Taking the Long View on Sexism in Science

By Pat Lee Shipman

I am one of the many women who exited academic science. Decades later, too many others are still leaving for the same reasons.

I am one of the many women who exited academic science. Decades later, too many others are still leaving for the same reasons.

DOI: 10.1511/2015.117.392

My first lesson in the harmful power of sexual innuendo and stereotype was when I was a new PhD in the late 1970s. I wrote a manuscript for a book based on my thesis, an analysis of fossil animals in Kenya. A major academic publisher turned it down because it was “too controversial.” Stunned that this analysis could be seen as controversial, I pressed the editor for specifics. Eventually, he admitted that one reviewer had said that I could only have been awarded a PhD if I had slept with my committee.

Thinking of the one married and two unmarried straight men, the two gay men, and the bisexual man that comprised my committee, I decided this assertion was best challenged directly. I was confident my work was good. So I invited the editor to call my committee members and ask them. A long silence followed, in which I supposed the editor was blushing at the mere thought of asking these scholars such an insulting question. To my surprise, the editor admitted that he had done just that. Taken aback, I asked him what they had said. “They said there was no truth in the allegation,” he replied, but he still would not accept the manuscript.

Nevertheless, Harvard University Press did accept the book, Life History of a Fossil , which became a classic in its field. I wrote of this episode and others in a 1995 column for American Scientist.

After that column appeared, right up until my retirement in 2010, there were many more episodes of a similar flavor. Once, a younger collaborator of mine and I applied for the same job. At that point, all my collaborator’s publications were coauthored with me, except his PhD thesis. I had a number of independent papers, including a single-authored note in Nature and a book. I did not make the short list but he was hired.

A few years later, I discovered by accident that I was the lowest paid associate professor in my institution—the same year I began working as an assistant dean. My underpayment was so pronounced that the dean of the entire institution told my chair to give me an immediate 20 percent raise. A friend in administration, congratulating me, said she had once overheard my chair remark that he didn’t need to give me a raise because my husband was well paid.

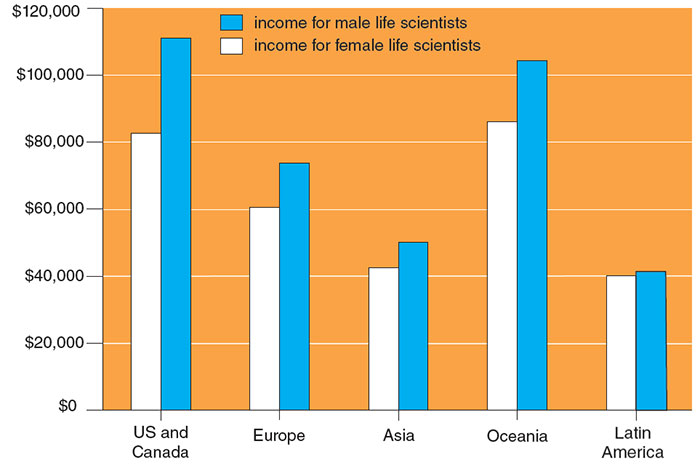

Justin H. Storms

Because of these and other experiences that eroded my trust in senior colleagues and in the institution of academic science as a place where my research could flourish, I quit and never again held a standard academic appointment. My story is all too typical, full of the kinds of problems that contribute to the “leaky pipeline” that lies between women in science and senior positions. In 1977, the number of women entering graduate school in anthropology equaled the number of men, but not until 1986 did the number of women receiving PhDs in anthropology equal the number of men, according to anthropologist Eli Thorkelson, who studies university culture. According to a 2013 report by the National Science Foundation, female trainees in science now slightly outnumber male trainees, but among the ranks of full professors they constitute only about 20 percent. There is some evidence of progress. According to data summarized in the Life Sciences Salary Survey of 2014, female assistant professors are now paid slightly more than their male counterparts, and at the associate professor level women earn almost as much as men. At full professor rank, however, females on average earn only 89 percent as much as males.

I have had a productive career on the fringe and have continued to research, write, and publish—but I gave up most of my opportunity to pass my knowledge and enthusiasm directly to students, not to mention forfeiting years of salary.

A recent sensational case of sexist behavior that epitomizes the general lack of awareness among elite scientists occurred back in June, when Sir Tim Hunt, Nobel laureate and fellow of the Royal Society, made this now infamous remark at the World Conference of Science Journalists in Seoul, South Korea: “Let me tell you about my trouble with girls … Three things happen when they are in the lab: You fall in love with them, they fall in love with you, and when you criticize them, they cry.” He then suggested that male and female scientists distract each other and should work in separate laboratories.

The ensuing public outcry and swift call for his resignation from an honorary appointment at University College, London, as well as several advisory committees, seemed to shock and bewilder Hunt. The inflammatory remarks were intended to be jocular, he told Robin McKie of The Guardian, a claim still being echoed by some of his defenders.

Despite what Hunt and others considered a joke, there was a deep seriousness to his comment. Hunt has been supportive of women entering science, but not of their rising to the top. For example, in an interview with Labtimes in 2014, Hunt said that he was unsure why there was a “staggering” inequality in the numbers of males and females in the upper echelons of science. “One should start asking why women being underrepresented in senior positions is such a big problem,” he said. “Is this actually a bad thing? It is not immediately obvious for me.... Is this bad for women? Or bad for science? Or bad for society? I don’t know, it clearly upsets people a lot.” This kind of obliviousness to the real hurdles women face propagates the culture that excludes them from the top levels of power, prestige, and pay.

Justin H. Storms

Some women treated the Hunt episode as an opportunity to move forward. Using a hashtag, a label that links conversations about the same topic on social media sites, to pull their voices together, women expressed their dissent. Under the label #DistractinglySexy, women scientists from a wide range of specialties posted photographs of themselves in normal working attire, wearing lab coats, hazmat suits, or grimy field clothes. There was backlash against such protests as a number of prominent scientists, most famously Richard Dawkins, declared that Tim Hunt had been treated unfairly. I argue that when sexism looks so normal that we don’t even see it—despite the experiences I and my colleagues have endured—it is no joking matter.

There is a still darker side to the discrimination. A few months before this episode, Michael Eisen, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, sat next to Hunt in a session about obstacles to women’s careers at a meeting for young investigators in India. Eisen wrote on his blog:

It is unconscionable that, barely a month after listening to a woman moved to tears as she recounted a sexual assault from a senior colleague and how hard it was for her to regain her career, Hunt would choose to mock women in science as teary love interests…. That a person as smart as Hunt could go his entire career without realizing that a Nobel Prize winner deriding women—even in a joking way—is bad just serves to show how far we have to go.

This young woman is far from alone. A colleague who is a dean of students in the United Kingdom told me that one of her students, a young woman, had tearfully recounted being raped by a senior colleague. When I held a similar position in the United States, I listened to a female student whose male adviser had rigged a camera on his shoe to take photographs up her skirt and had booked double rooms for them at conferences where she was presenting her work. Although she was deeply troubled, she begged me not to report the incident officially. She was afraid of losing his support for further training.

Rape may seem like a rare and extreme problem, but in truth it is not so rare and is part of a continuum of sexual harassment. According to a survey published last year, sexual harassment is a common experience for anthropologists, particularly during fieldwork. Out of 644 respondents to their survey, 70 percent of females experienced harassment and 26 percent reported sexual assault. Of male respondents, only 40 percent reported sexual harassment and 6 percent reported assault, a statistically significant difference. Almost half of the harassers and half of the assaulters on women were professionals who had authority over the women. In significant contrast, males reported far more peer harassment (53 percent versus 27 percent harassment from superiors) and assault (50 percent were peers versus 25 percent superiors). This kind of survey is unique, so the rates for other fields are unknown.

I find it tragic that men can rise to the top tiers of science and remain completely unaware of the experiences that keep equally talented women from joining their ranks.

I can say without fear of contradiction that I was neither the first nor will I be the last woman to leave academia because of sexual discrimination. Many women scientists of my generation have had similar experiences and some have suffered worse, including outright assault.

The culture of discrimination is far-reaching and ongoing. This year I learned of two public instances of overt sexual harassment directed at junior women that took place at a professional anthropology meeting in April. The accounts became a major topic of discussion in anthropology circles, so much so that I was able to check the stories with both subjects as well as with others who had witnessed the incidents. In one case, a senior male in the field apparently believed commenting on a junior colleague’s breasts was acceptable behavior and possibly even flattering. In the other, a senior male researcher invited a junior female colleague to sit on his lap.

Even for women writing on behalf of major institutions, taking a clear stance against the culture of harassment is difficult. On June 1, Science published a query from a woman scientist asking for advice on interacting with her mentor and boss, who consistently stared at her breasts and tried to look down her shirt.

Senior scientist and former American Association for the Advancement of Science president Alice Huang suggested the writer put up with being ogled “with good humor if possible,” because her mentor’s actions were neither illegal nor actionable but a common human behavior. She concluded: “Just make sure that he is listening to you and your ideas, taking in the results you are presenting, and taking your science seriously. His attention on your chest may be unwelcome, but you need his attention on your science and his best advice.” The echoes of the student I listened to are unmistakable.

Science rapidly removed this exchange from its website “because it did not meet our editorial standards and was inconsistent with our extensive institutional efforts to promote the role of women in science.” I like to think they also removed it because it contained bad advice. Accepting overt sexism in the workplace without comment only serves to propagate it.

The gender gap in pay for senior positions has by no means closed, but greater equality is making its way up the ranks. Nancy Hopkins, a biologist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was one of a group of faculty who brought the evidence of pervasive discrimination against women to the administration’s attention in 1999. In a recent article in DNA and Cell Biology, s he refers to the gains in equality as “extraordinary,” saying:

To increase the number of women faculty requires oversight at a level above individual departments because of the slow rate of faculty turnover and the small number of faculty hired each year. If you stop tracking data and preventing inequities in hiring or distribution of resources and compensations, progress stops and may even retrogress.

The quick reactions to Hunt and Huang indicate progress—albeit of a reactive nature. But as long as the leadership in science is so overwhelmingly oblivious to discrimination, the fight to root out conscious and unconscious bias against women will continue.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.