The Cost of the Wild

By Pat Lee Shipman

Restoring an ecosystem to primitive grandeur is no simple matter in a complex world.

Restoring an ecosystem to primitive grandeur is no simple matter in a complex world.

DOI: 10.1511/2012.99.454

It was a National Geographic day that I never thought I’d experience. I was in Yellowstone National Park on a course run jointly by the American Association of State Colleges and Universities and the Yellowstone Association looking at controversies surrounding the park. I expected it would be great, but I never expected what happened on our fourth day.

Some of us diehard naturalists decided to abandon our “day off” to go back to Lamar Valley in the northeast corner of Yellowstone hoping to see the grizzlies and wolves that had so far been elusive. With only about 100 wolves in the park, seeing one was a matter of good luck and knowledge. One of our excellent instructors, Brad Bulin, knew that a bison had been killed in the valley the day before and hoped we would find wolves at the carcass.

When we arrived, the wolf researchers who were already there told us that the Lamar Canyon Pack was on the carcass near dawn. They had chased off a grizzly and then killed a wolf from another pack that dared to eat from their carcass. The wolf’s body was out of sight from the road but not far away. The pack was back on the carcass, strutting and gorging, and generally feeling their power and their full bellies.

Jimmy Jones

The wolves were beautiful—some gray with black and bits of brown, a few pure black, one nearly white. Brad told us it was a strong pack formed a few years earlier by the alpha female and a pair of brothers she had teamed up with. Now they were eight strong, with at least four pups in a nearby den. The two- and three-year-old youngsters were already good hunters. They were a powerful group.

They finished eating for the moment and strolled down the slope to the river. Two young black wolves jumped into the water and others pounced on each other and played, while their elders lapped genteelly at the cool water and found comfortable places to nap.

After watching them for about half an hour, I glanced back up at the carcass, where ravens were enjoying the abundant leftovers. I focused my binoculars on something gray: a wolf. I refocused on the pack and counted: one-two-three … yes, all eight were down on the river flats. “There’s another wolf on the carcass,” I said.

One of my companions answered, “No, all eight are by the river.”

“No, look ,” I said. They looked.

Somebody asked Brad if it could be a coyote. He said, “If that’s a coyote, it’s the biggest one in history. That’s a wolf.”

Nine wolves were in sight. As we speculated on what the appearance of another wolf meant, the pack sat up, looked around and sniffed the air. They knew the ninth wolf was there.

The alpha female stood up and started to lead the pack up the slope to where the carcass lay. When the ninth wolf came into their sight, the pack broke into a run. The ninth wolf took off at top speed. Soon the pack was flat out after the stranger. It was a long chase and they moved incredibly swiftly across the slope. At one point the strange wolf had a considerable lead, and I thought it might escape. Then one of the younger pack wolves took over the role of main pursuer and slowly narrowed the gap. As he closed on the lone wolf and bit it on the rear, the drama moved to an area where the leaves of a cottonwood tree shielded the details from our view. We saw each pursuing wolf literally jump into the fray. Fur flew. Tails went up in the air. The lone wolf never came out and probably died.

Dancing and jumping, the pack celebrated its third triumph of the day. Since dawn, they had defended their kill and territory against two wolves, most likely from the adjacent Mollie’s Pack. Brad speculated that, if these loners were both from Mollie’s, losing two adults in one day might be the end of that pack as a cohesive entity. The Lamar Canyon Pack wolves returned to the bison carcass exuberantly, ate some more, and later settled down at the river’s edge to snore and rest. Life was very very good for them.

We humans were overwhelmed by what we had seen. This was the kind of event—a high-speed chase of at least ¾ mile, a pack defending its prey and its territory, a lone wolf running for its life—that casual visitors never get to see.

We watched for another half hour and thought about leaving to go to another area. Our heads were full of images and new understanding of the beauty and harshness of a wolf’s life. Watching wolves pursue and kill another wolf gave us a more realistic idea of what being a wolf means. They are more than majestic, strong, beautiful creatures, reminders of the wildness that is all too rare in our country. We were forced to face the fact that wolves not only prey on other species, they also kill their own kind, mercilessly. The reality of life is that, if they do not kill intruders, they and their pups may starve. Even in Yellowstone’s abundant ecosystem—full of bison, elk, deer, pronghorn and moose—there are not enough ungulates to allow other wolves in your territory.

Knowing how predators live and seeing it are two different things. We were quiet for a while, thinking about what we had seen.

“There’s a grizzly!” Brad cried. Probably a mile or two to the northwest, clearly visible against the green meadow, was a very large, very black grizzly bear. It was making straight for the carcass. Flicking our attention back and forth from grizzly to carcass to wolf pack, we saw the Lamar Pack sense, yet again, that an intruder was moving in. They sat up, sniffed and stared in the direction of the grizzly. The alpha female again led her pack up the hill and toward the grizzly, increasing their speed to a run. The grizzly moved relentlessly and faster toward the pack.

Who would lose or back down? Though grizzlies are usually dominant to wolves, a pack of eight was a serious opponent. Grizzly and wolves came closer and closer to each other. After a brief skirmish, the grizzly was in the middle, four wolves behind and four wolves closer to the carcass. Abruptly, the wolves decided they needed to return to their napping place by the river. The confrontation was over.

The bear loped to the carcass and spent several minutes rolling all over it, wiggling its feet in the air in a manner that can only be described as silly. It was a means of marking the carcass as his (or hers), of course. After chasing off a few impudent ravens—who returned almost immediately—the bear settled down for a meal, pulling and tugging at the dead bison. The wolves rested, their eyes closed or focused in another direction. After a surprisingly short snack, the bear walked off to rest in the shade of the trees up the hill from the carcass. It looked almost as if the main point of the bear’s visit was not to satiate hunger but to demonstrate dominance over the wolves. This might have been the very same grizzly the Lamar Pack had chased off earlier in the day.

I still replay these events in my head, unable to believe I was so lucky as to witness this drama and see so many wolves.

Wolves in Yellowstone generate controversy. Although wolves were in Yellowstone when it was first discovered, they were hunted into local extinction by European settlers. The last wolf was deliberately killed in Yellowstone in 1926. From then until 1995 there were no wolf packs in Yellowstone.

In 1995 and 1996, a total of 31 wolves from two areas in Canada were reintroduced into Yellowstone in the Lamar Valley. The idea was to rebalance the ecosystem to a 19th-century state and put more wolves into a protected area. There are now 10 packs and approximately 100 wolves in Yellowstone. The effects of reintroduction are ongoing.

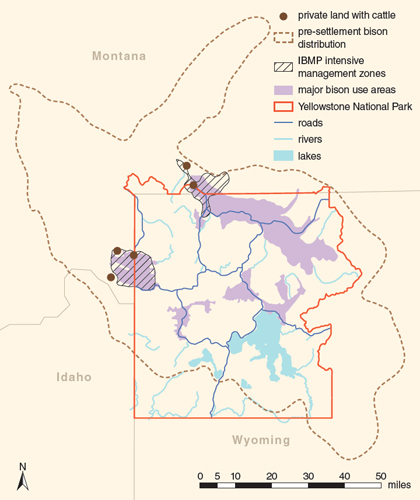

Map adapted by Barbara Aulicino from White et al. 2011.

One of the more obvious changes is a decline in the elk population. The herd also tends to stay in smaller groups than previously. Fewer elk overall means that the cottonwoods, willows and aspens along the rivers now form denser, healthier stands because their shoots are not eaten to the ground by over-abundant elk.

Beaver are increasing, damming up rivers, creating new meadows and providing new habitats for songbirds and fish. Coyotes are hard-hit by the wolves, which kill them as competitors. The coyote population has dropped precipitously, since those that are not killed tend to avoid areas with wolves. Because coyotes used to suppress fox populations, foxes are expected to be more common. All kinds of scavengers, from ravens to bears, have more carcasses to eat. Finally bison—which only a few wolf packs have learned to kill—are still growing in number but now wander outside of the park in larger numbers. Perhaps they are avoiding wolves too.

Where’s the controversy? Ask the ranchers in Paradise Valley, just outside the park, what they think of the reintroduction. “How would you feel if somebody plonked down a pack of wolves in your backyard?” they say, with good reason. Some have been on the land since the 1800s and never had a “wolf problem” before reintroduction. They fear for their children, grandchildren, pets and livestock.

These ranchers make their living by raising cattle or sheep. It is hard work but involves an independent lifestyle they love. Unfortunately, wolves do not distinguish between domestic livestock and wild ungulates, except that they may have figured out that domestic livestock are conveniently fenced in and cannot run as far. Compensation is available for ranchers who lose animals but is difficult to qualify for. You have to find the kills right away, and there has to be enough of each animal left to show the pattern of consumption typical of wolves, not some other predator.

I was told a story—possibly exaggerated—of a woman who raises sheep. One night wolves got into her pasture and killed 35 animals. Most were so thoroughly consumed she could not get compensation. Sadly, within a few days, every living ewe in that rancher’s herd aborted because of stress. She lost an entire year’s production and income.

Photograph by Doug Smith, courtesy of the National Park Service.

Wolves are also linked to bison. The Yellowstone bison herd had shrunk to a mere 25 individuals before the area was declared a park and protected. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, bison were aggressively hunted in the west, partly for food and partly as a strategy to deprive the Plains Indians—considered enemies of European settlers—of the animals that provided much of their food. Bison still have great symbolic power for the tribes.

Today, the bison herd is 3,500–4,000 individuals. The reintroduction of wolves has checked their numbers somewhat, but once a bison is full-grown it is too large for wolves or grizzlies to take. Bison leave the park in search of grazing, especially in bad winters. Paradise Valley—the same area the wolves go to—is at a lower elevation than the park and gets less snow. It is an ideal winter range for bison and for cattle.

Competition for grass and forage is not the heart of the problem; brucellosis is. Brucellosis is a bacterial disease originally found in cattle that spread long ago to the bison. The disease causes pregnant females to abort their fetuses, expelling fluids and tissues that then infect other animals in the same area. Brucellosis has been eliminated from the domestic cattle population through mandatory annual vaccinations and aggressive slaughter of all animals in an infected herd. About 45 percent of the Yellowstone bison and 5–10 percent of the elk still carry brucellosis. Vaccinating bison only at boundary facilities will probably not reduce the rate of brucellosis infection in the herd long term, but a consistent, park-wide effort would be “controversial, logistically challenging, expensive, and intrusive, with no guarantee of successfully reducing brucellosis prevalence to near zero” according to a 2011 article written by a group of Yellowstone Park rangers in Biological Conservation.

Though all female cattle are vaccinated, the vaccine is not 100 percent effective. If brucellosis is transmitted to their livestock by wildlife, ranchers face the devastating destruction of their entire herd. Further, if only two cases of brucellosis-infected cattle are discovered, the entire state loses its “brucellosis-free” status. Cattle from a state that is not brucellosis-free bring less money, and their transport across state lines is difficult and tightly regulated. The stakes are very high.

Bison straying outside the park are hazed by helicopter and by individuals on horseback or on all-terrain vehicles in an attempt to drive them back into the park. When the grazing is exhausted in the park, some bison refuse to return and face starvation. Those that remain outside the park are rounded up, penned and tested for brucellosis—very stressful events. Animals that test positive are killed. The article by the Yellowstone Park rangers attests: “About 3,100 bison were culled from the [Yellowstone] population during 1985–2000 for attempting to migrate outside the park.”

Culling a once-endangered species that is a vital component of the Yellowstone ecosystem seems wrong. It offends every conservationist’s deepest beliefs. These animals are only reoccupying their former range as circumstances demand (see map). Unfortunately, their presence in cattle-ranching areas and their infection with brucellosis pose a serious economic threat to ranchers.

Some regard the presence of bison as inevitable: “If you don’t want bison on your land, move to Ohio,” one rancher said. Others stress the inherent unfairness of endangering their carefully built herds and lifestyle with a wild animal that is supposed to be kept inside the park. They demand that a management plan be devised for the bison that will protect their herds from the risk of infection.

Bison advocates like the Buffalo Field Campaign demand that the animals be left to roam free and experience the consequences of natural selection. They emphasize that only the Yellowstone herds and those in Wind Cave National Park are free from genes resulting from crossbreeding with cattle—a strategy used by ranchers to make bison more docile.

The Yellowstone Park herds are genetically uncontaminated and have occupied their range since prehistoric times. Whatever knowledge, instincts or abilities have evolved in wild bison to help them survive in a rugged landscape with harsh winters, the Yellowstone herd has them.

Like wolves, bison also pose a danger to humans. Humans can become infected with the brucellosis bacterium, which gives them undulant fever, a very nasty, often incurable, recurrent disease. It is worth stressing that bison are not cute Disney animals; they are 2,000 pounds worth of strength, ferocity and unpredictability. While I was in Yellowstone, a tourist, who foolishly approached a bull bison much closer than park regulations allow, was gored and sent to the hospital. Bison injure more visitors to Yellowstone than bears do.

Wolves and bison are only two of the controversial issues in Yellowstone, our first and perhaps greatest national park. How can we balance the rights of the individual with those of the majority? There is a real price to pay for preserving our wild heritage. We must listen to the opinions of all the stakeholders to negotiate a just and equable solution to these complex problems.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.