Guideposts for Regeneration

By Cyrille Teforlack

Specialized flatworm cells turn on position genes to direct when and where repairs happen after an injury.

Specialized flatworm cells turn on position genes to direct when and where repairs happen after an injury.

The waves crash on the shore, turning the sand a dark brown. A massive, serpentlike beast looms over Hercules, its multiple heads thrashing and ready to strike. Hercules swings his sword, slicing through the beast and watching as one of its heads falls to the ground. He steps back, preparing to strike once more. But his success is short-lived: From the wound, two new heads emerge, each one angrier than the last.

The regenerative powers of the Hydra have been a mythical symbol of resilience for centuries. But the ability to grow back severed body parts exists across countless species, some with a capacity bordering on the unbelievable. Salamanders, for instance, are capable of regrowing limbs in mere weeks, and zebrafish can repair damaged hearts. Even humans possess limited regenerative abilities: The liver can heal large portions of itself after a severe injury. But no animal embodies the marvel of regeneration quite like the flatworm.

Salah Ayoub, BIMSB/MDC and Jordi Solana, BIMSB/MDC/Oxford Brookes University

Flatworms encompass a wide array of species, but one especially intriguing group is the planarians. These worms are found in various habitats, largely in freshwater and saltwater, but some have also adapted to land. They also range widely in size: Bipalium kewense, a terrestrial planarian from South America, can reach up to 25 centimeters in length, whereas others measure just a few millimeters—barely longer than a fingernail. But all planarians share a powerful ability: Cut one into pieces, and within a week, each fragment will regenerate into a fully formed, genetically identical clone of the original.

This ability is enabled by a special type of stem cell called a neoblast, which makes up about 20 percent of all the cells in the worm’s body and is its only dividing cell type. These cells can transform into any of the worm’s more than 120 different cell types, including more neoblasts—an ability that’s called pluripotency—which allows them to rebuild missing tissues.

The remarkable regenerative abilities of planarians have fascinated scientists for more than a century. In the late 1800s, American evolutionary biologist Thomas Hunt Morgan documented how fragments could regenerate into complete worms. And before Morgan, Charles Darwin collected planarians during his travels, marveling at their adaptations and striking color patterns.

Despite this extensive study, key questions remain: How do neoblasts determine the types of cells they will become? How do they tell their location in the body and navigate to where they’re needed? Interested in uncovering the answers to these and many other questions, biologist Peter Reddien of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and his team began looking at one freshwater planarian species, Schmidtea mediterranea, which is characterized by cartoonlike eyespots at the top of the anterior tip of its body. “There are a lot of good organisms for studying regeneration,“ Reddien says. “But planarians are some of the world’s best regenerative organisms, and they have tissues similar to those found across bilaterally symmetrical animals, from musculature to nervous system, skin, intestine, and other tissue types. So they are a good model for studying the regeneration of widely seen cell types in animals.”

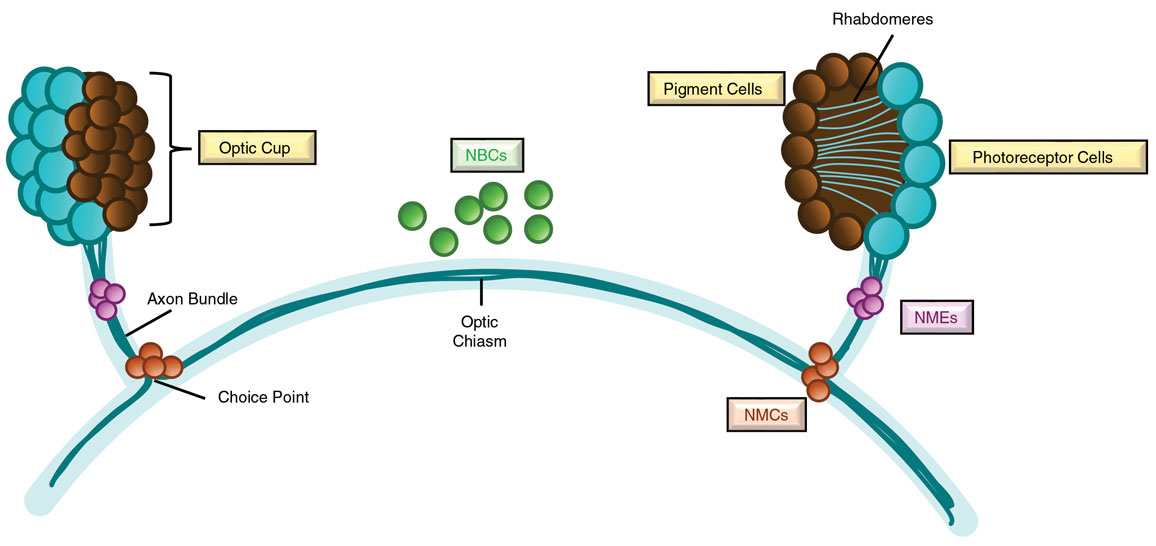

To understand how cells recreate specific missing tissues, Reddien and his team started with one of the simplest organs in the planarian body, the eyes. Planarian eyes are composed of just two main cell types: pigment cells, which cluster together to form a light- focusing structure called an optic cup, and photoreceptor cells, which detect light and guide the worm’s movement. Each photoreceptor cell extends specialized projections called rhabdomeres into the optic cups, akin to rods and cones in the human eye. Their nerve fibers, or axons, must navigate precise pathways within the worm’s body: Some extend down and back to connect with the brain, whereas others project contralaterally, reaching toward the opposite eye and splitting off at a region called the choice point. This wiring enables the worm to integrate light signals from both eyes and navigate its environment. Through a behavior known as phototaxis, planarians move away from light toward shaded areas, avoiding open water where they are vulnerable to predators.

Cyrille Teforlack

These small organs contain complex neuronal connections and trajectories that must be precisely assembled both during their initial formation and after injury. During development, many animals have cells that serve as “guideposts” to direct pioneering neurons toward their targets. Then, once their connections are made and other axons follow the existing tracts, the guidepost cells become dispensable and are lost. Therefore, in the adult animal, if the system is damaged, there are no guidepost cells present to steer regenerating axons to the correct locations. Reddien began to speculate about what might allow regeneration to occur so readily in the planarian visual system. “Guidepost cells are like the scaffolding around a building,” he explains. “But if you injure the system, what are you going to do if the scaffolding is not there anymore? What we began to wonder is: What if part of the solution is the retention of guidepost cells into the adult stage, such that the scaffolding would still be there? Then, the guideposts could still instruct the regeneration of the nervous system. That’s what we began to investigate.”

Reddien and his team suspected that specialized cells retained near the planarian eye might serve as these guideposts, steering regenerating photoreceptor axons toward their targets. To find these cells, they turned to a method called fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH), which uses glowing probes made from synthesized messenger RNA (mRNA) to latch onto specific genetic sequences in the worm’s body. When hit with a focused laser under a microscope, the probe lights up, allowing researchers to visualize specific cells based on the mRNA they express. This technique provided the Reddien lab members with their first observation of a few small cells near planarian eyes. “A staff scientist in the lab, Lucila Scimone, noticed a tiny number of muscle cells right next to the eyes of planarians, and that was curious: They’re not part of the eye, seemingly, and there’s just one or two right next to both eyes,” Reddien explains. “We had our suspicions that they would be performing some kind of regulatory function, because we found in prior work that the muscle in planarians is the source of instructions guiding processes of regeneration.”

The team found that the tiny cell clusters expressed two genes, called notum and frizzled 5/8-4, which are known for their role in establishing body position—information that is a hallmark of development and regeneration in all animals. During development, cells throughout the body express such position control genes (PCGs) in patterns that inform the surrounding cells about their location and the type of cell they should become. These genes are also important after injury in planarians. For example, notum expression has been shown to stimulate head regeneration in wounds that are anterior-facing. Another gene, called smedbmp4-1, is required for correct regeneration at the body’s midline and for maintaining the back-belly axis of the animal. When cells expressing these PCGs are lost, remaining cells change their gene expression to restore such positional identities, ultimately guiding correct anatomical position during regeneration. Highly regenerative vertebrates such as axolotls that can regrow appendages after injury will typically express PCGs in cells of the connective tissues of the limb. Similarly, Reddien’s lab found that, in worms, PCG expression took place in muscle cells throughout the body, with a tiny subset that seemed to be localized to the eye. “We found this system of positional information in planarians was harbored in the musculature and functions as its connective tissue, an intriguing connection between regeneration in vertebrates and planarians,” Reddien says. “The whole blueprint for the locations of where things should be in the animal is determined by gene expression patterns in the muscle. It’s incredibly beautiful.”

These guidepost muscle cells appeared in three distinct locations in the visual system: near the eyes (called NMEs, for notum-expressing muscle cells near the eye), at the two choice points (called NMCs, for notum-expressing muscle cells at the choice points), and at the midline where axons cross between brain hemispheres (called NBCs, for notum-expressing brain cells). “When Lucila showed me pictures of these cells, we easily could have moved on and not studied them, because we didn’t have the idea of what they did at the beginning,” Reddien recounts. “But they were so odd that we couldn’t help but think, ‘There’s got to be something here; maybe we should look into these!’”

To test the role of guidepost cells in regeneration, the team surgically removed a single eye and its associated axons up to the choice points, and then observed what happened. Within days, new axons sprouted from the regenerating eye and reached toward the existing uninjured eye. Taking a deeper look, the researchers also noticed that the trajectories of the regenerating axons seemed to align with the position of the different guidepost cell populations of the uninjured circuitry—suggesting these cells were acting as a signal to turn the axons in the correct direction, similar to their function in other parts of the body to maintain the worm’s anatomy. “One of the key things that we noticed was that there was a little variability in the exact position of the guidepost cells, and there was a little variability in the exact position of the axons,” Reddien explains. “We’d even occasionally see a stray axon—when we looked at the axons and the guidepost cells together, wherever the guidepost cell was, even if it was a little out of position, that’s where the axons were.”

Then came a bigger test: What happens when the entire visual system is destroyed? The team decapitated the worms, forcing them to rebuild both eyes and brain. Remarkably, the process unfolded like clockwork. One day after amputation, eye cells began to form. The next day, axons emerged and bundled near the newly formed NMEs that help to organize their path. By day three, NBCs appeared at the midline, guiding axons from both eyes toward one another before they projected into the regenerating brain. These guidepost cells, the researchers think, function like a tracking system— helping the regenerating axons navigate the complex terrain to reconnect the visual circuit. As the team recently reported in the journal PLOS Genetics, they have also found that photoreceptor neurons interact with the brain’s glial cells to support their regeneration.

The mythical Hydra’s ability to regrow two heads for every one lost is a thing of fantasy, but the planarian’s story is real and unfolding under the microscope. Although flatworms may seem like obscure lab animals, understanding how they rebuild entire organs could one day help us coax human stem cells to regrow tissues lost to injury or disease. Reddien thinks that learning about how guidepost cells function in nervous system regeneration may have applications in human regenerative medicine. “A lot of the molecules we’ve found are conserved in humans,” he says. “As we’re finding mechanistic concepts of regeneration like the importance of a guidepost cell for neural wiring, one can think about engineering applications with this type of knowledge.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.