This Article From Issue

July-August 2007

Volume 95, Number 4

Page 364

DOI: 10.1511/2007.66.364

Music: A Mathematical Offering. David J. Benson. xiv + 411 pp. Cambridge University Press, 2007. $48.

"Music is a science," wrote the great composer and theorist Jean-Philippe Rameau in 1722, "which should have definite rules; these rules should be drawn from an evident principle; and this principle cannot really be known to us without the aid of mathematics." David J. Benson's book Music: A Mathematical Offering gives the latest and fullest view of music in the light of mathematics. A professor of mathematics at the University of Aberdeen as well as a keen amateur singer, Benson has assembled a fascinating variety of topics that make his book a uniquely rich source, whether for classroom use, reference or self-study. He has constructed the different sections that flow from his general introduction to be independent, allowing readers to follow their own interests and predilections.

From Music.

This book goes into mathematical details that many general accounts avoid, and here Benson deserves special praise for his skill and clarity. He does expect his readers to be familiar with standard college calculus, but he always presents his arguments with enough helpful explanation, good examples and exercises to put his audience at ease. Some sections do go into more depth (including a few references to complex variables), but the reader can skip them if so inclined.

Benson begins with the physics of sound, not neglecting the perceptual subtleties of human hearing, which he outlines clearly. After covering the basics of vibrating strings and their wave motions, he turns to a nice exposition of Fourier's theory of harmonic analysis, readily accessible to someone who has studied basic calculus.

Having developed these tools for his readers, Benson uses them to provide a mathematician's guide to the orchestra, discussing characteristic instrumental timbres in terms of their harmonic spectra. These considerations also allow him to present consonance and dissonance from the point of view of the overtone spectrum and to include more-modern conceptions of bandwidth. I was especially struck by his presentation of artificial spectra (such as those produced by synthesizers), which seems to shatter many hoary preconceptions, including the separation of consonance from dissonance: It turns out that by manufacturing a tone with artificially adjusted partials, one can make almost any set of intervals seem consonant.

With this thorough and surprising survey under their belts, readers are able to appreciate the fresh look Benson then takes at the ancient questions of scale construction. He covers these deftly from the Greeks through Harry Partch and Wendy Carlos, up to such recent examples as the thirteen-tone Bohlen-Pierce scale of 1989. A plethora of examples are provided along the way, some drawing on African and Asian music. He includes the harmonic implications of these various scales, along with the challenges they have posed for instrument builders, always returning to the mathematical problems that generated them. For instance, questions of consonance and interconnection of scales lead him to show them as continued fractions (both elegant and simple), as "wrapped" around cylinders or other shapes, and as lattices. Throughout, Benson offers many excellent suggestions for further listening as well as reading, giving his book an aural dimension that adds greatly to its interest.

Benson's modern approach gives him a natural way to include the possibilities and problems of digital music, presently all-pervasive in CD and computer formats. Here the classic topics of Fourier analysis lead to current questions of bandwidth and sampling (crucial in all the digitized music we hear). Once only an experimental concern of computer-music pioneers, questions of digital synthesis now are inescapable. Benson presents such important developments as John Chowning's seminal innovations in the synthesis of electronic sound. By making an ingenious extension of the idea used in FM radio, Chowning showed how to synthesize digital sounds far richer than those restricted to simple combinations of sine waves.

In these chapters, as at several places in the book, Benson may provide more information than one really wants to know, but such sections can be skimmed for the general picture or even skipped altogether. He also goes into considerable detail about some significant computer programs in this area, such as CSound, a public-domain synthesis program. Anyone who has struggled to figure out what the devil MIDI, MP3, WAV and other such formats and acronyms are really about will find his explanation quite helpful.

From Music.

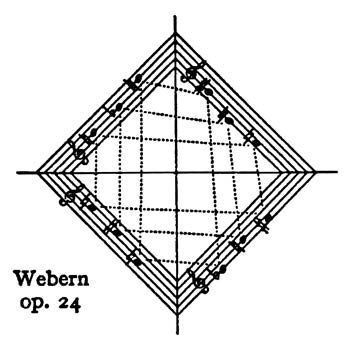

Benson concludes with an illuminating and intriguing account of symmetry in music. Beginning with basic applications of inversion and reflection (such as those J. S. Bach used so masterfully), he outlines group theory, offering a well-chosen and diverse set of examples (including Guillaume de Machaut, Arnold Schoenberg and P. D. Q. Bach) from many periods of music. Benson does not presume any familiarity with this more abstract theory but artfully and clearly builds it up from his examples. Using a clever quote from Dorothy Sayers's The Nine Tailors, he describes change ringing—the English art of ringing heavy church bells in sequence—as a way to lead us to Cayley's theorem, so fundamental to group theory. Similarly, the equivalence between the arithmetic of clocks and the twelve-tone chromatic scale leads neatly to cosets and quotient groups. The concerns of modern music theorists and mathematicians converge with a vengeance in such topics as pitch class sets. In other examples, Benson indicates that Anton Webern's Concerto, op. 24, uses a dihedral group (his intriguing diagram bends Webern's score into a square) and shows that Olivier Messiaen's motoric piano piece Ile de Feu 2 implicitly uses the formidable permutations of the Mathieu group M 12 (which has no fewer than 95,040 elements).

Perhaps our children will one day remark on the group symmetries in their favorite music in the way that we now simply note a beautiful tune. They, no less than we, will have much to learn from this delightful book, which sets a new standard of excellence and inclusiveness. Anyone who knows some college-level mathematics and is curious about how it can illuminate music will be richly rewarded by reading Benson's outstanding book.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.