This Article From Issue

March-April 2010

Volume 98, Number 2

Page 162

DOI: 10.1511/2010.83.162

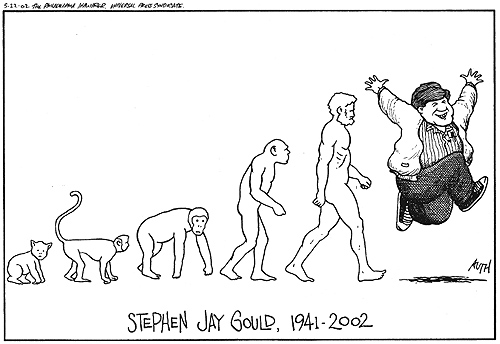

STEPHEN JAY GOULD: Reflections on His View of Life. Warren D. Allmon, Patricia H. Kelley and Robert M. Ross, editors. xiv + 400 pp. Oxford University Press, 2009. $34.95.

Stephen Jay Gould was an immensely charismatic, insightful and influential, but ultimately ambiguous, figure in American academic life. To Americans outside the life sciences proper, he was evolutionary biology. His wonderful essay collections articulated a vision of that discipline—its history, its importance and also its limits. One of the traits that made Gould so appealing to many in the humanities and social sciences is that he claimed neither too much nor too little for his discipline. In his books, evolutionary biology speaks to great issues concerning the universe and our place in it, but not so loudly as to drown out other voices. He had none of the apparently imperialist ambitions of that talented and equally passionate spokesman of biology Edward O. Wilson. It is no coincidence that the humanist intelligentsia have given a much friendlier reception to Gould than to Wilson. Gould’s work is appealing to philosophers like me because it trades in big, but difficult and theoretically contested, ideas: the role of accident and the contingency of history; the relation between large-scale pattern and local process in the history of life; the role of social forces in the life of science.

Within the life sciences, Gould is regarded with more ambivalence. He gets credit (with others) for having made paleobiology again central to evolutionary biology. He did so by challenging theorists with patterns in the historical record that were at first appearance puzzling; if received views of evolutionary mechanism were correct, Gould argued, those patterns should not be there. The first and most famous such challenge grew from his work with Niles Eldredge on punctuated equilibrium, but there were more to come.

Despite this important legacy, Gould’s own place in the history of evolutionary biology is not secure. In late 2009, I attended an important celebration of Darwin’s legacy at the University of Chicago, in which participants reviewed the current state of evolutionary biology and anticipated its future. Gould and his agenda were almost invisible. No doubt this was in part an accident of the choice of speakers. But it is in part a consequence of Gould’s ambivalence regarding, or perhaps even hostility toward, core growth points in biology: cladistics, population genetics, ecology.

Gould was an early force in one of the major recent developments in biology: the growth of evolutionary developmental biology, and the idea that the variation on which selection works is channeled by deeply conserved and widely shared developmental mechanisms. Gould’s first book, Ontogeny and Phylogeny (1977), was about the antecedents of this movement, and in his essays and monographs he regularly returned to this developing set of ideas. He did so to articulate his vision of natural selection as an important but constrained force in evolution. But in the past 20 years, evolutionary biology has been transformed in other ways too. Perhaps the most important is that cladistics—systematic, methodologically self-conscious, formally sophisticated phylogenetic inference—has become the dominant method of classification. This phylogenetic inference engine has made it possible to identify trees of life with much greater reliability and to test adaptationist hypotheses and their rivals far more rigorously. Even though Gould had been early to see the problems of impressionistic adaptationist theorizing, his own work responded very little to these changes in evolutionary biology.

Likewise, Gould showed very little interest in the evolving state of population genetics; his last book, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, barely mentions it (W. D. Hamilton, for example, is not even in the index). This is surprising, because one recent development in population genetics had been the growth of multilevel models of selection. In The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, Gould does nod to these models, but he does little to connect them to his own ideas on hierarchical models of selection, which get very little formal development of any kind, let alone the kind of development that would connect them to the extending mainstream of evolutionary theory. Finally, Gould showed extraordinarily little interest in ecology and the processes that link population-level events to patterns in the history of life.

In short, although Gould was clearly an immensely fertile thinker whose ideas were deeply informed both by contemporary paleobiology and by the history of biology, in other respects his work is only partially connected to the mainstream of developing evolutionary thought. There is, therefore, room for a work that explores and reflects on the explicit connections that Gould made between his own ideas and the rest of his discipline, and that makes some implicit connections more explicit. Stephen Jay Gould: Reflections on His View of Life, edited by Warren D. Allmon, Patricia H. Kelley and Robert M. Ross, is an interesting collection of essays, but it does not quite do that, in part because it is an insider’s perspective and in part because some of the essays are of only local significance. For example, the chapters on Gould’s status as an educator, his role as an iconic left-liberal American intellectual, and his relations with those of his students who were religious will likely be of interest to no one outside the U.S. milieu and I would guess to very few people within it. The collection is not a Festschrift, but it does show an occasional tendency to decay in that direction.

One of the strongest chapters in the collection, to my mind, is “A Tree Grows in Queens: Stephen Jay Gould and Ecology,” by Allmon, Paul D. Morris and Linda C. Ivany. Allmon, Morris and Ivany try to explain the lack of an ecological footprint in Gould’s work. In their view, this is best explained by his skepticism about natural selection. It is true that the more strongly one believes that the tree of life is basically shaped by mass extinction (while thinking that the extinction in mass extinction does not depend on adaptation), the less important ecology is. The theory of punctuated equilibrium, too, plays down the importance of ecology through most of the life of a species. Although I am sure this must be part of the story, something is missing. Gould remained committed to the truth and importance of the punctuated equilibrium model of the life history of the typical species. He developed that model in partnership with Eldredge and (later) Elizabeth Vrba. But ecological disturbance remains central to Eldredge’s and Vrba’s conception of punctuated equilibrium and, more generally, to evolutionary change. Equilibrium is not forever. So for example, in contrast to Gould, Eldredge has written extensively on ecological organization and its relation to evolutionary hierarchy. Allmon, Morris and Ivany have put their finger on a crucial problem in interpreting Gould, but the problem remains unsolved.

Allmon is also the author of the fine chapter that opens the collection—“The Structure of Gould: Happenstance, Humanism, History, and the Unity of His View of Life.” Long and insightful, this essay is one of interpretation rather than assessment. It explores the relation between content and form in Gould’s work. The current norm of science is that research consists in the publication of peer-reviewed papers in specialist journals. As one nears retirement, it may be acceptable to switch to writing reflective what-does-it-all-mean review papers, and even a book or two: This is known as going through philosopause. Gould went through philosopause early, and Allmon attempts to explain why, connecting the form of Gould’s work as an essayist and book author with his humanism, his liberalism and his interest in exploring murky, large-scale questions. He broke with conventional norms of science writing not just because he wanted to reach more people, but because of what he wanted to say. The essay is interesting, but I think Allmon lets Gould off too lightly, especially in his discussion of the supposed early misreading of punctuated equilibrium. Gould’s early rhetoric on the revolutionary impact of that idea and his repeated flirtations with Richard Goldschmidt’s metaphors made it easy to read Gould as rejecting standard neo-Darwinian gradualism; at the time, I read him that way myself. And the discipline of peer review would certainly have improved The Structure of Evolutionary Theory.

Richard Bambach’s essay, “Diversity in the Fossil Record and Stephen Jay Gould’s Evolving View of the History of Life,” is also rewarding, although it is less ambitious than Allmon’s. Bambach offers a chronological overview of the most important feature of Gould’s purely scientific ideas: his emerging view of the basic patterns of life’s history. It is good to have this material assembled and presented so coherently. I would, however, have liked to see a rather franker assessment of these ideas. In Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (1989), Gould argues that if “the tape of life” were replayed from very slightly different initial conditions, the resulting tree of life would probably in no way resemble our actual biota. This was surely one of the most provocative of his ideas, and Simon Conway Morris replied at length in Life’s Solution, reaching utterly the opposite conclusion. At the end of the chapter, Bambach touches on this debate but says almost nothing to assess it.

In general, the other essays in this book have the same virtues as Bambach’s chapter. The editors, I suspect, think that Gould has been much misread and misunderstood, so most of the essays seek to state his views simply and without distracting polemic. As a result the collection is stronger on description than evaluation. I am not convinced that Gould has been so much misunderstood, and I would have preferred more assessment and less exposition. That said, I did enjoy reading the book.

Kim Sterelny divides his time between Victoria University of Wellington, where he holds a Personal Chair in Philosophy, and the Research School of Social Sciences at Australian National University in Canberra, where he is a professor of philosophy. He is the author of Thought in a Hostile World: The Evolution of Human Cognition (Blackwell, 2003), The Evolution of Agency and Other Essays (Cambridge University Press, 2001), Dawkins vs. Gould: The Survival of the Fittest (Totem Books, 2001) and The Representational Theory of Mind (Blackwell, 1991). He is also coauthor of several books, including What Is Biodiversity?, with James Maclaurin (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.