Growing the Great Green Wall

By Maxim Samson

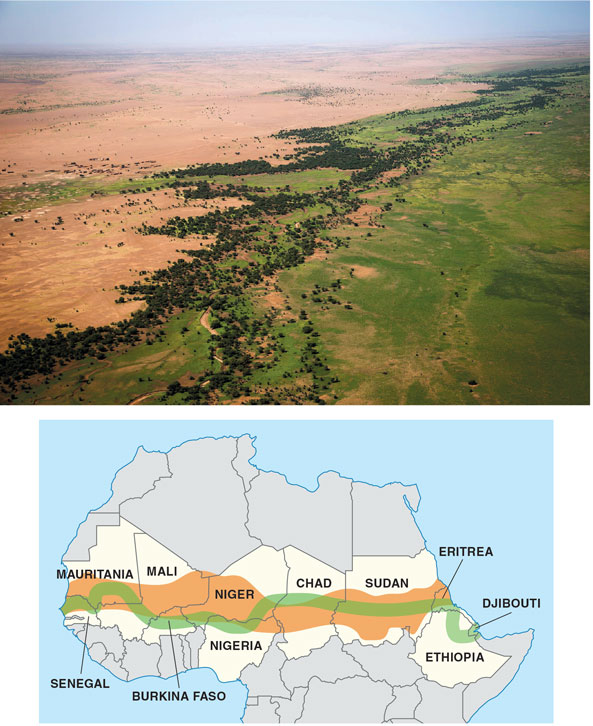

A collaborative effort spanning the width of Africa is planting a verdant barrier of trees and traditional agriculture to protect the Sahel from desertification.

A collaborative effort spanning the width of Africa is planting a verdant barrier of trees and traditional agriculture to protect the Sahel from desertification.

The heat is oppressive. Weary birds drift across the sky, yearning to escape the blistering Sun. Below, the soil is being baked to diamond hardness, its value diminishing with every moment. Grasses dry to matchsticks; skinny goats teeter and swoon. Hunger and despair are etched on the haggard faces of people who, with the shifting sands of time, reap little more than an early glimpse into an apocalyptic future, as a rapidly changing climate drives new population movements, new pressures, and new conflicts.

Stretching for approximately 6,000 kilometers from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, the Sahel is a continuous belt of semiarid land between the dry Sahara to the north and the wetter savannas to the south. Depending on one’s definition, the Sahel intersects at least nine countries—Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, and Eritrea—and arguably the Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Cameroon, Ethiopia, and Djibouti as well.

Evidence of an extraordinary past remains in the architecture of various medieval cities along the region’s main trans-Saharan trading routes. For the majority of the Sahel’s inhabitants today, however, the fabled histories of Chinguetti in Mauritania (a popular gathering place for Muslim pilgrims heading to Mecca, and an important repository of Koranic texts) and Timbuktu in Mali (a flourishing and profoundly interconnected hub for scholars and traders that far outstrips its mythologized “far-off” reputation) are of little consequence. Marred by drought, poverty, disease, and bloodshed, this once-illustrious strip of land has metamorphosed into the world’s biggest crisis zone.

Thierry Berrod, Mona Lisa Production/Science Source

As much as the Sahel refers geographically to the various lands joined together at the desert’s edge, its contemporary connective relevance is far more fluid. The region ties together more than 100 million people who face challenges unimaginable almost anywhere else on the planet.

At the heart of the matter is desertification: The Sahara is now as much as 18 percent larger than it was a century ago. It is easy to blame this rapidly changing geography on climate change. Temperatures in the Sahel are rising 1.5 times faster than the global average and are projected to increase by another 3 to 5 degrees Celsius by 2050. Considering that in some places temperatures can already push 50 degrees, this region is quite literally feeling the heat more than anywhere else on Earth. Coupled with an abbreviated summer rainy season, especially in the west, and a winter dry season that is seeing increasingly intense winds from the Sahara bring thick clouds of dust, forests and fields are degenerating before people’s eyes.

However, climate change is not the only impetus behind the growing desert. Alongside the Sahel’s multi-decadal increase in temperature and decline in rainfall, human activities have left once-vegetated ground bare. Whether directly or not, an underlying cause is the Sahel’s rapid population growth, as dazzling as the Sun overhead. By virtue of a well-founded fear that many children won’t survive until adulthood, a widespread belief that more children means more chances of economic success, and religious and cultural expectations that champion large families over family planning, the Sahel is the most fertile region in the world—in terms of demographics. At a little less than seven children per woman, Niger’s fertility rate is three times above the global average and over 70 percent higher than the average of the world’s least developed countries. Add to that the fact that nearly two-thirds of people in the Sahel are under 25 years old, most of whom still have plenty of child-rearing years ahead of them, and it’s clear that the region faces near-irresolvable dilemmas, both demographic and environmental.

Continued population growth here is a given: According to current projections, the region could be home to 330 million people by 2050, and double that by 2100. The problem is that productive land isn’t expanding at the same rate. Worse, due to a combination of climate change and weak government regulations and oversight, it’s diminishing. And so, with increasing pressure placed on fewer and fewer shreds of viable terrain to feed more and more people, deforestation, over-cultivation, and overgrazing now run rampant, driving the region’s natural resources to a breaking point. When the rain finally falls—which it tends to do as torrential downpours—it can prove less a comfort than a curse, washing away the nutrient-rich topsoil, engulfing exhausted communities in floodwater, and attracting biblical swarms of desert locusts so dense they are capable of forcing passenger planes to divert.

Confronted with these taxing conditions, many Sahelians have opted to migrate to the few relatively arable provinces in the region, or to urban or coastal areas beyond. However, most of these migrants continue to face a series of modern plagues. Whereas for centuries herders tended to be welcomed by southern farmers because their animals would fertilize their fields, today violent clashes over increasingly scarce resources have become all too frequent, particularly where legal rights to land are inconsistent or unclear. Catalyzed by the rise of ethnically based militias, Islamist groups including Boko Haram and Islamic State have expanded across the Sahel, seeking to exploit these fragile states’ general lack of political stability.

Each “brick” of the Great Green Wall has its own idiosyncrasies appropriate to local conditions and knowledge.

This medley of desertification, destruction, and disorder has undermined the prospect of meaningful gains being made in other key areas of society—the sort of advances that would help alleviate some of the problems at the region’s root. Unrelenting violence has both exacerbated and been fueled by local communities’ difficulties in accessing essential resources around the redundantly named Lake Chad (Chad literally translates as lake), a water body that shrank by more than 90 percent between the 1960s and 1990s, primarily due to climate change. In Burkina Faso, water and health care services have become entangled in combatants’ military strategy: Each assault ensures that these necessities remain outside the reach of a growing number of people.

Yet beyond the region’s trifecta of interconnected challenges—climate change, overpopulation, and conflict—a less widely recognized factor shapes and unites the Sahel. For centuries, nomadic and seminomadic groups have journeyed vast distances across the Sahel and Sahara, seeking to maximize the seasonal pastures in different regions without overexploiting them. Merchants and their camel caravans have traditionally relied on Indigenous groups’ familiarity with the desert, following meticulously defined itineraries between oases to traverse some of the planet’s most arid natural landscapes.

Although these relatively small numbers of periodic travelers have historically connected the Sahel in a somewhat tenuous way, today an ambitious initiative seeks to materialize the region’s long-standing ties and bring overdue advantages to millions. In contrast to the many walls intended to divide and exclude, the Great Green Wall initiative—which was founded in 2007—shows that walls can have a productive, future-facing function. Both a barrier against desertification and a unifier of ruptured societies, the enterprise encapsulates the latent potential of geographical connection in restoring and reviving our world. The Great Green Wall demonstrates that, through mindful action, commitment, and collaboration, we can transform our broken surroundings.

Meandering from west to east across sub-Saharan Africa, the Great Green Wall is an ongoing project to create the world’s largest living structure, over three times longer than the world’s current record holder, the Great Barrier Reef. At this endeavor’s core is the earnest aim of restoring 100 million hectares of the planet’s most degraded terrain by 2030, along an uninterrupted 8,000-kilometer course from Senegal to Djibouti.

Although the original plan was to connect Africa’s west and east coasts with a continuous 15-kilometer-wide wall of drought-tolerant trees, the Great Green Wall has since evolved into a linear mosaic of productive landscapes, including forests as well as grasslands, savannas, farms, and community gardens. Even though the new vision may sound less grandiose, its construction is far more realistic. Practicalities are paramount: A wall broken up by long treeless gaps isn’t really a wall.

MINUSMA/Marco Dormino/Flickr/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; Sevgart/Wikimedia/CC BY SA 4.0

In order for this project to succeed, each and every section needs to be intact. The Sahel, after all, is a necessarily interconnected region, where land degradation locally can quickly set in motion a domino effect of migration, resource pressure, violence, and extremism across a much wider area.

By contrast, regeneration promises to spark further benefits. The cultivation of food should act as a safeguard against malnutrition, still a life-threatening issue for millions of people in the Sahel. With enhanced food security, as well as the intended creation of 10 million green jobs in some of the world’s most destitute rural areas, regional security will hopefully follow: Improved living conditions will provide less sustenance for the growth and spread of extremist groups, whose recruitment largely depends on exploiting citizens’ vulnerability. And as if these remarkable advantages weren’t enough on their own, the Great Green Wall’s relevance stretches far beyond the Sahel. Through targeting the capture and storage of 250 million tons of carbon, the region—which contributes the least to global carbon emissions relative to its population size, yet is one of the most sensitive to climate change’s impacts—would mitigate the planet’s greatest existential threat. Given these varied and intrinsically international benefits, it is unsurprising that the Great Green Wall has captured the interest of a wide range of partners in the Sahel and beyond, including the United Nations, the World Bank, the African Development Bank, the European Union, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, foreign governments, nonprofits, and private actors.

With all eyes suddenly on the Sahel, the question then becomes: Who leads this revolutionary initiative? The answer, so obvious on the surface and yet sadly so radical in modern history, is Africans. For decades, sub-Saharan landscapes tended to be managed according to the priorities and assumptions of powerful people in distant places, uprooting Sahelian communities’ distinctive management of familiar lands in the process. The Great Green Wall can be regarded as the culmination of this shift in emphasis, from the foisting of land-use practices to serve the needs of others, to timely interventions nevertheless conceived according to an outsider’s assumption of Sahelian needs, to, finally, a project designed for Africans by Africans.

That said, as challenging as it is to transform lands, it can be just as difficult to change mindsets. The Great Green Wall epitomizes this unfortunate reality, because in its original, tangibly connective form, the project better resembled a distinctly foreign and flawed approach to restoring arid landscapes: mass tree planting.

What many rural Sahelian communities already knew, but the Great Green Wall’s policymakers seemingly didn’t, is that land degradation at the desert’s edge is not owing to the desert itself; the Sahara only looks like it’s advancing. The truth is, trees are not well suited to being anti-desert barriers—not unless the soil and water supply are improved first, anyway. Unfortunately, the initiative was forced to learn this lesson the hard way: Northern Nigeria noticed that three-quarters of its 50 million new trees had died within just two months. The original vision of connecting the Sahel with trees needed some significant tweaking, and quickly.

G Gray Tappan/USGS

To succeed, local knowledge and expertise—which were largely overlooked in the first few years of the initiative—would have to constitute key building blocks. On top of the ecological challenges of growing trees on parched lands, it was implausible to expect time-poor communities to travel long distances to the remotest areas of the Sahel to tend to saplings, or to refrain from clearing trees whenever they needed fuel. Cognizant of these issues, in place of a one-size-fits-all strategy of creating a coast-to-coast line of trees, the Great Green Wall has come to represent a varied patchwork of sustainable land and water management practices, in which communities restore their lands in ways that best retain and respect their uniqueness, while serving their own fundamental needs. It may be less obviously connective than its foreign-inspired roots, but in both its heterogeneity and its groundedness, the new Great Green Wall is genuinely African.

Is it still a wall, though? Reflecting the symbolic power of lengthy, connective landmarks, the concept of a green wall is so irresistible that the name has remained in place even as the program has evolved from a straightforward tree barrier into a far more comprehensive rural development initiative. In emphasizing a collaborative approach to creating lush, productive landscapes that are distinct from one another and yet interconnected, this strategy represents a reworking rather than a renunciation of the initial vision. It doesn’t matter that it won’t look like a wall per se. As long as it is able to achieve the objectives of the original vision, devoid of holes where land practices continue to exacerbate desertification, it will serve as a wall-in-kind. Ultimately, the benefits are all that really matter; the rest is just semantics.

Each “brick” of the wall has its own idiosyncrasies appropriate to local conditions and knowledge. In northern Burkina Faso and neighboring areas, for example, a traditional agricultural technique for increasing soil fertility called zaï (elsewhere known as tassa or towalen) has been revived, enhanced, and rolled out ever more widely since the early 1980s, thanks in no small part to the vision and energy of the late Burkinabé agronomist Yacouba Sawadogo. This method, which involves digging a grid of small pits into degraded soil and placing a couple of handfuls of organic matter at the bottom to attract termites, offers important advantages in regions where the soil is infertile, rainfall is sporadic, and resources are scarce. The termites dig tunnels in the ground, allowing more rainwater to infiltrate into the soil, and process the organic matter so that nutrients in the soil become more readily available to any seeds carried into these moist pockets by wind, rain, or hand. With the endorsement of farmers cultivating significant yields of millet and sorghum, zaï has become an increasingly common feature of long stretches of the Great Green Wall’s western segments, bringing new, verdant life to landscapes that only recently seemed beyond repair.

Michael Dwyer/Alamy Images

Other agricultural practices similarly manifest a frugal use of local materials, and despite their varied appearance, they share the objective of capturing as much of nature’s essential resources as possible. Often conjointly with zaï, and particularly where there is a slight gradient, many western Sahelian farmers choose to place rocks along natural contours to create long stony bunds or lines. When the rain falls, these unbroken barriers slow surface runoff so that more water soaks into—rather than rushing away from—farmers’ fields, while trapping valuable sediments and organic matter.

In Niger, another popular method on gentle slopes is to construct crescent-shaped bunds called demi-lunes (half-moons) capable of trapping surface runoff and organic matter immediately following rainfall. In the clay plains of eastern Sudan, series of interconnected U-shaped earthen bunds, called teras, are traditionally used to prepare the soil for the cultivation of Indigenous cereals such as sorghum (which can tolerate both drought and temporary waterlogging), while in Eritrea and Ethiopia terrace farming is being expanded along the slopes.

In Chad, the prehistoric practice of forest gardening has been modernized as a regenerative agroforestry technique, whereby carefully selected trees are intentionally integrated with fruit and vegetable crops to create a biodiverse and self-perpetuating ecosystem. With the significant support of the U.S. nonprofit organization Trees for the Future, this strategy is, in effect, creating a green wall both edible and defensive, providing local communities with food and medicine, and protecting crops from wind and water erosion.

Most eye-catching of all are Senegal’s tolou keur, community gardens comprising a series of concentric circles. The outer halo of these gardens is made up of drought-resistant trees such as baobab and mahogany, which protect the smaller rings of food-producing and medicinal species within. Conceived by the Senegalese agricultural engineer Aly Ndiaye as a necessary response to declining imports, among other disruptions, during the COVID-19 pandemic, tolou keur are now regarded by local communities as essential laboratories for further experimentation as well as resource provision. Along with curving permeable rock dams, round bouli ponds, strip-like rainwater trenches, V- and diamond-shaped micro-catchments, webs of live fences and field hedges, and parallel plowed troughs, these human interventions are helping to shape distinctly geometric landscapes across the Sahel.

Reuters/Zohra Bensemra

Thanks to the opportunities provided by the initiative for knowledge sharing across vast distances, various modern methods, including some conceived by people foreign to the Sahel, are also now being implemented throughout the region. Perhaps none is more noteworthy than farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR), which, having been successfully pioneered by the Australian agronomist, missionary, and “forest maker” Tony Rinaudo in Niger in the early 1980s, is today being replicated across swathes of the western Sahel. FMNR’s rather inelegant name conceals its conceptual simplicity. Effectively, it requires farmers to take a relatively hands-off approach to their fields, intentionally not planting any trees and instead systematically pruning and nurturing those species that sprout spontaneously from the soil. FMNR thus offers an ideal balance between the human and natural worlds, neither allowing the land to go fully wild, nor clearing or farming it to excess, all while enabling farmers to benefit from trees’ ability to protect their crops from wind and windblown sand and to supply fodder for their livestock.

What this assortment of strategies brings to light is a growing appreciation that cutting-edge, high-tech, but generally inflexible solutions requiring expensive maintenance are not the Sahel’s reality. Simple, low-cost improvements on locally familiar practices tend to be far more appropriate to the region’s resource-scarce environment, with the very best options being those capable of addressing multiple needs simultaneously. Just as climate change, desertification, and biodiversity loss operate as a vicious cycle trimming residents’ incomes, land rehabilitation can increase groundwater recharge and also support the development of farms and vegetable gardens capable of feeding stomachs and wallets.

If its reported statistics are to be believed, so far nowhere has been more adroit at rehabilitating its lands than Ethiopia. At the beginning of the 20th century, forests covered 40 percent of Ethiopia (and 90 percent of its highlands), but rampant deforestation, especially in the first half of the country’s communist Derg dictatorship in the mid-1970s and early 1980s, left only 4 percent of its lands forested by the turn of the millennium. However, Ethiopia also has a long tradition of seeking symbiosis between the human, natural, and spiritual worlds, represented best by its tens of thousands of church forests. Miniature Gardens of Eden, these ring-shaped woodlands, some of which are now safeguarded by stone walls, continue to be preserved as extensions of the sacred sites they surround, and in return offer congregants space for contemplation and protection from wind and heat.

The Great Green Wall’s significance is not merely environmental: It also represents a mutual, physical intermediary between people whose historic affiliations have been largely erased from the map.

Ethiopia’s church forests can appear like extraordinary remnants of a lush past, and yet the country’s viridescent history may not be as lost as it once seemed. Aided, no doubt, by the country’s recent issuance of landholding certificates to more than 360,000 households, public buy-in regarding its ongoing Green Legacy initiative is quite astonishing. By 2020, Ethiopia claimed to have restored 12 million hectares of degraded land (mostly outside the official Great Green Wall intervention zone), representing over two-thirds of the initiative’s total to date, and putting the country 80 percent of the way toward its own 2030 target. Reflecting its inhabitants’ deep-rooted reverence for trees, Ethiopia subsequently reported the planting of 25 billion seedlings between 2019 and 2022, and is currently striving to emulate this achievement by 2026. Most remarkably of all, on July 17, 2023, millions of Ethiopians from all walks of life collaborated to plant more than 500 million trees, beating the country’s previous record of 350 million, set four years earlier. Even though it’s possible that the Ethiopian government has been a little cavalier with its data, any achievements even remotely close to these figures deserve to be congratulated rather than scorned.

Another major success story is a nation at the opposite end of the Great Green Wall, Senegal, where the planting of 12 million native trees in less than a decade seeks to protect crops from fierce gusts and citizens from economic insecurity. Within its rejuvenated tree belt, perhaps no species better encapsulates this country’s shrewdness than a thorny tree whose scientific name, Senegalia senegal, affirms its indigeneity and hence its natural survival advantages there. This acacia also provides huge economic value: Its gum arabic is used as an emulsifier in soft drinks and confectionery, as a base material in incense, as a thickener in shoe polish, and as a binder for watercolor paints. The species is therefore almost as immune to deforestation as it is to drought.

Having long been dismissed as the world’s most hopeless region, the Sahel is emerging like a phoenix, resurrected from disaster through the foresight, know-how, and verve of African people. The Great Green Wall in its modern iteration epitomizes a growing recognition internationally that Sahelian people can take charge of their own affairs. The region’s farmers are increasingly lauded for sharing their innovative cultivation methods with their counterparts throughout the region. In so doing, they are, in effect, transcending the borders created by colonial powers in the past. In this sense, the Great Green Wall’s significance is not merely environmental: It also represents a mutual, physical intermediary between people whose historic affiliations have been largely erased from the map. With a clear and shared vision for the region’s future now in place, certain stretches of the Sahel are gradually being transformed into flourishing emerald landscapes, with a view to one day becoming interlocking stakes of this expanding palisade.

Few initiatives can claim to be as inspirational as the Great Green Wall in attempting to unify broad and diverse societies with a shared, pressing purpose. In the region most severely affected by land degradation and desertification, where the soil is thin and rain is unreliable, here is a project whose mission is to grow not just plants, but also the fertile ground on which they rely. In countries where extreme poverty is a fact of life for millions, the Great Green Wall is an opportunity to create new economic opportunities, harnessing nature’s resilience to glean value from its most essential resources. Long marked by desperation and division, the Sahel may seem an unlikely place to find connection. But should the Great Green Wall mature and ripen as a fully integrated architecture of green and productive landscapes, as the uninterrupted green river from ocean to sea depicted on the initiative’s official emblem, it will be living proof that humanity can work together to change itself and its environments for the better. More than just a symbol of African ingenuity, with the potential to alter how the continent is perceived internationally, and more than just a show of political will at the global scale, the Great Green Wall will be a proclamation to the rest of the world that the future never need be inevitable. If the world’s most disadvantaged region can overcome its greatest threats, then surely anywhere can.

As testament to its international relevance, the Great Green Wall makes important contributions to a staggering 15 of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for a better world by 2030 and all three of the conventions (on climate change, biological diversity, and desertification) created by the renowned 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. It also supports the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and SDG 15’s shared objective of achieving land degradation neutrality by 2030. It also acts as a flagship for the present UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and complements the African Forest Landscape Restoration initiative’s pledge to the Bonn Challenge, which seeks to restore 350 million hectares of degraded and deforested land by 2030.

Already, the project has served as a green light for other endeavors whose mission is to advantage people and places with the biggest need. Impressed by the progress being made in parts of the Sahel, and conscious of the failures of its past decision to plant Aleppo pines (which demand lots of water, are susceptible to disease, and have limited use for local communities) as the basis of its own green barrier, Algeria has opted to relaunch its afforestation project with far greater species diversity than before. At the other end of the continent, plans to create a southern Great Green Wall are quickly taking shape, again with an emphasis on uncovering, rejuvenating, and sharing Indigenous farming techniques suited to drylands, including the Kalahari and Namib deserts and South Africa’s Karoo.

Si Yuan/Xinhua/Alamy Live News

When it comes to restoring degraded lands, collaboration among stakeholders, countries, and projects is essential: One must not lose sight of the fact that improvements to water, soil, and vegetation are mutually reinforcing, and act as the key to solving a broad range of economic, social, and political issues. Accordingly, a multitude of initiatives in the Sahel have been directly harmonized with the Great Green Wall, from renewable energy to food security, and from climate resilience to species conservation.

For instance, the African Development Bank’s ambition to create the world’s largest solar zone in the Sahel, capable of supplying clean, renewable energy to a quarter of a billion people across the 11 original Great Green Wall countries by 2030, is explicitly tied to the initiative. For one thing, by drastically reducing energy poverty throughout the Sahel, this Desert to Power Initiative ought to dissuade residents from cutting down the trees grown throughout the region for fuel. For another, through introducing solar-powered drip-irrigation systems, which enable farmers to grow more crops with less water and energy, the project aims to increase agricultural productivity and food security—both key elements of the Great Green Wall’s mission as well—while deterring people from practicing less sustainable methods that threaten the wall’s integrity.

Rather than being simply a barricade against the desert, the Great Green Wall has also become a bridge, bringing together various people and places in the intricate and knotty fight against land degradation, ecosystem damage, climate change, and extreme poverty and hunger. Backed by phenomenal political will on an international scale, the initiative’s consequentiality—real and symbolic, local and global—is hard to overstate.

As a rare but necessary example of the contemporary Sahelian nations working together, the Great Green Wall uses the power of connection to mitigate and reverse this vast belt’s most formidable perils. The problem is that the same qualities that provide cause for hope and which might hold the endeavor (and, by extension, the region) together also risk tearing it apart. The initiative, in short, is characterized by paradoxes that threaten its eventual realization.

First is the fundamental but thorny matter of whether the Great Green Wall is a top-down initiative overseen by a central body (in line with the original tree-barrier vision), or a genuinely bottom-up enterprise led by different local communities (as implied by the new concept). In reality, the project now resembles something of a mishmash, being nominally coordinated by the Pan-African Agency of the Great Green Wall (PAAGGW), a Mauritanian-based regional authority that finds itself regularly bypassed by funders keen to control how their contributions are spent. PAAGGW and the African Union have struggled to determine how much money is available, who is funding what, and whether the finances represent loans, grants, or otherwise, the conditions for which vary greatly.

To complicate matters further, the Sahelian countries are often hesitant to accept loans, particularly for environmental projects, fearing that they will only compound their ceaseless and traumatic debt crises. Together with a relative lack of independent research tracking how much funding each country has mobilized and the progress it has made toward its targets (how many planted trees have actually survived, for instance), the question of who does or should lead the initiative risks frustrating its future.

An associated paradox pertains to donors. Although the initiative is directly relevant to a wide range of environmental and development objectives, due to its sheer scale and scope—not to mention a paucity of centralized information about specific Great Green Wall programs—prospective donors often struggle to determine where and how they should help. And even though the Great Green Wall’s emphasis on community participation ought to encourage local populations to contribute, because it comprises numerous smaller projects necessarily distinctive to local contexts, there is a real risk that many will be treated as discrete silos or will remain out of the limelight necessary for attracting wider investment.

So far, Ethiopia and Nigeria have been among the most proactive partner countries in obtaining funds and implementing new projects, but owing to the considerable strain applied by their rapidly growing populations across significant portions of territory, they are also under the most pressure to continue attracting financial support, certainly compared with far smaller nations such as Djibouti. Size commands the attention of funders, but it demands that they spend more as well.

A further challenge with managing such a colossal project simultaneously from the grassroots and from above is ensuring close alignment between parties. Despite the theoretical flexibility of the Great Green Wall as an umbrella initiative, national land-use laws, particularly with regard to tree felling, still tend to demand burdensome and slow bureaucratic procedures, which can sap enthusiasm for the initiative.

In much of the western Sahel, the mixed legacy of customary law and colonialism means that agricultural and pastoral lands continue to be owned by the state. Additionally, rural residents can find it far harder to obtain legal title to lands their families have managed for generations than do foreign investors and loggers, whose interests tend to be narrower and whose actions are more likely to be exploitative. As a consequence, many communities are understandably reluctant to engage in sustainable practices such as FMNR or even to grow trees in the first place: Not only do they see little incentive to manage trees, but doing so also risks punishment from powerful figures already liable to treat them with suspicion.

As long as the wall has cracks, it is effectively just a loosely affiliated collection of gardens, beneficial to local residents in select areas but unlikely to bring lasting peace further afield.

It doesn’t matter that Indigenous peoples globally are incomparable stewards of the environment, protecting as much as 85 percent of the planet’s biodiversity despite representing less than 5 percent of its population. In the Sahel, the established logic is that the authorities know best. Yet without local knowledge, engagement, and collaboration from West to East Africa, there will never be a Great Green Wall.

The question of whether the Great Green Wall is a truly unified initiative or a miscellany of small-scale schemes looms large again: Oversight from above is crucial to integrating diverse projects into a continuous strip of regreened land, but if local residents are unable to take ownership of their own needs and undertake practices that make sense to them, there will be little to connect.

As long as the wall has cracks, it’s effectively just a loosely affiliated collection of scattered gardens, beneficial to local residents in select areas but unlikely to bring lasting peace further afield. And at the time of writing, the existence of mere cracks would be regarded as a triumph. Africa as a whole saw a far larger net loss of forest area than any other part of the world between 2010 and 2020; and as of 2023, the Great Green Wall remained just one-fifth of the way toward its land restoration target.

Recognizing these obstacles is not to understate the Great Green Wall’s laudable achievements. Over time, the landscape of much of the Sahel is becoming increasingly heterogeneous and complex, its fields boasting a growing diversity of flora while its pastures accommodate larger herds of cattle, goats, and sheep. Even though plenty of young adults still believe, not without valid reason, that their job prospects are superior in sub-Saharan Africa’s swelling cities, a good many others are increasingly willing to stay and work together to bring life to injured plots. A new “ecopreneur” class has emerged among women, who, instead of spending significant portions of the day collecting wood for fuel, can tend to community gardens and manage shops. More and more children enjoy diverse, nutritious diets, setting them up for success at school. These accomplishments all provide real hope that the world’s most disadvantaged region is sprouting a better future for its inhabitants. The challenge is to close the wall’s many remaining gaps.

Walls are often viewed as forbidding entities conveying separation and hostility. The Great Green Wall has no such patina. It proves that walls don’t need to need to isolate deprecated communities. Instead, they can provide insulation against real issues, both human-made and natural, which in one way or another affect us all (and for which, through our consumption habits and energy use, we are in turn at least partly responsible). If completed as planned, the Great Green Wall will, in essence, be both a symbol of hope as well as a vehicle of peace and prosperity, protective and productive all at once.

Reprinted with permission from Earth Shapers: How We Mapped and Mastered the World, from the Panama Canal to the Baltic Way by Maxim Samson, published by the University of Chicago Press. First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Profile Books Ltd. © 2025 by Maxim Samson. Website

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.