This Article From Issue

January-February 2015

Volume 103, Number 1

Page 67

DOI: 10.1511/2015.112.67

UMAMI: Unlocking the Secrets of the Fifth Taste. Ole G. Mouritsen and Klavs Styrbaek. xvi + 264 pp. Columbia University Press, 2014. $34.95.

For generations, people at work in Western kitchens have tended to sort the tremendous variety of tastes available to us into four categories: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. The notion of four basic tastes goes back to the ancient Greek philosophers; it became an established principle of sensory science in 1901, when German researcher David P. Hänig published a paper describing the subjective impression of distinct tastes on different parts of the tongue. That work inspired the theory that our favorite dishes and drinks—from a sweet, smoky barbecue sauce to a tangy margarita in a salt-rimmed glass—all derive their appeal from ingenious combinations of these basic tastes.

The theory has turned out to be incomplete, however. At almost the same time that Hänig published his work, Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda demonstrated the existence of a fifth taste, which he named umami (from the term umai, for “delicious”). Ikeda identified one part of the chemical basis for umami as glutamic acid and its salts (glutamate), but Western scientists were slow to agree that this substance produces a distinct taste on the tongue. Only in 2000, when researchers found receptor molecules in taste buds that responded specifically to glutamate, did umami gain worldwide recognition.

From Umami

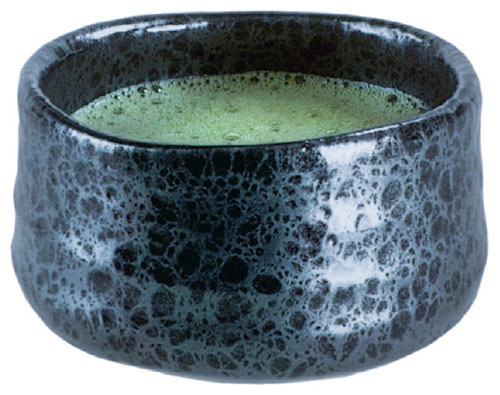

Ironically, this fifth taste has played a vivid role in Western food all along—we just didn’t have a word for it. In Umami: Unlocking the Secrets of the Fifth Taste, Ole G. Mouritsen, a biophysicist, and Klavs Styrbaek, an experienced chef, have given us a book that not only defines umami but explains how best to bring out this taste in a wide variety of dishes. Most important, they reveal that the full power of umami comes from the synergy between glutamic acid and a ribonucleotide (a chemical compound containing ribose plus one base and one or more phosphate groups). As it turns out, the food additive monosodium glutamate, or MSG, once considered all-powerful in Western renditions of Asian cuisine, is almost flavorless in its pure granular form, because the glutamate ions released in food produce very little taste on their own. The fullest effects of umami come from combining the glutamic ingredient with a ribonucleotide like the inosinate in beef soup, the guanylate in dried shiitake mushrooms, or the adenylate in scallops.

Mouritsen and Styrbaek have each published previous books on food, and their enthusiasm for the fifth taste comes through vividly in this new volume. (Umami is Mouritsen’s third book on the science of cooking. His Seaweeds: Edible, Available, and Sustainable was excerpted in the November–December 2013 issue of American Scientist.) Together, the scientist and the chef aim to raise awareness of the sensory possibilities of umami by “taking advantage of the gustatory synergy produced by combining different ingredients.”

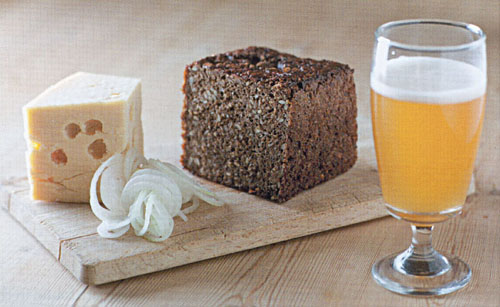

Those of us with less adventurous palates (a.k.a. “picky eaters”) may wonder whether the synergistic principle of umami, so deeply rooted in Japanese culture, can really apply to ingredients found in other parts of the world. Mouritsen and Styrbaek show that it can, transplanting the concept of umami to the bracing environment of new Nordic cuisine by creating recipes based on the food resources of mainland Denmark and the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland: a rich array of fish and shellfish, seaweeds, mushrooms, smoked meats, and dairy products.

From Umami

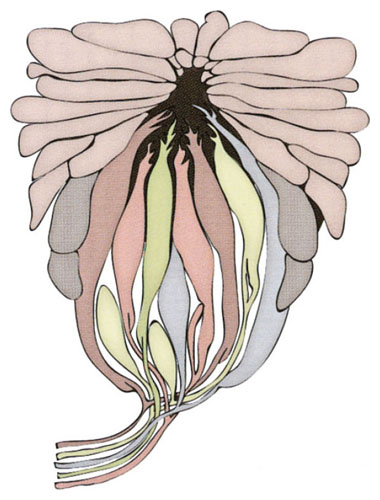

The authors draw on gastronomic and scientific literature to explore the neural basis for the complicated set of perceptions that we call taste, using crisp illustrations and medical images to explain the action of umami on receptor cells in taste buds located all across the tongue. Then comes a smorgasbord of tips on the preparation, uses, and even the folklore of umami-rich foods, distributed into three chapters according to their sources: umami from the sea (found in seaweeds, fish, and shellfish), from the land (fungi and plants), and from land animals (meat, eggs, and dairy). Interspersed throughout the book are short sections that provide interesting sidelights, for example, one demystifying the medical condition known as “Chinese restaurant syndrome,” and another deconstructing the powerful umami kick of the British sandwich spreads Bovril and Marmite and their Australian cousin, Vegemite.

There is plenty of material here for readers who may approach this book from a perspective more culinary than chemical. Abundant photography by Mouritsen’s son, Jonas Drotner Mouritsen, shows preparations of food in ways that are beautiful, informative, or appetizing—and often all three at once. The book also contains 39 umami-themed recipes, which run the gamut from basic (potato water dashi, the traditional Japanese soup stock) to elaborate (white chocolate cream, black sesame seeds, Roquefort, and brioche with nutritional yeast), crisscrossing categories of traditional Western cuisine without missing a beat.

From Umami

An engaging read, lucidly translated and adapted from the original Danish edition by Mariela Johansen, Umami is at once a scientific treatise, cultural history, unique collection of recipes, and handsome coffee-table—or, for that matter, kitchen-table—book.

Sandra J. Ackerman is senior editor of American Scientist. Her most recent book, Hard Science, Hard Choices: Fact, Ethics, and Policies Guiding Brain Science Today, was published in 2006 by Dana Press.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.