpretation of Aristotle’s ideas about the influence of place: The residents of the south were held to be wise and prudent, whereas those of the north were stronger and more spirited. But it is the political lessons that Columbus drew from these observations that Wey Gómez emphasizes, pointing to a more nefarious use of cosmology and geography than previous scholars of Columbus’s voyages have been willing to ascribe to him. In Wey Gómez’s reading, it was because Columbus had been heavily influenced by ancient models that he insisted on describing the Taínos (the “tame” peoples he encountered on the island he named San Salvador) as docile and intelligent, and on depicting the Caribes (the peoples he found further south in the Lesser Antilles) as monstrous and cruel.

Columbus also drew inspiration from other medieval theories, including a Christian geography embodied most forcefully in the philosophical writings of Augustine. Wey Gómez draws a sustained contrast between the open geography of the Aristotelian model (which considered the known inhabited world to be only part of a larger world that might include additional landmasses) and the closed geography of the Christians (Augustine considered heretical the idea that humans might inhabit the unexplored quarters of the globe).

Through a detailed study of Columbus’s marginalia in the Tractatus of d’Ailly and Jean Gerson, Wey Gómez shows that Columbus accepted as valid the dimensions that d’Ailly gave for the Earth, which decreased the distance between Europe and Asia. Wey Gómez also uses the marginalia to demonstrate that Columbus did not believe that the torrid zone was entirely inhospitable to human habitation. Rather, he saw the equatorial regions of the globe as potentially replete with tremendous stores of wealth.

From The Tropics of Empire.

Later chapters reveal other geographical paradigms that may have influenced Columbus’s cosmological vision as well. Martín Fernández de Enciso’s Suma de geographia (1517), for instance, put Columbus’s discovery of the West Indies in the context of a larger Iberian expansion toward Ethiopia, the Maluccas and India, a landmass that was thought to be located in the same latitudinal spectrum as the Canary Islands and Cape Bojador and that was reputed to be fertile and abundant, according to early European historians of the Indian subcontinent.

Ever present are the conflicts between Portugal and Spain over which nation would claim Atlantic Africa and later the Indies as dominions for trade, commerce and expansion. Wey Gómez highlights the back-and-forth political wrangling between the two competing empires, the important role played by the numerous papal bulls issued by Alexander VI, and Columbus’s ritualistic “possession” of newfound lands in the name of the Crowns of Aragon and Castile.

The last two chapters turn toward the “vertical rendezvous” between the Iberian world and its tropical American counterparts. Wey Gómez analyzes Columbus’s Diario in light of evidence that his encounter with the torrid zone was dominated by representations of Cathay (the geopolitical region of northern China) and India, and their respective climatic and cultural differences.

Columbus’s articulation of the tropical environment of the lands he discovered was governed by two impulses in Wey Gómez’s view: the desire to create an Edenic narrative of an earthly paradise and an equally potent wish to portray the native peoples of the region as politically and morally inferior to inhabitants of the temperate zone. Both of these visions emerged from medieval understandings of the relationship between Cathay and India. Myths such as that of Prester John (an apocryphal Christian priest-king who supposedly ruled India) and diplomatic tales from Marco Polo’s account of the embassy to the dominions of the Great Khan influenced Columbus’s written account and helped him formulate the terms under which he agreed to carry out the voyage on behalf of Ferdinand and Isabel.

In the concluding chapter, Wey Gómez brings us back to Columbus’s first voyage in 1492 and attempts to recapitulate through the text of the Diario the geopolitical operations described in the preceding chapters. Attention is given both to the geographical circumstances of the famous first expedition and to the ethnography of the native peoples Columbus came across in the Caribbean.

For the magnitude of its ambition—both in terms of the breadth of its sources and the comprehensive nature of its analysis—The Tropics of Empire deserves to be read and studied by scholars in many fields, especially those who are interested in how ancient and medieval geographical conceptions markedly influenced the narrative and political impulses of the early modern age. The book’s larger ambition is to show that Columbus’s “geopolitical paradox”—proclaiming the torrid zone to be a terrestrial paradise even as he dealt with its inhabitants in the cruelest and most infantilizing of ways—served as a template for Europe’s troubled relationship with the global south. Although this latter argument is a tantalizing and in many ways a useful perspective, The Tropics of Empire is most convincing in its historicization of Columbus’s literary and geographical world, not necessarily in its prescriptive ability to chart a direct path from the Discoverer’s “southing” on his way to the Indies to the troubled relationships between present-day populations who inhabit either side of the equatorial divide. What is more, there were certainly navigational and political considerations that led Columbus toward a southerly trajectory as well, topics that are less emphasized due to Wey Gómez’s focus on the literary and cosmological backdrop to the voyages. Nevertheless, Wey Gómez’s wide-ranging study of an individual who left far more than his culture’s mark on an entire hemisphere merits our careful attention. Those who believed, following the Columbus quincentennial, that there was little left to say about a Genoese sailor’s extraordinary adventures overseas will now be convinced otherwise.

Neil Safier is assistant professor of history at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He is the author of Measuring the New World: Enlightenment Science and South America (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.