Science Book Gift Guide 2019

By The Editors

STEM-related books for this or any season

December 11, 2019

Science Culture Art Astronomy Biology Chemistry Environment Review Scientists Nightstand

For this holiday season and beyond, we’ve selected some books that will appeal to science enthusiasts young and old. Have a look below at some of the books we’ve enjoyed this year, and come back to this page soon, as we’ll continue to add to this list in the days leading up to Christmas. Happy holidays!

Jump to: STEM Books for Adults

STEM Books for Young Readers

(Suggested age ranges, where noted, are those provided by the publisher.)

Look and Learn Nature Detective (PBS KIDS) by Sarah Parvis. Downtown Bookworks, 2019. $19.99. Ages 4 and up.

A great gift option for preschool and elementary school children is Look and Learn Nature Detective, from PBS KIDS. The book comes in a box that includes a magnifying glass, which makes for a more substantial gift. Its 64 colorful pages feature numerous informative photographs, large type that’s easy to read, and accessible language; the last page includes a pronunciation guide for several words that may be unfamiliar to young readers, such as deciduous. The author encourages kids to use their senses and points them toward often-overlooked areas for exploration: Crouch down to discover animal tracks in the mud, she advises; shake an acorn and listen for the rattle that indicates an insect has been munching on it; use the magnifying glass to study insect bite marks on leaves. This emphasis on everyday nature makes it possible for kids in any environment to participate in the activities; if they can’t go to the forest to examine pinecones, perhaps they can study a spider web inside an apartment. When I brought this book home, my six-year-old was so excited he nearly ripped it from my hands, and my two-year-old enjoyed looking at the beautiful photographs of magnified plants and animals. The next time I go out with the boys, I plan to slip this slim little book into my bag to add some excitement to our excursion.—Stacey Lutkoski

A Kite for Moon by Jane Yolen and Heidi E. Y. Stemple, illustrated by Matt Phelan. Zonderkids, 2019. $18.

A common theme in children’s books is the transformation of dreams into reality. A Kite for Moon tweaks this theme by emphasizing the importance of inspiration and hard work in achieving your goals. The book, which is dedicated to Neil Armstrong, follows a boy who imagines that the Moon is lonely, so he sends up a kite to keep it company. As the years go by, the boy continues to watch the Moon with an increasingly academic intensity. Beautiful watercolor paintings depict him surrounded by books, peering through a telescope and then a microscope. Simple, sparse words outline the progression of his knowledge and skills as he moves from doing small sums to studying algebra and geometry, and from riding a bicycle to driving a car to flying a plane and then a rocket. As an adult he becomes an astronaut and visits the Moon, greeting it as an old friend.—Stacey Lutkoski

Ollie and Harry’s Marvelous Adventures , by Ollie Ferguson and Harry Ferguson. Norton Young Readers, 2019. $19.95.

Scottish brothers Ollie (age 10) and Harry (age 7) Ferguson have made a list of 500 adventures they aim to complete before they turn 18, and they are already more than halfway through the list. Their parents document their exploits on Facebook, and now a book that describes some of their projects is available: Ollie and Harry’s Marvelous Adventures. The book provides detailed instructions on how to do a wide variety of things, from building a fire without matches to sending Lego figures into near space, more than 20 miles above the Earth. Although Harry and Ollie have done much of the work on these projects themselves, most of the adventures in the book require considerable adult supervision and assistance. And many of the projects aren’t cheap: Creating a homemade spacecraft that can carry Legos into near space requires specialized equipment (a high-altitude balloon and a parachute); to document the trip, you’ll need a GoPro or other camera, and to have any chance of retrieving items afterward, you’ll need a GPS locator. (You’ll also need to get permission to make the flight from aviation authorities.) But many of their projects are easy to carry out with items found around the house—for example, construction of a film projector for outdoor movie nights requires only a shoebox, a magnifying glass, and a smartphone. Even the less accessible adventures are fun to read about, and the breadth of topics the boys tackle is impressive. Giving this book to kids with active imaginations will show them that even crazily ambitious ideas can be carried out. But beware: You may soon find yourself helping a child to mummify a fish.—Stacey Lutkoski

Moon! Earth’s Best Friend, by Stacy McAnulty; illustrated by Stevie Lewis. Henry Holt and Company, Holt Books for Young Readers, 2019. $17.99. Ages 4 to 8.

“I didn’t know that,” gasped my 10-year-old niece, who was listening in as I read this bedtime book to her six-year-old brother. Moon! Earth’s Best Friend is full of facts about Earth’s “#1 sidekick,” as told by Moon herself. The fact that had made my niece gasp was the information that the Moon is “the only other place in the universe where man has set foot.” Younger kids (and apparently their somewhat older siblings as well) will find the book’s fun tone and creative illustration style engaging. Words such as satellite and gravity are defined in the pages, so the text will be over the heads of toddlers, but the colorful nighttime pictures of eclipses, tides, and the footprints and objects astronauts left behind on the Moon will appeal to all ages.—Katie L. Burke

The Very Impatient Caterpillar, by Ross Burach. Scholastic Press, 2019. $17.99. Ages 4 to 8.

Lots of people have heard of the Very Hungry Caterpillar, but the very impatient caterpillar is much sillier. He annoys all the other caterpillars and cocooned ones in transition by repeatedly asking questions like, “Am I a butterfly yet?” He is so very excited, but he has to wait and wait for nature to take its course. What can he do to fill the “TWO WEEKS?!” it will take him to transform? And then, once he does become a butterfly, he finds out there are more challenges ahead: Migration is next, and he immediately begins yelling, “ARE WE THERE YET?!”—Katie L. Burke

The Big Sticker Book of Birds, by Yuval Zommer. Thames and Hudson, 2019. $14.95. Ages 5 and up.

This book makes learning about the great diversity of the world’s birds interactive. It includes beautiful illustrations and more than 200 stickers. But stickers aren’t the only thing kids will need to play along: A pencil, coloring utensils, and a “flighty imagination” are also essential. Suggested activities described in the text include matching parent birds with their babies, designing camouflage patterns for eggs, playing Blackbird Bingo, and designing a crown for a hoopoe. As children follow the book’s instructions, they will learn the names of different birds and something about their natural history.—Katie L. Burke

The Raptors of North America: A Coloring Book of Eagles, Hawks, Falcons, and Owls, by Anne Price, with illustrations by Donald Malick. University of New Mexico Press, 2019. $14.95. For readers of middle-school age.

The author of this beautiful educational coloring book is an avid falconer and the curator of the Raptor Education Foundation in Colorado, which receives proceeds from sales of the book. Introductory material suggests how to use the book with young people of different ages and covers such topics as the descent of raptors from dinosaurs, what makes a bird a raptor, scientific names, and threats to raptor populations. By coloring in the book’s intricate line drawings, using the accompanying watercolor illustrations as a guide, beginning birders will learn the visual details that set apart the 52 different species of raptors portrayed. Each illustration is accompanied by a paragraph of text introducing the bird, along with a “cool fact” box that states something distinctive and memorable about the species. The coloring portion of the book is followed by material that dives into the history of falconry, explains how to build a nest box for kestrels, and asks you to match photos of feathers, eggs, and feet. Useful items at the back of the book include a glossary, a bibliography, and a checklist of raptors you’ve seen.—Katie L. Burke

The Year We Fell from Space, by Amy Sarig King. Arthur A. Levine Books (an imprint of Scholastic), 2019. $16.99; also available as an audiobook for $20.99. Ages 8 to 12.

This work of fiction tells the story of a family going through a divorce, from the perspective of a 12-year-old girl, Liberty Johansen. Liberty is no ordinary girl. She loves drawing star maps that show the new constellations that she invents, and she is set on changing the way people see the night sky. She wants them to abandon the old constellations, find their own patterns, and draw their own maps. Using lines to connect dots of starlight in the sky helps her figure out her feelings, Liberty says. Can she also map a new life with new patterns for her family after her father moves out? King’s writing draws on beautiful metaphors, relatable character dilemmas, character development, and magical realism to help young readers process challenging family issues, such as a parent’s depression or a parent dating someone new. Few books for young people tackle such deep and tender issues. King explores complicated emotions in depth, affirming that kids feel them and need to acknowledge and move through them.—Katie L. Burke

Reaching for the Moon: The Autobiography of NASA Mathematician Katherine Johnson, by Katherine Johnson. Simon and Schuster Children’s Publishing Division, 2019. $17.99. Ages 10 and up.

In this autobiography, NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson tells her story. It’s a story that was made famous by the movie Hidden Figures and the 2016 book by Margot Lee Shetterly on which the movie is based. In Reaching for the Moon, Johnson weaves together African-American history with the history of science as she describes what it was like to be a black, intellectual, math whiz attending segregated schools. The autobiography is written at a level accessible to readers as young as 10 years, but I think adults will also enjoy hearing about what Johnson has thought and experienced over the course of her long, incredible life. She was born in 1918 and is still living. She had to deal with segregation in Virginia and West Virginia in the Roaring Twenties and later while coping with the hardships of the Great Depression and World War II. Then she raised three daughters during the Civil Rights Movement while working as a mathematician on the development of spacecraft at NASA. Undaunted by the racism and sexism she encounters, throughout the book she repeats the mantra her father taught her: “You are no better than anyone else, and nobody else is better than you.”—Katie L. Burke

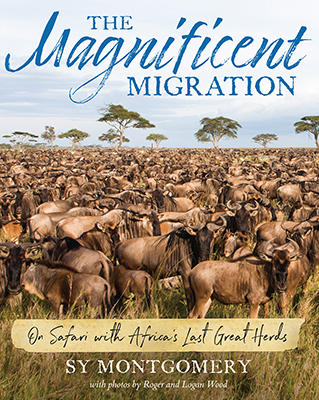

The Magnificent Migration: On Safari with Africa’s Last Great Herds, by Sy Montgomery, with photos by Roger and Logan Wood. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019. Cloth, $24.99; eBook, $12.99. Ages 10 and up.

The Magnificent Migration is a lively account of going on safari with Richard Despard Estes, the world’s top expert on wildebeests (gnus). Award-winning author Sy Montgomery and four other fans of Estes are accompanying him as he tracks the migration of wildebeests across the Serengeti; more than a million of these African antelopes follow the rains year-round, searching for grass in herds of tens of thousands, taking a clockwise 800-mile route. Hundreds of thousands of zebras and gazelles travel alongside, making the migration the largest known movement of animals on land. This force of nature affects everything in its path: land, water, plants, predators, and prey. Across 11 chapters, Montgomery describes everything the group experiences on safari, including the logistics of travel, such as campsites and vehicles that break down, as well as the sights they see and interesting species they come across, including lions, hyenas, cheetahs, giraffes, hyraxes, and dik-diks. The chapters all have sidebars, some of which focus on migration in other species, including the Arctic tern, sardines, loggerhead sea turtles, monarch butterflies, and zooplankton. Additional sidebar topics include tsetse flies, poachers’ snares, and fire in the Serengeti. The book’s dozens of excellent color photographs of the savanna and its inhabitants, taken by group members Roger and Logan Wood, will likely inspire in readers the same “tenderness toward this great landscape” that Montgomery feels. On her way home, she reflects on the fate of the Serengeti, “this last of the world’s remaining great savanna ecosystems,” noting that it has lost 40 percent of the area it encompassed in 1900.—Flora Taylor

Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World’s Greatest Nuclear Disaster, by Adam Higginbotham. Simon and Schuster, 2019. Cloth $29.95; paper $19.

If you’re searching for a gift for someone who loves thrillers, Midnight in Chernobyl fits the bill. Like Serhii Plokhy’s Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe (reviewed in the July-August 2018 issue), Adam Higginbotham’s book opens with a dramatic reconstruction of the disaster at the nuclear plant. This vivid blow-by-blow account of the events leading up to the explosion is impossible to put down, even if you’re familiar with what happened from having viewed the HBO miniseries about Chernobyl. Midnight in Chernobyl is much more comprehensive and detailed than the miniseries and has a larger cast of characters. Higginbotham has done extensive research and reporting, conducting hundreds of hours of interviews in Ukraine over a period of 10 years.

The book’s descriptions of the frantic attempts to cope with the immediate aftermath of the explosion and contain the disaster are gripping. There are heroes and villains aplenty: A number of people displayed great bravery, and some sacrificed their lives (in some cases unwittingly). Bureaucratic incompetence was much on display, and the primary goal of many officials was to cover up what had happened at any cost. Yet the characters are so sharply drawn, and the context in which they were operating is delineated so clearly, that you may find yourself empathizing even with the hapless bureaucrats.

Higginbotham brings the story of Chernobyl almost to the present day, ending his account with the dedication in 2016 of the New Safe Confinement structure put in place then over the reactor core and associated wreckage, covering the older, deteriorating sarcophagus. “Safe confinement” notwithstanding, guests at the dedication were handed lanyards with dosimetry buttons on arrival. And the story is far from over: The new structure confining the radiation is designed to last for only 100 years.—Flora Taylor

Moonfire: The Epic Journey of Apollo 11, 50th Anniversary Edition, by Norman Mailer. Taschen, 2019. $50.

Back in June, when we posted on this blog reviews of this year’s bumper crop of moon-landing books (which would themselves make excellent gifts), Moonfire: The Epic Journey of Apollo 11 wasn’t included because it hadn’t yet been published. It’s both lavish and massive (345 oversize pages), with roughly 400 or so photographs, about half of which are in color; some are familiar, but quite a few are not. The text is excerpted from a book by Norman Mailer published in 1971 under the title Of a Fire on the Moon; that book grew out of a very long article that Life magazine had commissioned Mailer to write in 1969.

From Moonfire. © NASA/Courtesy of TASCHEN

The book’s photos are terrific, but from the point of view of readers interested in Apollo 11 rather than Mailer, the text could have used a heavy edit. It contains some interesting information, but to ferret it out, you have to wade through a lot of digressive verbiage. For example, more than 30 pages of text are devoted to Mailer’s internal stream of consciousness during the time he spent at the Texas mansion of wealthy Europeans who had invited him over to watch the ascent of the Lunar Module from Tranquility Base to the spacecraft Columbia.

Mailer, who throughout the book refers to himself in the third person as a reporter named Aquarius, says of the Moon landing, “It was the event of his lifetime, and yet it had been a dull event.” It’s actually the tiresomely egocentric portions of Mailer’s text that readers are likely to find dull. (Do we really need to know, for instance, that “Aquarius on evenings like this would look for the nutrient in liquor the way a hound needles out marrow from a bone”?)

Nevertheless, the splendid photos documenting the journey of Apollo 11 make this a first-rate coffee-table book.—Flora Taylor

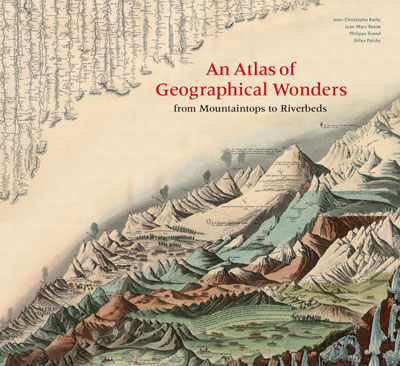

An Atlas of Geographical Wonders from Mountaintops to Riverbeds: A Selection of Comparative Maps and Tableaux, by Jean-Christophe Bailly, Jean-Marc Besse, Philippe Grand, and Gilles Palsky. Princeton Architectural Press, 2019. $50.

A few hundred years ago, no one on Earth could have told you what the tallest mountain is, or the longest river. It was only around 1800 that European adventurers and naturalists started making scientific expeditions to collect the necessary facts and figures to make these sorts of global comparisons. In the following decades creative techniques for visualizing all this data flowered. For example, artists and printers devised tableaux that brought together the world’s highest mountains, arranging them shoulder-to-shoulder in one spiky range of peaks and ridges. And they straightened out all the rivers, making them flow parallel for ease of comparison.

An Atlas of Geographical Wonders collects dozens of these graphics, lusciously presented on large-format pages and heavyweight paper. Some of the figures are highly schematic, but others are richly pictorial, creating a fictional landscape in which the Alps and the Andes become the foothills of the Himalayas. Brief introductory essays by the editors explain the origin and the evolution of the genre. I wish that there were also a concluding essay looking back from the age of Google Maps and satellite geodesy on these early attempts to comprehend the entirety of the planet.

From An Atlas of Geographical Wonders.

My favorite image in the collection is a watercolor sketch (see image above) by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, which he based on preliminary reports from Alexander von Humboldt’s explorations. The painting juxtaposes some of the highest peaks in Europe (on the left) with those of South America. At the left margin, standing atop Mont Blanc is the naturalist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, and at far right, von Humboldt waves from the slopes of the Ecuadoran volcano Chimborazo. Overhead is a hot-air balloon known to have reached an altitude of more than 6,000 meters, and in the lower right corner, at sea level, is a crocodile, perhaps an ironic echo of the monsters that occupied terra incognita on earlier maps.—Brian Hayes

Change Is the Only Constant: The Wisdom of Calculus in a Madcap World, by Ben Orlin, Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2019. $27.99.

Change Is the Only Constant is a follow-up to Ben Orlin’s previous book, Math with Bad Drawings (reviewed here). In this book, a particular branch of mathematics—calculus—is the protagonist. Having taught calculus myself at both the high school and college levels, I was curious about how this famed math blogger would handle a subject I know and love so well. As Orlin makes clear from the beginning, readers won’t learn calculus from the book; rather, they will learn in a “storybook” manner (with Orlin's characteristically bad drawings) about the two main tools of calculus, derivatives and integrals. Orlin broadly characterizes these two tools as Moments (derivatives), which are discussed in the first half of the book, and as Eternities (integrals), which are covered in the second half. And it’s through those Moments and Eternities that Orlin connects the big thoughts in philosophy, history, and economics, among other fields, with those in calculus. Orlin is not starry-eyed, though, about the application of calculus to these other fields. For example, he notes that Leo Tolstoy, author of War and Peace, used calculus only as a metaphor to describe history as being, in some sense, the sum of "infinitesimally small elements by which the masses [of people] are moved,” but sees no claim that there is a way to describe history (and so predict the future) with some calculus-based formula still to be discovered. So, in sum—ahem!—people who never made it through calculus (or, at least those who still talk about how they wished they had) will appreciate Orlin’s book. So too will calculus teachers and students, particularly with the “classroom notes” section at the end that helpfully pairs Orlin’s delightfully written chapters with the traditional calculus curriculum.—Robert Frederick

The Art of the Bird: The History of Ornithological Art through Forty Artists, by Roger J. Lederer. University of Chicago Press, Carlton Publishing Group, 2019. $35.

Art history and the history of science intertwine in this beautiful tribute to the scientific illustration of birds. Although people have been depicting birds since Paleolithic times, in The Art of the Bird, ecologist and ornithologist Roger J. Lederer is celebrating the contributions of illustrators to natural history and science, starting in the 1500s. The book begins with a brief overview of bird illustration as seen through the lenses of the cultural symbolism of birds and the technological history of imaging and art. The rest of the book is divided into sections based on major periods in the history of art and science, with subsections devoted to each prominent artist of the period. The book notes the contributions of major figures such as Alexander Wilson, John James Audubon, and Roger Tory Peterson to natural history and the environmental movement. Changes in bird illustration over time reflect developments in ecology, natural history, and environmental philosophy. For example, during the Renaissance, paintings of birds did not include any environmental context, but as the importance of habitat for identifying and conserving them became apparent, conventions changed, and birds began to be depicted in their natural surroundings. Most of the artists featured are European men or men of European descent; as Lederer acknowledges, this lack of diversity is a reflection of the racism, colonialism, and sexism that have existed as science has developed as a practice and profession. The first woman artist featured in this book is Lady Elizabeth Symonds Gwillim (1763–1807), and the first featured artist of Latin American descent is Louis Agassiz Fuertes (1874–1927), an American of Puerto Rican descent. I found myself wondering what sorts of contributions may have been made by people who go unmentioned in the book, including the enslaved, colonized peoples, and their descendants.—Katie L. Burke

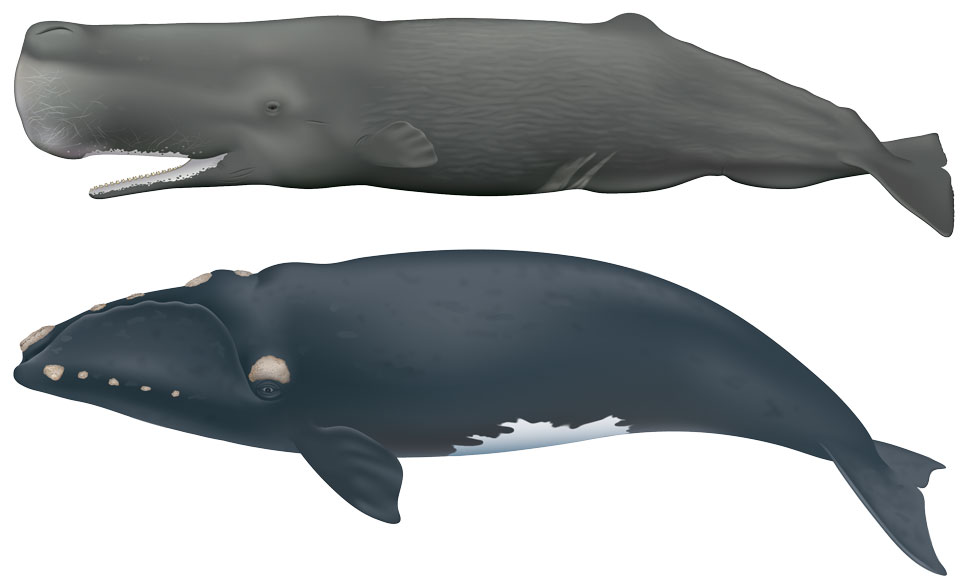

Ahab’s Rolling Sea: A Natural History of Moby-Dick, by Richard J. King. University of Chicago Press, 2019. $30.

This examination of Moby-Dick as nature writing could be a sneaky way to get the English majors on your shopping list to read about science. In Ahab’s Rolling Sea, Richard J. King uses Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick to gauge American knowledge and views of the ocean and its inhabitants in the mid-19th century and to consider how those views have changed over the intervening 170 or so years. King follows the voyage of the Pequod, exploring topics in marine biology, oceanography, and navigation as Ishmael (Melville’s narrator) takes them up; these topics range from whale migration, physiology, intelligence, and behavior (including aggression) to phosphorescence, sharks, coral insects, typhoons, and St. Elmo’s Fire.

From a chart in Moby-Dick that is reproduced in Ahab’s Rolling Sea.

King, who teaches maritime literature and history and has spent time on sailing ships in the Pacific, begins by briefly considering Melville as a whaleman, author, and natural philosopher, and then lists the books on natural history at Melville’s disposal, which included Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle. As King moves through the subject matter discussed by Ishmael, he uses interviews with marine biologists and other experts to bring the reader up to date on such topics as whale taxonomy.

In the final chapter of Ahab’s Rolling Sea, King argues that Moby-Dick is “proto-Darwinian” and “proto-environmentalist.” With its themes of hubris and relentless pursuit, he says, the novel is “a blue fable that decenters man, revealing how messing with the forces of the natural ocean world will end poorly for humans.”—Flora Taylor

Consider the Platypus: Evolution through Biology’s Most Baffling Beasts, by Maggie Ryan Sandford; illustrated by Rodica Prato. Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, Running Press, 2019. $15.99.

Consider the Platypus is a marvelously fun book, one that encourages the reader to think about evolution from new angles by exploring the “oddballs of the animal kingdom,” who are some of the favorite animals of evolutionary biologists. The book divides animals into four groups: those that look strange, such as the platypus and the blue whale, and were therefore scrutinized by early evolutionary biologists; those that have lent insight into how humans evolved, such as the fruit fly and the Great Barrier Reef demosponge; those that possess a “‘monstrous’ adaptation that seems more trouble than it is worth,” such as the aye-aye and the Galapagos tortoise; and those that push the boundaries of longevity, such as the axolotl and the tardigrade. Several pages of background information are provided for each animal; included are lovely ink-and-watercolor illustrations by Rodica Prato, a “Fam-O-Meter” score that divulges how much genetic material the animal shares with humans, a “Beastly Breakdown” covering its form and function, and a “lesson” about evolution proffered by the animal. The first section of animals includes those that evolutionary biologists have used to scrutinize Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Also, many animals throughout the sections are accompanied by sidebars titled “Through Darwin’s Eyes”; these sidebars discuss how the eminent biologist thought about that animal or its taxonomic group. As Sandford says of evolution, “Monkeys ain’t even half of it.”—Katie L. Burke

Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution, by Beth Gardiner. University of Chicago Press, 2019. $27.50.

This comprehensive book on air pollution covers the globe, focusing on the most polluted places in the world (Delhi, London, Los Angeles, Beijing) and discussing the people who have made history by putting in place policies and technologies that address this enormous problem, such as the Clean Air Act; the catalytic converter; Chai Jing’s smog film Under the Dome; and China’s 2013 action plan to reduce air pollution and coal use. Journalist Beth Gardiner is on a quest to find the people who are most effectively developing and implementing solutions; she wants to create a roadmap for humanity. The effects of air pollution are somewhat hidden: We know that it is one of the top global killers, but to determine whether it caused any particular individual’s death is very challenging. Gardiner writes, “This is a book about choices. About how we choose the kind of world we want to live in. And about the complexities of an age in which the things that have changed our lives for the better also bring consequences that are harder to see.” That our desire to make our lives better may be leading to a tragic outcome of epic proportions is a theme throughout the book, but Gardiner provides balance by emphasizing that “a different future is within our grasp.”—Katie L. Burke

Curious Creatures on Our Shores, by Chris Thorogood. The Bodleian Library in association with the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, 2019. $25.

This short (128-page) book contains 56 gorgeous color reproductions of oil paintings by the author portraying creatures that can be found at low tide along the shoreline of the British Isles (and in many cases along shorelines elsewhere as well). The first quarter of the book offers brief illustrated descriptions of groups of animals: sponges; jellyfish, anemones, and corals; Bristle worms; crabs and lobsters; snails, clams, slugs, octopuses, and squid; starfish, urchins, and sea cucumbers; and sea squirts.

From Curious Creatures on Our Shores.

The remainder of the book contains more detailed descriptions of specific habitats—the strand line, the shingle shore, the rocky shore, the sandy shore, and the open ocean—and the creatures biologically suited to each. At the strand line, for example, one finds jellyfish, the eggs of whelks and cuttlefish, the egg cases of sharks and rays (see image above), and rarely, the uncommon goose foot starfish.—Flora Taylor

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.