This Article From Issue

January-February 2002

Volume 90, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2002.13.0

Tree of Origin: What Primate Behavior Can Tell Us about Human Social Evolution. Frans B. M. de Waal (ed.) viii + 311 pp. Harvard University Press, 2001. $29.95.

We share about 99 percent of our genetic material with chimpanzees, but how far can we extrapolate from that? Does our genetic relatedness translate into observable behavioral similarities? In Tree of Origin, edited by Frans de Waal, primatologists explicitly address what it means for humans and apes to share such a small branch on the evolutionary tree.

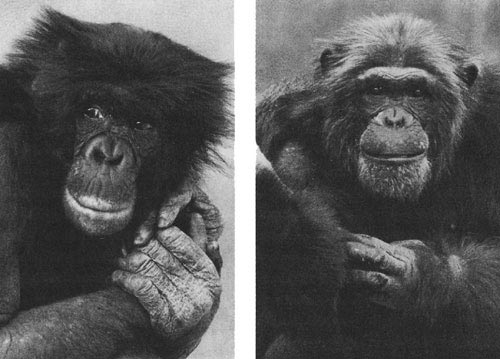

From Tree of Origin.

In nine engaging and provocative essays, five broad themes are covered: ecology, reproduction, social organization, social sophistication and cognition, and hominization (the process that turned apelike primates into humanlike ones). Anne E. Pusey discusses the link between genetic relatedness and social organization and suggests that the secondary sex characteristics of humans led to our peculiar (relative to apes) social structure. In an essay on bonobos, de Waal argues that they are as valid a model system for human social behavior as chimpanzees. Richard W. Byrne and Robin I. M. Dunbar each discuss their theories on the driving force behind the evolution of primate intelligence. Byrne argues that the planning of action chains, like the preparation of certain foods by gorillas, was a step toward humanlike intelligence, and Dunbar suggests that the size of social groups drives the evolutionary expansion of the primate brain. Craig B. Stanford describes the evidence that hunting and meat sharing by male chimpanzees is used to secure and maintain alliances, and sometimes to attract females. He suggests that hunting may have driven the evolution of social intelligence. Richard W. Wrangham speculates that three dietary adaptations led to the development of modern humans: eating roots, eating large mammals and cooking. William C. McGrew argues that tool-use data from different communities of chimpanzees suggest that this species has "culture"—that is, traditions within a community that get passed to subsequent generations. Charles T. Snowdon explains the link between animal communication and human language abilities. And Karen B. Strier suggests that broadening the range of primate species we study would give us a better idea of what is unique to the great apes, including humans.

A recurring theme is the remarkable flexibility of primates. Scientists are only now beginning to understand the degree to which primates can adapt to widely varying situations. A given primate individual comes into the world with a genetic inheritance that broadly defines its lifestyle, but the actual details depend on local habitat, demography and the individual's history.

Consider, for example, young monkeys, who normally scream only when they are being threatened or attacked; they do so to get help from their mothers. They have different scream types depending on the nature of the attack and the identity of the attacker. But Byrne and a colleague observed a young baboon who learned to scream in order to steal food from an adult baboon. He figured out that if he was near an adult baboon with food and his mother was out of sight, then he could scream and his mother would rush in and chase away the baboon—who would often drop the prized food. (Importantly, the young baboon only did this with baboons that were of lower rank than his mother.)

Also, McGrew describes how one community of chimpanzees adopted the use of stone "hammers" and "anvils" to crack open nuts, while just across the river, another community used other means to open nuts. Other examples of flexible behavior abound. To quote Dunbar, "primates are so supremely flexible in their behavior that it is almost meaningless to try to define the 'typical' anything for a species."

The contributors do an excellent job of describing and explaining the behavioral similarities and differences between humans and our closest relatives, but they fail to investigate what mechanisms underlie such behaviors. As the founders of modern anthropology—scientists such as Raymond Dart, Wilfred Le Gros Clark and Grafton Elliot Smith—understood, if the brain is the organ of behavior, then neurobiology should occupy a prominent role in primatology. Judging by the treatment of the primate brain in these essays, primatologists are in dire need of an up-to-date comparative look at the subject.

To be sure, the uniqueness of the primate brain is mentioned by most of the contributors, but only in reference to the size of the neocortex relative to body size or some other variable. In fact, the size of the neocortex figures prominently in Byrne's, Dunbar's and Stanford's theories of primate intelligence. The neocortex has expanded greatly in primates (and other social animals), but relating neocortex size to behaviors is controversial and provides little insight into behavioral differences between primate species.

The neocortex is not a homogeneous piece of neural tissue; it is modular in organization, and the number and relative size of different cortical areas can vary depending on the primate species. Even within a single cortical area there is diversity across primate species. In the primary visual cortex, for example, apes and humans differ from Old World monkeys in the arrangement of one subset of connections between the thalamus and the primary visual cortex, and humans differ from apes in another subset of these connections. As de Waal himself suggests, a more refined look at primate brains will give us much greater insights into the mechanisms underlying the diversity of primate behaviors.

Despite it cursory treatment of mechanisms, Tree of Origin is well worth reading for the diversity of opinion in these eloquent essays on the primate origins of human behavior.—Asif A. Ghazanfar, Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, Tübingen, Germany

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.