High-Tech Homelessness

By Virginia Eubanks

Automated algorithms are designed to more efficiently match the unhoused with shelter, but such databases leave the poor vulnerable to privacy and rights breaches.

Automated algorithms are designed to more efficiently match the unhoused with shelter, but such databases leave the poor vulnerable to privacy and rights breaches.

Since the dawn of the digital age, decision-making in finance, employment, politics, health, and human services has undergone revolutionary change. Forty years ago, nearly all of the major decisions that shape our lives—whether or not we are offered employment, a mortgage, insurance, credit, or a government service—were made by human beings.

They often used actuarial processes that made them think more like computers than people, but human discretion still ruled the day. Today, we have ceded much of that decision-making power to sophisticated computer programs that control which neighborhoods get policed, which families attain needed resources, who is short-listed for employment, and who is investigated for fraud.

Mark Peterson/Redux

The skyrocketing economic insecurity of the past decade has been accompanied by an equally rapid rise of advanced data-based technologies in public services: predictive algorithms, risk models, and automated eligibility systems. Massive investments in data-driven administration of public programs are rationalized by a call for efficiency, doing more with less, and getting help to those who really need it.

I set out in 2014 to systematically investigate the impacts of high-tech sorting and monitoring systems on poor and working-class people in America. One system I studied, the electronic registry of the unhoused in Los Angeles, called the coordinated entry system, was piloted in 2013. It deploys computerized algorithms to match unhoused people in its registry to the most appropriate available housing resources. But its complex integrated databases store the most personal information from poor and working-class people, with few safeguards for privacy or data security, while offering almost nothing in return.

The software, algorithms, and models that power digital sorting are complex and often secret. And these systems are being integrated into human and social services across the country at a breathtaking pace, with little or no political discussion about their impacts. The coordinated entry system went from a privately funded pilot project in a single neighborhood to the government-supported front door for all homeless services in Los Angeles County—and its 10 million residents—in less than four years. Touted as the Match.com of homeless services, the coordinated entry approach has become wildly popular across the country in the past half decade. Its supporters include the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, the National Alliance to End Homelessness, a myriad of local homeless service providers, and powerful funders, including the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Once they scale up, digital systems can be remarkably hard to decommission. Once you break caseworkers’ duties into discrete and interchangeable tasks, install a ranking algorithm and a Homeless Management Information System, or integrate all your public service information in a data warehouse, it is nearly impossible to reverse course.

Although welfare recipients, the unhoused, and poor families face the heaviest burdens of high-tech scrutiny, they aren’t the only ones affected by the growth of automated decision-making. The most sweeping digital decision-making tools may be tested in what could be called “low rights environments” where there are few expectations of political accountability and transparency, but systems first designed for the poor will eventually be used on everyone.

The coordinated entry system was created to address the disastrous mismatch between housing supply and demand in Los Angeles County. Before coordinated entry, unhoused people navigated a complex system of wait-lists and social service programs requiring a great deal of patience, fortitude, and luck. Homeless service providers competed, both for limited funding and for rare available rooms for their clients.

Home for Good, a collaboration between the United Way of Greater Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce, launched a coordinated entry program in 2013. They pledged to house 100 of the most vulnerable homeless people in the Skid Row neighborhood in 100 days. To achieve this ambitious goal, they needed to create a complete list of Skid Row’s unhoused, ranked in order of need. They chose an assessment tool that collects vast amounts of information and sifts it for risky behaviors, built a digital registry to store the data, and designed two algorithms to rank the unhoused in order of vulnerability and to match them to housing opportunities.

The coordinated entry process begins when a social service worker or volunteer engages an unhoused person through an in-house service program, during a shelter admission, or as part of street outreach, using the Vulnerability Index—Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (VI-SPDAT). The survey includes incredibly intimate questions, including ones about sexual assault, mental health, sexual activity, and drug use.

The survey also collects protected personal information: social security number, full name, birth date, demographic information, veteran status, immigration and residency status, and where the respondent can be found at different times of day. The surveyor will ask if it is okay to take a photograph.

The consent form that the unhoused are asked to sign before taking the VI-SPDAT informs them that their information will be shared with “organizations [that] may include homeless service providers, other social service organizations, housing groups, and health-care providers,” and refers them to a fuller privacy notice that can be provided on request. If survey-takers request the more complete privacy notice, they learn that their information will be shared with 168 different organizations, including city governments, rescue missions, nonprofit housing developers, health-care providers, hospitals, religious organizations, addiction recovery centers, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Los Angeles Police Department “when required by law or for law enforcement purposes . . . to prevent a serious threat to health or safety.” The consent is valid for seven years.

After assessment, their data is entered into a federally approved Homeless Management Information System for the Los Angeles area and a ranking algorithm tallies up a score from 1 to 17. A 17 means the person surveyed is among the most vulnerable. Those scoring between 0 and 3 are judged to need no housing intervention. Those scoring between 4 and 7 qualify to be assessed for limited-term rental subsidies and some case management services—an intervention strategy called rapid rehousing. Those scoring 8 or above qualify to be assessed for permanent supportive housing.

Simultaneously, housing providers fill out vacancy forms to populate a list of available units. A second algorithm, the matching algorithm, is run to identify a person “who is in greatest need of that particular housing type (by virtue of their VI-SPDAT score)” and who “meets its specific eligibility criteria.”

If a successful match is made, the unhoused person is assigned a housing navigator, a special caseworker who helps gather all necessary eligibility documentation. A birth certificate, photo ID, social security card, income verification, and other documents must be collected in about three weeks. Once documents are in hand, the unhoused person fills out an application with the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, which then interviews the potential tenant, verifies their information and documentation, and approves or denies the application. If the application is approved, the unhoused person receives housing or related resources. If not, the match disappears and the algorithm is run again to produce a new applicant for the opportunity.

Using coordinated entry in the neighborhood of South Los Angeles is less like finding a date online and more like running an obstacle course. There is no guarantee that clients will find housing; vouchers expire after six months, and then the process starts all over again. For many unhoused people, the unfulfilled promise of coordinated entry has been demoralizing.

In the absence of sufficient public investment in building or repurposing housing, coordinated entry is a system for managing homelessness, not solving it. Chris Ko, architect of coordinated entry, agrees. “Coordinated entry is necessary but not sufficient,” he said. “It’s a tool to more efficiently use the resources fed into it. But we need permanent sources of subsidy.”

According to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority’s 2017 homeless count, there are 57,794 unhoused people in Los Angeles County. Since 2014, the homeless services community has managed to survey 31,124 individuals with the VI-SPDAT, which represent somewhere between 35 and 50 percent of the total homeless population, assuming that many people cycled between homelessness and housing in the intervening three years. Of those surveyed, coordinated entry has managed to connect 9,627 people with housing or housing-related resources. Ko estimates that coordinated entry has cost approximately $11 million so far, a total that includes only the cost of technical resources, software, and extra personnel, not the cost of providing actual housing or services. Thus the system eased the way to some kind of housing resource for 17 percent of the overall homeless population at a cost of approximately $1,140 per person. It is easy to argue that this is money well spent.

But it is impossible to know how many of the 9,627 people matched by coordinated entry received a place to call home, how many received assistance finding an apartment or a few hundred dollars to help with a rental deposit, and how many received assistance but have since become homeless again.

For the tens of thousands who have not been matched with any services, coordinated entry seems to have collected increasingly sensitive, intrusive data to track their movements and behavior, without offering anything in return.

Some suspect that all that data is being held for other purposes entirely: to surveil and criminalize the unhoused. As of this writing, the protected personal information of 21,500 of Los Angeles’ most vulnerable people remains in a database that may never connect them with life-saving services. It is possible to revoke your consent to be included, but the process is complicated. Even after expungement, some data stays in the system.

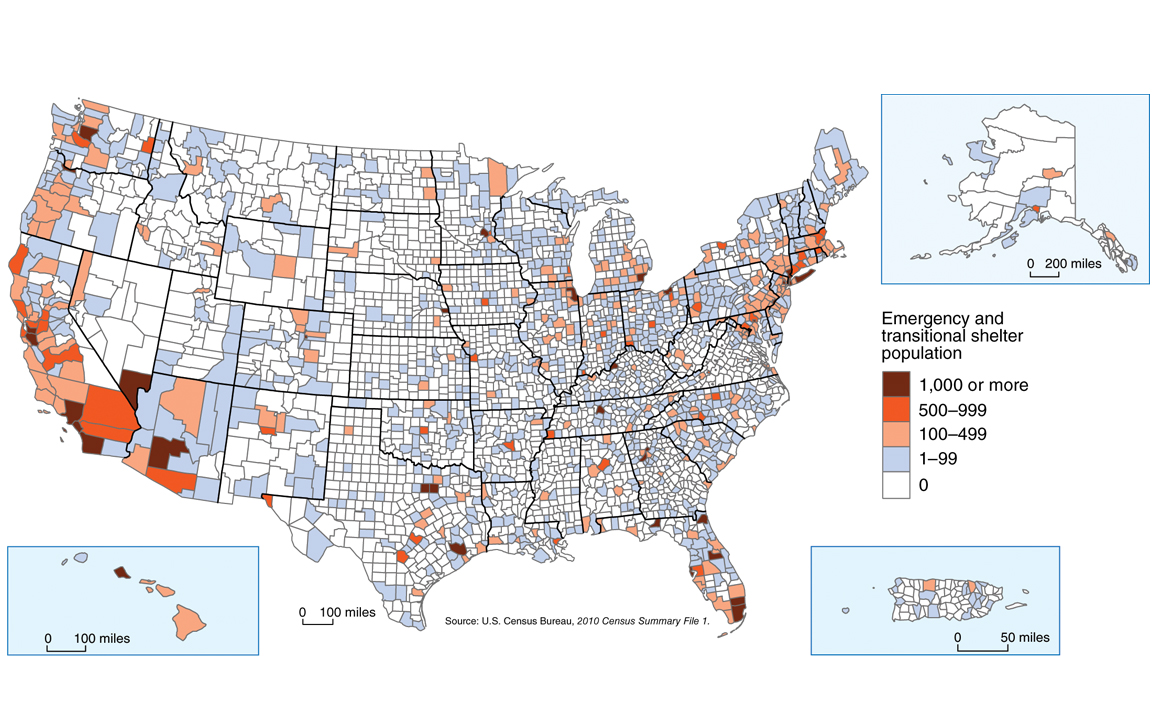

U.S. CENSUS BUREAU

Protected personal information is now collected by default; the system requires the unhoused to “opt in” to confidentiality. And there is virtually no other path to homeless services in Los Angeles County.

According to federal data standards, service providers may disclose protected personal information in the Homeless Management Information System to law enforcement “in response to . . . [an] oral request for the purpose of identifying or locating a suspect, fugitive, material witness or missing person.” The information that the LAPD can access is limited to name, address, date and place of birth, social security number, and distinguishing physical characteristics. But there is no mandatory review or approval process for oral requests. There is no requirement that the information released be limited in scope or specific to an ongoing case. There is no warrant process, no departmental oversight, no judge involved to make sure the request is constitutional.

Older analog systems of surveillance required individualized attention: The target had to be identified before the watcher could surveil. In contrast, in new data-based surveillance, the targeting comes after the data collection, not before. Massive amounts of information are collected on a wide variety of individuals and groups. Then, the data is mined to identify possible targets for more thorough scrutiny.

And many of the basic conditions of being homeless—having nowhere to sleep, nowhere to put your stuff, and nowhere to go to the bathroom—are also officially crimes. If sleeping in a public park, leaving your possessions on the sidewalk, or urinating in a stairwell are met with a ticket, the great majority of the unhoused have no way to pay resulting fines. The tickets turn into warrants, and then law enforcement has further reason to search the databases to find “fugitives.”

Proponents of the coordinated entry system, like many who seek to harness computational power for social justice, tend to find affinity with systems engineering approaches to social problems. These perspectives assume that complex controversies can be solved by getting correct information where it needs to go as efficiently as possible. In this model, political conflict arises primarily from a lack of information. If we just gather all the facts, systems engineers assume, the correct answers to intractable policy problems such as homelessness will be simple, uncontroversial, and widely shared.

But, for better or worse, this is not how politics works. Political contests are more than informational. They are about values, group membership, and balancing conflicting interests. Having more information won’t necessarily resolve them.

The faith that faster, more accurate data will succeed in building the housing Los Angeles needs may be naive. And as the perception of increased resources for the homeless rises, the city’s fragile tolerance for homeless encampments may unravel. Los Angeles voters recently committed to pay a bit more in sales and property taxes in order to house the homeless. But will the housed let the homeless move into their neighborhoods? Evidence suggests that building new low-income housing or repurposing older buildings to house the homeless will prove challenging. Two recent proposals to build storage units for the unhoused’s belongings erupted into community-wide protest.

Systems engineering can help manage big, complex social problems. But it doesn’t build houses, and it may not prove sufficient to overcome deep-seated prejudice against the poor, especially poor people of color. Although coordinated entry may minimize some of the implicit bias of individual homeless service providers, that doesn’t mean it is a good idea, says public interest lawyer, homeless advocate, and emeritus professor of law at UCLA Gary Blasi. “My objection to [coordinated entry] is that it has drawn resources and attention from other aspects of the problem. For 30 years, I’ve seen this notion, especially among well-educated people, that it’s just a question of information. Homeless people just don’t have the information.”

“Fraud is too strong a word,” said Blasi. “But homelessness is not a systems engineering problem. It’s a carpentry problem.”

When we talk about the technologies that mediate our interactions with public agencies today, we tend to focus on their innovative qualities, the ways they break with convention. Their biggest fans call them disruptors, arguing that they shake up old relations of power, producing government that is more transparent, responsive, efficient, even inherently more democratic.

This myopic focus on what’s new leads us to miss the important ways in which digital tools are embedded in old systems of power and privilege.

According to its designers, the county’s coordinated entry system matches the greatest need to the most appropriate resource. But there is another way to see the ranking function of the coordinated entry system: as a cost-benefit analysis. It is cheaper to provide the most vulnerable, chronically unhoused with permanent supportive housing than it is to leave them to emergency rooms, mental health facilities, and prisons. It is cheaper to provide the least vulnerable unhoused with the small, time-limited investments of rapid rehousing than to let them become chronically homeless. This social sorting works out well for those at the top and the bottom of the rankings. But if the cost of your survival exceeds potential taxpayer savings, your life is deprioritized.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The data collected by coordinated entry also creates a new story about homelessness in Los Angeles. This story can develop in one of two ways. In the optimistic version, more nuanced data helps the county, and the nation, face its cataclysmic failure to care for our unhoused neighbors. In the pessimistic version, the very act of classifying homeless individuals on a scale of vulnerability erodes public support for the unhoused as a group. It leaves professional middle-class people with the impression that those who are truly in need are getting help, and that those who fail to secure resources are fundamentally unmanageable or criminal.

At lectures, conferences, and gatherings, I am often approached by engineers or data scientists who want to talk about the economic and social implications of their designs. I tell them to do a quick “gut check” by answering two questions: Does the tool increase the self-determination and agency of the poor? And would the tool be tolerated if it was targeted at nonpoor people?

As we create a new national narrative and politics of poverty, we must also begin asking entirely different kinds of questions: How would a data-based system work if it was meant to encourage poor and working-class people to use resources to meet their needs in their own ways? What would decision-making systems that see poor people, families, and neighborhoods as infinitely valuable and innovative look like? It will also require sharpening our skills: High-tech tools that protect human rights and strengthen human capacity are more difficult to build than those that do not.

Digital surveillance infrastructure offers a degree of control unrivaled in history. Automated tools for classifying the poor, left on their own, will produce towering inequalities unless we make an explicit commitment to forge another path. And yet we act as if justice will take care of itself.

This article is excerpted and adapted from Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. Copyright 2018 by Virginia Eubanks, and reprinted with permission from St. Martin’s Press.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.