A Life with Whales

By Hallie Sessoms

A brief review of Into Great Silence: A Memoir of Discovery and Loss among Vanishing Orcas, by Eva Saulitis

A brief review of Into Great Silence: A Memoir of Discovery and Loss among Vanishing Orcas, by Eva Saulitis

DOI: 10.1511/2013.102.228

INTO GREAT SILENCE: A Memoir of Discovery and Loss among Vanishing Orcas. Eva Saulitis. xvi + 249 pp. Beacon Press, 2013. $26.95.

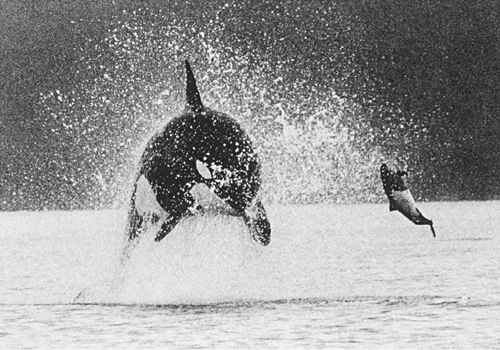

From Into Great Silence.

Naturalist and activist Susan Cerulean coined the phrase “origin moment” to describe points when our thinking is set on a new course. For Eva Saulitis, one such moment occurred at age 23 when, on break from a laborious job in a fish hatchery, she noticed a single orca in the tumultuous waters of Prince William Sound, Alaska. Into Great Silence , Saulitis’s memoir, documents the 25 years she has spent studying orcas in the wild.

Saulitis’s curiosity about the lone orca led her to get an M.S. in marine biology; she subsequently earned an M.F.A. in creative writing in order to better communicate what she was learning. Her life’s work centers on a small group of orcas known as Chugach transients, which she studies each summer with her partner, a biologist. In eloquent prose, she recounts her training as a scientist, transporting readers to the stunningly beautiful shore of Whale Camp in Prince William Sound. The book is composed of 48 short chapters, many just a few pages long. Saulitis does not skimp on scientific detail—or on vivid storytelling. In Chapter 25, “Mercifully Untranslatable,” she describes meeting a captive orca for the first time:

An orca’s irises are blue. It’s something you’d never know if you didn’t see one like I did that night, from five feet away. . . . I could count on one hand the number of times a wild orca had looked me in the eye. What does it see? What does it think and feel? I know what I feel. I feel my heart pinned in its gaze.

From Into Great Silence.

Elsewhere, Saulitis memorably describes huddling on the deck of the research vessel Lucky Star, straining to hear the orcas’ calls while wiping stinging rain from her face. As I read her telling of how the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989 reverberated through the community, my pulse quickened and my chest ached with fear not just for the orcas, who are introduced as unique individuals and whose numbers are dwindling, but for the future of the natural world.

The Chugach transients’ struggle to survive against mounting odds is told in parallel with Saulitis’s diagnosis with breast cancer. We learn in the introduction that she wrote the book while undergoing and recovering from chemotherapy in 2011. Although Into Great Silence is emphatically a story of the orcas, the context in which it was written makes the book a microcosm of the inextricably linked human and environmental health issues we face.

The book is a must read—at once a visceral reminder of the fragility of our ancient planet, a requiem for its rapidly diminishing nature and a call to arms.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.