Fossils Saved by Fool’s Gold

By Fenella Saunders

Mineralized animal remains from millions of years ago reveals new species.

Mineralized animal remains from millions of years ago reveals new species.

The glint of the mineral known as fool’s gold used to be a blow for miners searching for the real thing. But for fossil hunters, this glimmering mineral, iron pyrite, is a priceless treasure. Under the right conditions, an organism’s remains can be mineralized in pyrite, creating a fossil that is remarkably detailed and durable, providing evidence of extinct animal anatomy that is rarely preserved. A new pyrite fossil discovery, combined with advanced imaging techniques, has identified a previously undiscovered species that could help elucidate the evolution of arthropods, particularly the head appendages and mouthparts of horseshoe crabs and trilobites.

Luke Parry, Yu Liu, and Ruixin Ran. From Current Biology 34: P5578.

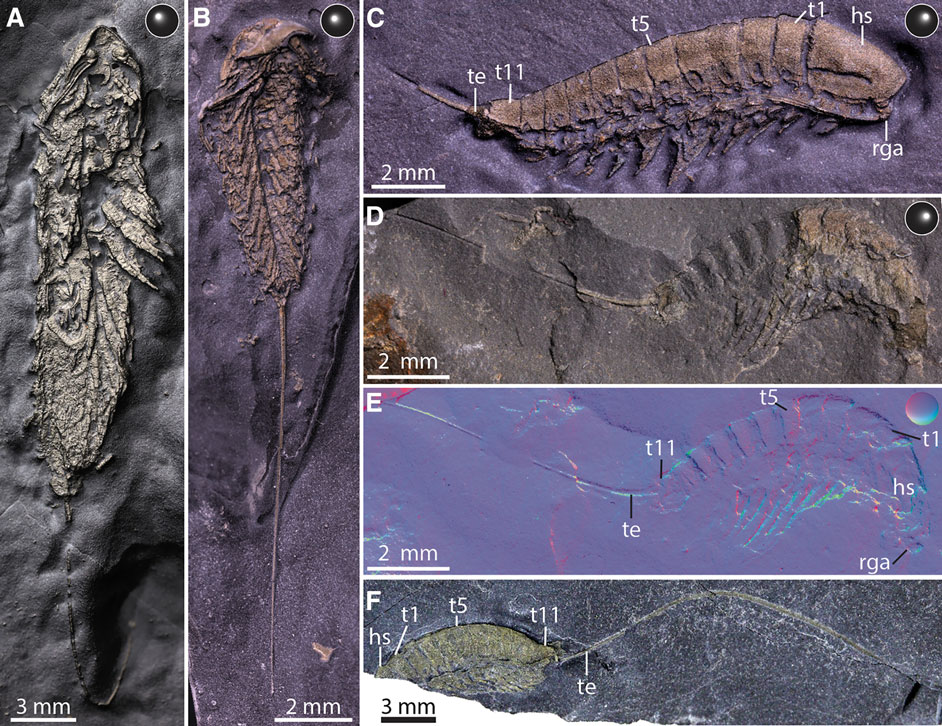

The set of five shimmering fossils was found in New York State at a famous site called Beecher’s Trilobite Bed. The ocean floor there at the time these creatures died was low-oxygen and iron-rich, allowing for fast mineralization of the delicate tissues of these organisms. Sulfate-reducing bacteria break down organic material in these low-oxygen environments, producing hydrogen sulfide. This compound then reacts with iron to produce iron sulfide, or pyrite. Derek Briggs, a paleontologist at the Yale Peabody Museum who has worked on fossils from this site for decades, says that the fossils would have had to form quickly to preserve the structures before they decayed. “The cuticle of the exoskeleton provides a kind of enclosed space,” Briggs says, "and the muscle tissue inside that decays but promotes the conditions that favor pyrite formation. The original cuticle decays in a matter of months, leaving the body and limbs preserved in pyrite.”

Xiaodong Wang

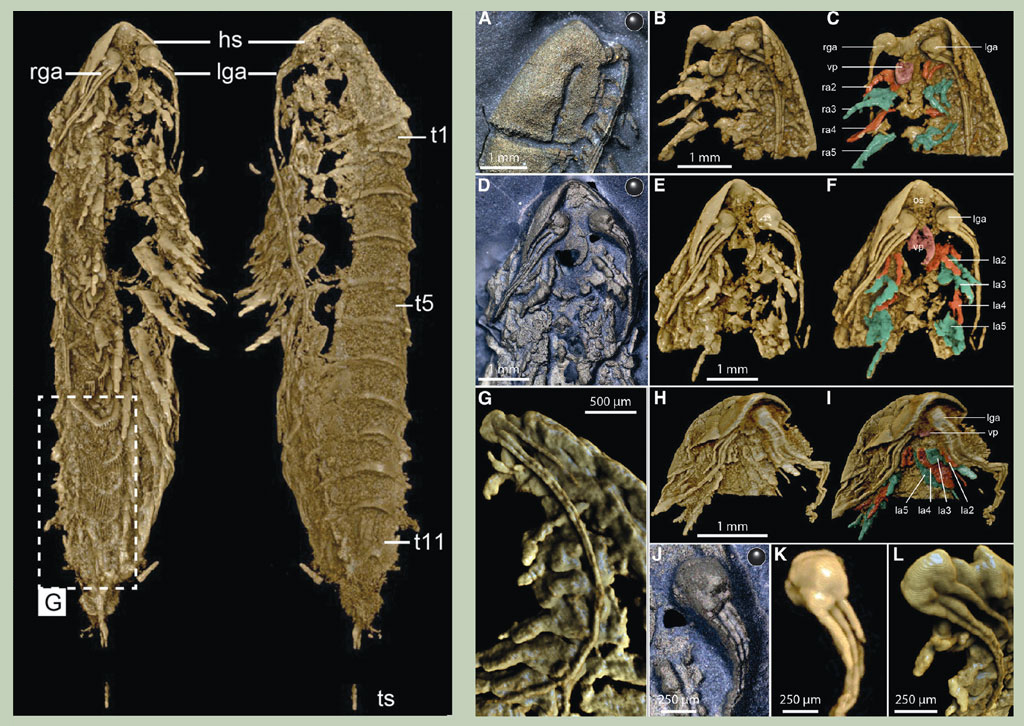

Pyrite is dense, which lends itself to imaging with computed tomography (CT) scanning. Briggs’s colleagues, Luke Parry of the University of Oxford and Yiu Lu of Yunnan University in China, conducted the imaging and modeling, as the team reported in a recent issue of the journal Current Biology. The fossils basically were imaged in digital slices that were combined by a computer into a detailed 3D model.

Luke Parry, Yu Liu, and Ruixin Ran. From Current Biology 34: P5578.

The vaguely shrimplike animal, which the team named Lomankus edgecombei, lived on the ocean floor during the Ordovician Period, about 450 million years ago. It belonged to a group of animals known as megacheirans, which thrived earlier during the Cambrian Period and were thought to be largely extinct by this time. Megacheirans had what’s called a great appendage, a modified pair of limbs on the front of their heads. In earlier megacheirans, this great appendage was equipped for capturing prey. But in Lomankus, it was reduced in size and sported long flagellae. That, along with its apparent lack of eyes, indicates adaptation for a dark, murky environment. The placement of its great appendage also reflects that of later arthropod antennae and mouthparts, providing some further suggestion of an equivalency between these structures. “These fossils tell us about the range of form and diversity in arthropods, and indirectly inform the evolution of the group as a whole,” Briggs said. “We knew very little about decay-prone arthropods from this part of the Ordovician, because we rarely get exceptional preservation from that age.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.