This Article From Issue

January-February 2006

Volume 94, Number 1

Page 73

DOI: 10.1511/2006.57.73

Charles Darwin, Geologist. Sandra Herbert. xxii + 485 pp. Cornell University Press, 2005. $39.95.

In February 1859, Charles Darwin received the Wollaston Medal, the highest honor bestowed by the Geological Society of London, in recognition of his scientific contributions to the field. He was ecstatic; he had reached the pinnacle of geology. Eight months later, in November 1859, he published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Forever after, Darwin would be famous as a biologist. Sandra Herbert sets out to explain how the two sides of his scientific life and work were related and why we should remember Darwin the geologist.

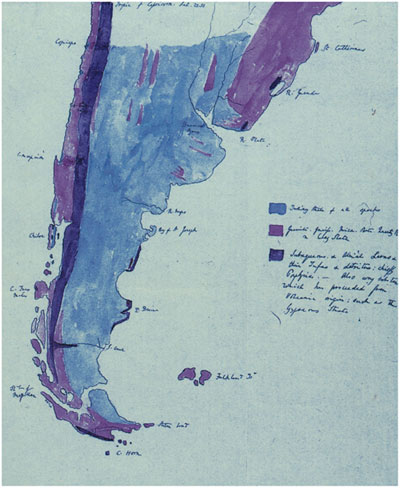

From Charles Darwin, Geologist

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) grew up with all the material advantages of a gentle-born Englishman. He also enjoyed certain "propitious circumstances," as Herbert describes them, that help to explain why a young man of means with an insatiable curiosity about the natural world would choose geology as his vocation. Europe was at peace following the devastating Napoleonic Wars, and Britain, the most prosperous and powerful country, ruled the waves. Scientific exploration was the order of the Admiralty, and so Darwin could hope to emulate the Pacific voyages of Captain James Cook. He also wanted to visit the tropics, as had Alexander von Humboldt, a naturalist whose method of exploration and style of writing influenced Darwin greatly. Like Humboldt, Darwin would combine physical and biological investigations.

Darwin's study of geology began at Edinburgh University, where his father sent him to study medicine in 1825. Darwin showed little interest in that profession and two years later "went up" to the University of Cambridge to prepare for the Anglican ministry. It was there under the mentorship of John Stevens Henslow, professor of mineralogy and later professor of botany, that Darwin learned how different were the theories of the Earth being taught at Edinburgh and Cambridge. As Herbert makes clear, geology in the 1820s and 1830s was a field full of big debates. This intellectual excitement and the chance to make a lasting contribution attracted the ambitious young Darwin. Such eagerness caught the attention of others at Cambridge, namely Adam Sedgwick, professor of geology. Sedgwick took Darwin to Wales in 1831, where he learned to do fieldwork and to feel joy in making scientific discoveries.

What made Darwin an active researcher, not simply a well-grounded student, was his round-the-world voyage aboard H.M.S. Beagle (1831-1836). Herbert recounts in colorful detail (both in words and pictures) the five years Darwin spent exploring South America and the islands of the Atlantic and Pacific. She also concentrates on what Darwin read during the voyage and thereby is able to show how Darwin observed, collected samples and interpreted these data in response to his growing knowledge and experience. This careful reconstruction displays Herbert's impressive mastery of all that Darwin wrote (letters, diaries, notebooks, publications) and all that has been written about him. Such comprehensiveness can, at times, leave a reader in a tangled bank of names and commentaries. Herbert calls her thick description and topical approach a "sinuous" history. Hence she picks up the three volumes of Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology (1830-1833) just as Darwin did during the voyage. In later chapters she returns to Lyell again and again as Darwin worked through his notes, wrote up his results and sharpened his ideas.

The voyage of the Beagle supplied Darwin with a lot more than specimens and observations—it gave him an identity. He became a scientific author. After his return to England, he published three books on geology and more than a dozen articles. In these works, he developed a grand theory of the Earth. Darwin tried to explain geological phenomena by the elevation and subsidence of the Earth's crust. Herbert refers to Darwin's research on the causes and consequences of vertical movements as "simple" geology. (Simple meant "having one mechanism or operation," not "unsophisticated.") This work marked Darwin as a bold theorist. It also put him outside the mainstream of geological research, which, as Herbert explains, focused on the identification, ordering and correlation of strata. Darwin was not so much interested in stratigraphy as he was in volcanoes, mountains and earthquakes. He was a structural theorist on a continental scale.

Darwin's most successful application of simple geology and his most lasting contribution to the science was his explanation of the origin of coral reefs. (They build up on the sides of slowly subsiding seamounts.) He then tried to apply his theory of vertical crustal movements to account for the parallel roads of Glen Roy, Scotland. This proved to be his decisive failure. Soon after he propounded his explanation, the roads were reinterpreted as remnants of glaciers. Ice, not the rise and fall of the crust, explained the phenomena. Darwin's grand theory of the Earth did not work, and for Herbert, this was a key factor in ending his active career as a geologist.

Another factor, of course, was evolution. By the early 1840s, Darwin was devoting his full energy to the species question. In developing his theory of natural selection, he had to work against an apparent lack of geological evidence; nowhere in the fossil record was there a clear example of the transmutation of one species into another. Herbert, too, has to work against an apparent lack of evidence; the connection between Darwin's geology and his biology is not obvious. Herbert, however, makes a strong case for reading deeper into the ways Darwin understood changes in time and changes in space. Rocks rise and sink; species appear and go extinct. What happens on one part of the globe is connected to another. Gradually, over long periods, small changes can accumulate into great effects. Continents will emerge, as do new animals and plants. For Herbert, what geology gave to Darwin was a gradualist's sense of time and a global perspective. For historians, what Herbert has presented is a broader view of the science of Charles Darwin.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.