This Article From Issue

November-December 2025

Volume 113, Number 6

Page 376

EARTHLY MATERIALS: Journeys Through Our Bodies’ Emissions, Excretions, and Disintegrations. Cutter Wood. 384 pp. Mariner Books, 2025. $29.95.

As soon as I read the title of this book, Earthly Materials: Journeys Through Our Bodies’ Emissions, Excretions, and Disintegrations, I knew I had to review it. For most people, those words—“emissions,” “excretions,” and “disintegrations”—are humiliations of the body that, with any luck, are never discussed with anyone else—ever. Yet here they are, fully exposed.

Author Cutter Wood is not a scientist. He’s not a physician, duty bound to sometimes ask about these bodily products. He’s a guy with an MFA and an interest in these gross bodily outputs—mucus, stool, blood, breath, and flatus. Simply based on that, I was ready to follow him deep into the nooks and crannies of our various corporeal factories and their emanations.

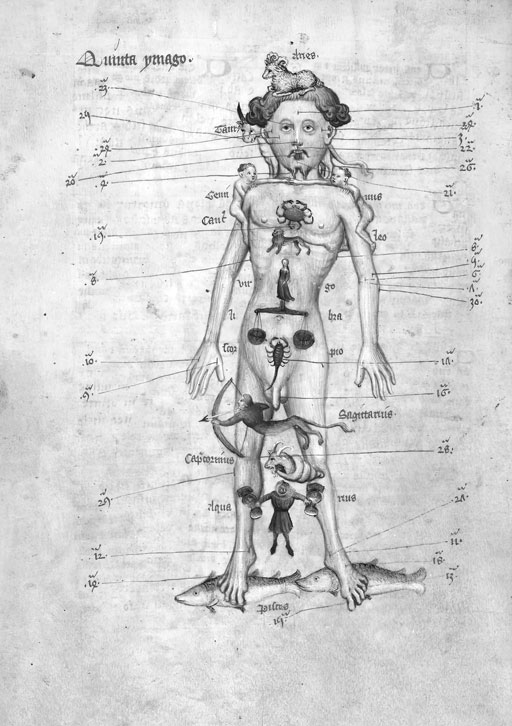

Medieval bloodletting diagram, Liber Cosmographiae, John De Foxton, 1408

And Wood is ready to go there, right from the start. The book opens with a fart joke. Sure, it’s found stamped in cuneiform from an anonymous Sumerian some two thousand years before the birth of Jesus, but it’s still a fart joke. Wood goes on to show how our effluvia shaped our culture, our architecture, and our societies. That contrast characterizes much of this delightful and weird book. Beneath each chapter heading, Cutter includes a pithy quotation from a thinker drawn from history, ranging from the 4th century theologian Augustine of Hippo to the contemporary poet Claudia Rankine. Such dignity is balanced by a list of the other words the specific substance goes by, ranging from delicate euphemism to the shouted expletives of the joyful eight-year-old discovering the thrilling grossness of the body. For instance, the chapter on vomit starts with a line from the Bible then drops down to the schoolyard, as shown below:

As a dog returns to his vomit, so a fool returns to his folly. Proverbs 26:11

Terms

n. barf, puke, throw-up, spit-up, mess, chunks, lunch, cookies

v. barf, yarf, spew, spit up, burp up (mostly in infants) . . . chunder, yak, ralph, regurg, blow chunks, boot, bow down before the porcelain goddess, drive the porcelain bus, Technicolor yawn, bushusuru (Japanese, translating literally as “do a Bush” after former president George H. W. Bush inadvertently vomited on then-prime minister Kiichi Miyazawa) . . .

Images depicting some aspect of the specific excretion come next, ranging in tone from an elegant photograph of a crystallized tear to a 19th-century drawing by the Japanese artist He-Gassen, of what is described as a “fart battle.”

After each chapter’s introductory definitions and images, Wood provides a soupçon of science, which the author calls a “biological prologue.” He then takes the reader through history, culture, philosophy, and personal anecdotes to focus on one aspect of each emission. For example, readers learn about a lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that studies mucus, go deep into Reddit to assess sentiments about masturbation, and read about a business in Florida run by a suburban mom who is now serving time for trafficking in stolen baby formula.

Chapters are named after bodily fluids and most chapters are structured around two or three anecdotes linked to that substance. “Blood” opens with a story about a friend who discovers that she has BII (blood–injection–injury phobia), which triggers a significant physical response that results in fainting, while walking past a local church holding a blood drive. After Wood explains that even saying the word “blood” can be extremely triggering in some people with BII phobia, he provides a historical review of its etymology before taking a deep dive into the big business of blood that is not often seen by those who are donating said product. As he lies on a stretcher donating a pint of his own, the author muses about the motivation leading him and the dozen other co-contributors to give away their literal lifeblood.

Our largesse with our blood, Wood notes, is often triggered by tragedy. It can therefore be a little demoralizing to find out what then happens to the blood so freely given away: It’s sold. It’s a product that goes to pharmaceutical companies, academic research centers, and of course, hospitals. He writes,

And suddenly what you gave away for free ends up costing that kid with cancer a few thousand dollars . . . and the miraculous red stuff you thought was a big altruistic middle finger in capitalism’s face turns out to have been just another commodity on another market in a world where everything gets bought and sold eventually.

Wood’s storytelling style and approach to his material vary. In one chapter, he delves deep into a subreddit dedicated to the topic of not masturbating. In another, he dips in and out of his own boyhood traditions surrounding flatulence, and hides historic digressions within a series of David Foster Wallace–length footnotes. Combined with the author’s casual (and sometimes gleefully gross) tone, the book can feel more like a series of blog posts than a collection of formal essays.

Wood also has an unfortunate love of lists and a grad-school-nerd glee in references that (at least for me) necessitated frequent Google searches that interrupt some of these otherwise entertaining pieces. But I forgave him when I found that the best place to read these brief treatises was in the bathroom, where I would have taken my phone anyway. Given the experience of reading the news these days, leafing through Earthly Materials is a much better way to spend these few moments of privacy.

The book ends with a summation of the earthly matters each of us leaves behind. It’s a humbling inventory:

14,000 liters of feces

33,000 liters of urine

6,000 liters of tears

2 to 3 liters of menstrual blood

100,000 liters of mucus

2 million feet of hair

Then, at the end of life, there is the body itself, with all its proteins and fats and bones. But what we really leave behind that lasts, concludes Wood, are words. And if you are a certain kind of person, you will perhaps collect those words in a book—an object that, with luck, will live on. Fingers crossed, Cutter Wood.

With every topic, and with every emission that Wood takes on, he reminds us that “there’s more to discover, as every child recognizes when they put their finger up their nose. It’s all a matter of how far you’re willing to go.” And on these matters, Wood is willing to go all the way.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.