This Article From Issue

March-April 2026

Volume 114, Number 2

Page 120

STRATA: Stories from Deep Time. Laura Poppick. 288 pp. W. W. Norton, 2025. $29.99.

In Strata: Stories from Deep Time, science journalist Laura Poppick offers a compelling and scientifically grounded narrative that traces the planet’s most consequential transitions as recorded in its lithological archive. Poppick strikes a rare and commendable balance: She delivers accurate geoscientific content in prose that is lucid and engaging, without oversimplifying the complexity of Earth systems or the methods geologists use to decode them.

The book is organized thematically around four global-scale transformations that are both stratigraphically prominent and conceptually essential for understanding Earth’s evolution over the past two billion years: the Great Oxidation Event, when free oxygen first accumulated in the atmosphere; the global-scale Neoproterozoic glaciations (also called Snowball Earth); the colonization of land and the resulting changes in terrestrial sedimentation; and the Mesozoic greenhouse world, a period of sustained global warmth as expressed through dinosaur-bearing strata.

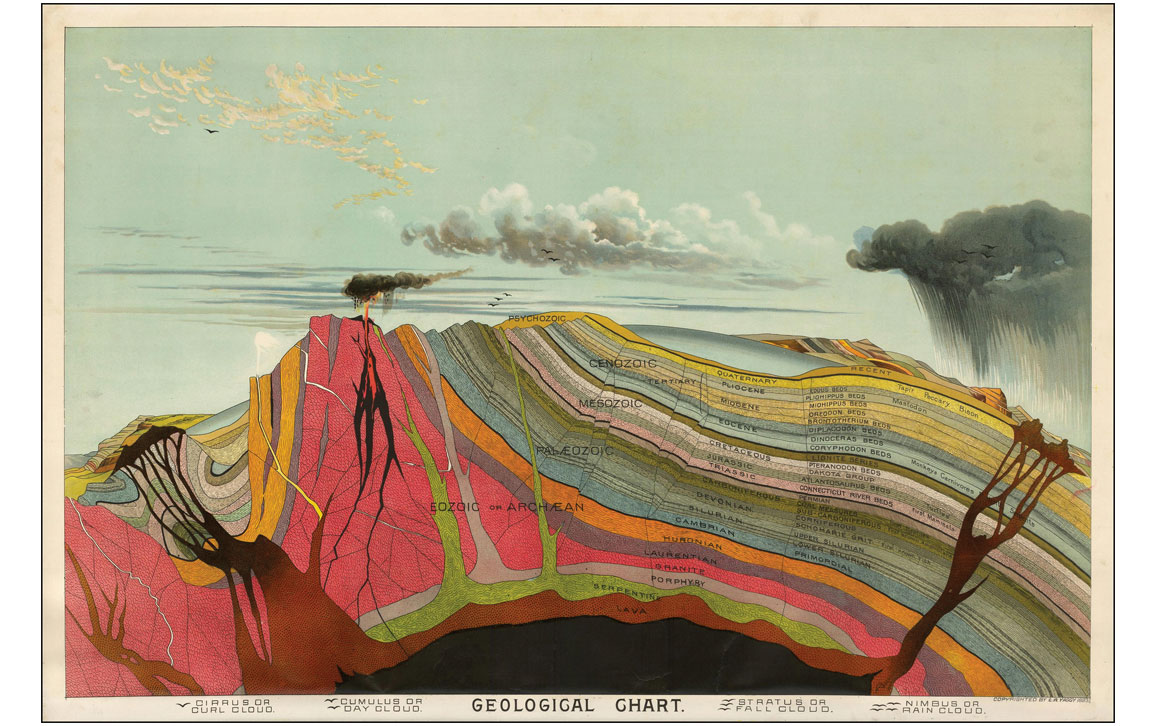

raremaps.com

Each of these four transformations is presented through two types of evidence: stratigraphic evidence (relating to the layers of rock and soil, or strata, that record Earth’s history over time) and sedimentological evidence (relating to the study of sediments such as sand, silt, and clay, and the processes that deposit them). Poppick highlights not just the major events in deep time but also the scientific techniques used to read Earth’s lithified memory. Through field-based profiles of contemporary researchers, Strata illustrates how geologists trace patterns in strata and sediments to reconstruct ancient environments and the forces that shaped them.

The book offers a subtle but consistent theme: that all of Earth’s geophysical systems are interlinked. Poppick presents our lithosphere, biosphere, atmosphere, and hydrosphere together as a complex, dynamic system that has evolved over billions of years. The result is a portrait of Earth as both resilient and contingent—a planet capable of self-stabilizing feedbacks, but also vulnerable to perturbations like the ones that produced the four great transformations.

Each section of the book effectively combines site-specific fieldwork with historical and contemporary geoscience research. For example, the chapter on the Great Oxidation Event takes readers into the Mesabi Range of Minnesota, where banded iron formations (BIFs) serve as mineralogical proxies for changing atmospheric chemistry. Poppick explains how redox-sensitive (reduction-oxidation sensitive) iron precipitated out of anoxic oceans as free oxygen began to accumulate, creating the iron oxide layers that now form the economic backbone of United States iron ore mining.

Poppick excels at describing the sheer scale and power of geologic processes across deep time. She writes,

The walls of Wyoming’s Bighorn Canyon rise above a slender lake that once ran as a river. That river flowed for many thousands of years, surging at the end of the last ice age as melting glaciers sent torrents down the Rocky Mountains and out into tributaries that carved through the earth like blades through soft lumber.

Her evocative language conveys both the microbial and geochemical processes at work and the way geologists interpret these records, making complex science tangible for readers.

For the Snowball Earth events, roughly 720 to 635 million years ago, Poppick takes us to the Flinders Ranges of South Australia, where glaciers once dotted the land. Dropstones, rocks dropped into finely layered shales by melting ice, now stand as frozen witnesses to a planet nearly locked in ice. As Poppick observes, “These stones, embedded in layers of ancient mud, are silent testaments to a world where life had to struggle just to survive.” The hard freeze almost halted biological activity, but when the ice retreated, life rebounded in surprising ways.

Later, for the lush Mesozoic Era, Poppick walks the Morrison Formation in the American West, showing how warm, wet climates and expansive floodplains allowed dinosaurs to thrive. She explains that the appearance of muddy floodplains “provided the ideal environment for late-stage terrestrial ecosystems to flourish,” connecting sedimentary change directly to the evolution of life. The greenhouse conditions of the Late Jurassic period didn’t just shape the land—they set the stage for a thriving of giants, painting a picture of Earth as a dynamic, living system.

Poppick’s emphasis on fieldwork—the embodied, place-based practice of geology—is one of the book’s most compelling features. She grounds each narrative in real sites, from mine shafts to desert outcrops, guided by practicing geoscientists whose observations she weaves seamlessly into the story. As she writes of a journey through Wyoming alongside paleontologists:

The three of us piled into the black F150 and began making our way down a patchwork of ranch roads that would bring us to the Jurassic Mile. The faded greens of prickly pear cactus, juniper, and sagebrush covered the red hills in the distance, where scorpions and rattlesnakes scuttled in dusty shadows. These venomous creatures, I was warned, would pose the most immediate threat to us at the dig. But during the time when the strata in those hills were first accumulating, the most immediate threats would have been far more conspicuous and would have sent everything else creeping into the shadows. While the herbivorous sauropods we would be digging up would not have been particularly menacing, they would have coexisted alongside more blood-thirsty carnivores.

Moments like this make the rock record tangible, showing readers how geologists read Earth’s history directly from the land itself.

Though the book focuses on events far removed from human history, its relevance to the present is implicit throughout. Poppick does not directly dwell on anthropogenic climate change, but the parallels between past intervals of major climate change, including greenhouse gas–forced warming, and today’s rapidly warming world are clear. The reader is left to draw their own connections between deep-time perturbations and current trajectories.

In an era when Earth systems science is more urgent than ever, Strata offers a public-facing model of geologic thinking. Poppick not only recounts the past, but she also demonstrates how we come to know it, through rock, time, and patient inquiry. In doing so, the book becomes an argument for why geology matters.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.