Magazine

September-October 2012

September-October 2012

Volume: 100 Number: 5

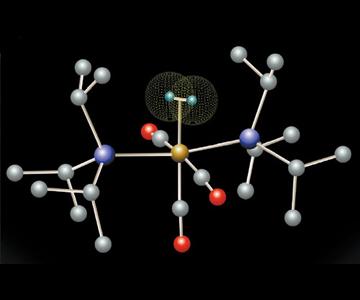

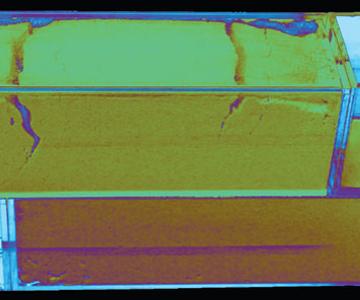

Transmission electron spectroscopy (TEM) images are taken by transmitting a beam of electrons through an ultra-thin sample. Interactions between the sample and the electrons, such as absorption or complex wave interference, create the contrast in the image. Electrons can provide much higher-resolution images than light, allowing atomic-level detail. On the cover, a grid used to support the thin samples is shown in red with its one-micrometer-diameter holes in blue, and a small flake of graphene is imaged in green. As Keith A. Jenkins explains in “Graphene in High-Frequency Electronics,” this single-atom-thick form of carbon has great potential for use in circuits, but scaling up the pieces to usable size has taken some work. Jenkins and his colleagues have created the first electronic device using graphene, a component essential to wireless communication networks. (Image courtesy of Zettl Research Group, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and University of California at Berkeley.)

In This Issue

- Agriculture

- Art

- Biology

- Chemistry

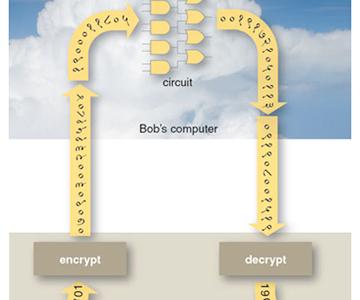

- Communications

- Computer

- Economics

- Engineering

- Evolution

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Policy

- Sociology

- Technology

Slicing a Cone for Art and Science

Daniel S. Silver

Art Mathematics

Albrecht Dürer searched for beauty with mathematics.

Graphene in High-Frequency Electronics

Keith A. Jenkins

Physics

This two-dimensional form of carbon has properties not seen in any other substance

Scientists' Nightstand

A Field Guide to Radiation

Fenella Saunders

Physics Review Scientists Nightstand

A brief review of A Field Guide to Radiation, by Wayne Biddle

The Rocks Don't Lie

David Schoonmaker

Physics Geology History Of Civilization Natural History Religion Review Scientists Nightstand

A brief review of The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah’s Flood, by David R. Montgomery