Getting to the Heart with AI

By Akilah Abdulraheem

Deep learning programs may be able to examine data from a common medical test to flag patients with undiagnosed cardiac disease.

Deep learning programs may be able to examine data from a common medical test to flag patients with undiagnosed cardiac disease.

A patient with serious heart disease might go without noticeable symptoms for a long time. If, for instance, they have a heart valve that isn’t opening or closing properly, they might start getting fluid buildup in their lungs that will only very gradually affect their breathing, among other problems. Frequently, these patients end up as severe cases before they even know they are developing heart disease. “All of us who work in medicine have seen too many cases to count of patients who have ignored their symptoms,” says Timothy Poterucha, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. “They just brushed off their shortness of breath, or they would go to sleep and hope their chest pain would go away.” Now, Poterucha and his colleagues are researching how the data analysis abilities of certain types of artificial intelligence might help them use a common medical exam to get around this problem and diagnose more heart disease patients sooner. “You can only treat the patients you know about,” Poterucha says.

Kjetil Lenes, Oslo, Norway/Wikimedia Commons; Korawig Boonsua/Alamy Images; Blackeyelion/Wikimedia Commons

The team is currently working on a system for diagnosing structural heart disease, an umbrella term for any physical ailment related to the heart’s valves, chambers, or muscles that makes the heart have to work harder to pump blood. “The heart has four valves, and their job is to control the flow of blood through the heart,” Poterucha says. “If they become leaky or narrow over time, that can cause more and more strain on the heart. This strain starts off without patients feeling it, but as the disease gets more severe, the patients can get short of breath, they get heart failure, and they can die.”

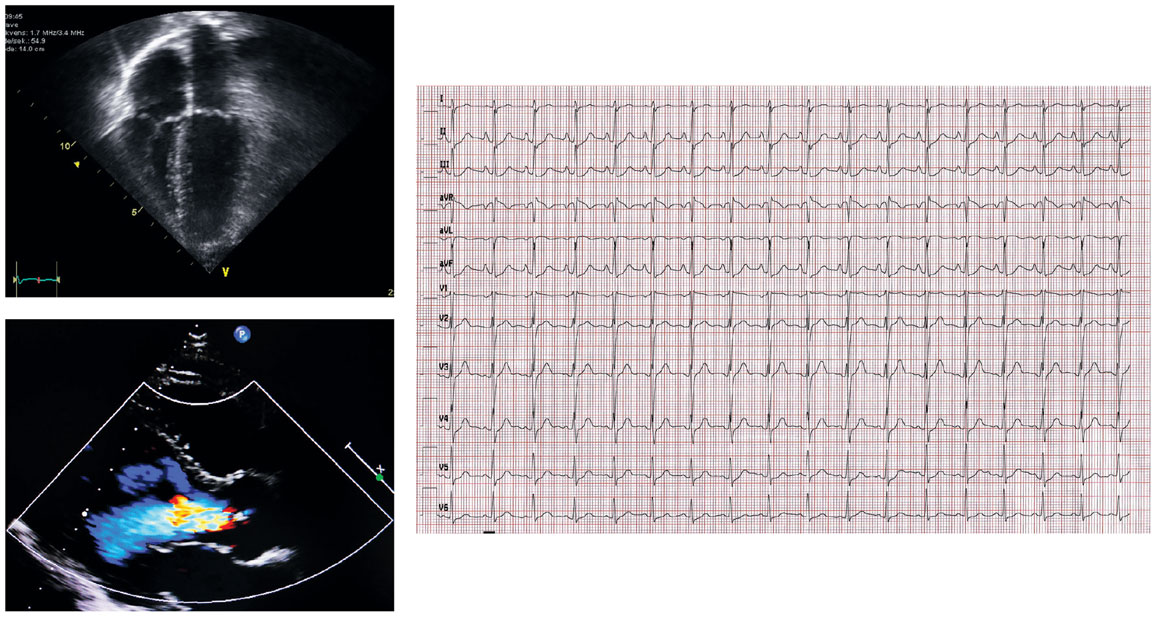

Diagnosing structural heart disease requires an echocardiogram—an ultrasound image of the heart and its blood flow. But that test is more expensive so fewer people receive it until they have developed more severe disease. A much more common test is the electrocardiogram (ECG)—the series of blips from heart electrical activity as it contracts, opens valves, and moves blood around. “There could be as many as several hundred million ECGs done in the world every year,” Poterucha says. “They can be done anywhere with almost no training, and they are inexpensive as far as medical tests go, so that gives it an enormous advantage.” Poterucha and his colleagues had already been working with AI deep learning models for other types of heart disease, so they wanted to see if they could train an AI neural network to take data from ECGs and predict which patients might be at high risk for structural heart disease and therefore should be recommended for an echocardiogram.

As the team recently reported in Nature, they were able to collect patient tests from an eight-hospital system in New York City, taken over a span of 15 years. They used only records of patients who’d had an echocardiogram taken within a year after an ECG. This criteria gave them a set of almost 800,000 records to train their model, a further set of about 35,000 records to validate the AI’s training, and then a set of almost 45,000 patient records for testing the model. The model was trained on a number of traits in echocardiograms that can indicate structural heart disease, including the heart’s pumping function, the thickness of the heart’s walls, the presence of high pressure within the heart, and evidence that the heart valves have disease. The model was then trained on each patient’s associated ECGs; the researchers directed the AI to look at the amplitude, duration, and interval of different segments of the waves, and to extract traits that the AI learned could indicate the presence of structural heart disease. After working through the training and validation sets, the model, called EchoNext, was able to identify patients in the test set who were at high risk for structural heart disease with an accuracy of 77 percent, using only ECGs. A subsequent test on data from other hospital systems produced similar results.

To further validate the model, the team created a subset of 150 ECGs and asked a group of cardiologists to diagnose them for structural heart disease. The cardiologists’ accuracy was 64 percent, and 69 percent when they were also given the AI score. “There are some signals we can look at as cardiologists that can indicate if a particular ECG is likely to be from a patient with structural heart disease,” Poterucha says. “But it’s kind of a challenging task that we don’t train ourselves exactly for.” Poterucha also notes that, in practice, a doctor will have far more information with which to make a diagnosis. “When I see a patient, I am able to take their history, find out their symptoms, look at their past medical records and prior testing, do a physical exam and listen for murmurs or find signs of heart failure with swelling in their legs, fluid in their lungs—and then I look at their ECG,” he says. “The actual clinical implementation will be a cardiologist with lots of information who has the assistance of an AI model.”

Poterucha hopes that these systems will help catch patients who do not have a lot of follow-up care, and will help decrease the amount of time doctors need to make a diagnosis or recommend further testing. The system is currently undergoing clinical trials in a series of urban emergency rooms, in which patients are often not well connected to routine medical care. “Our goal is to try to look at every single ECG done in every single patient in all the hospitals that this study is being conducted at, and find those patients who are mostly likely to have undiagnosed structural heart disease, and then we can go on and test them, find the disease, and then do something about it,” Poterucha says. “We need to set up our health care system in such a way that we try to improve care overall for everyone, with a particular focus on the patients who get the least medical care.”

The term AI can have mixed connotations for many people, but so far, Poterucha says that patient response to the technology has been positive. In a separate, previous trial, Poterucha and his colleagues used AI to identify a different form of heart disease. They would cold-call patients, which Poterucha admits could be disconcerting, but he says most patients were appreciative. “It’s an unusual call for a patient to get, when we call them and say, ‘Hi, we’ve built an AI system that analyzed your ECG and your echocardiogram, and we think you might be at risk of having this particular health condition; would be interested in coming in for testing?’ But we found that patients tend to be grateful that someone thought it was worthwhile to go the extra mile to build a system to detect the disease, and they’re glad that we can do something about it.”

Patients will not be visiting AI doctors anytime soon, but Poterucha and his team think that these tools will help busy medical systems better handle large amounts of data and high patient loads, and be more proactive in diagnosing patients earlier, when they can be more effectively treated. As Poterucha notes: “We can use the ability of humans to take a very comprehensive history and look at a lot of data, and focused AI models which are very good for one particular task, and we can pick out a way to combine those strengths into doing the best possible job we can to detect heart disease.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.