A Mathematician Vanishes

By Daniel S. Silver

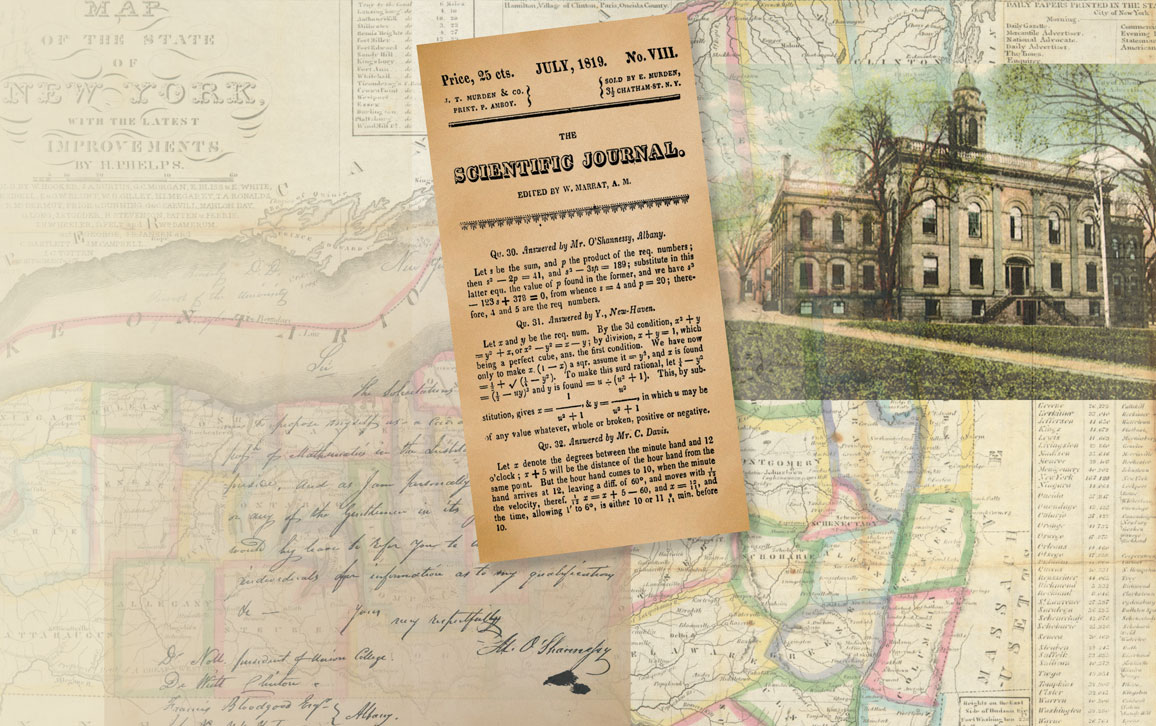

A sex scandal and anti-Irish sentiment doomed Michael O’Shannessy’s career, but two of his students left their mark on science.

A sex scandal and anti-Irish sentiment doomed Michael O’Shannessy’s career, but two of his students left their mark on science.

In 1826, a perplexing sex scandal engulfed the career of the rising Irish-American mathematician Michael O’Shannessy, a professor at the Albany Academy, a prestigious college-preparatory school in Albany, New York. There is much that we do not know about O’Shannessy and probably never will. We do know that the floodwaters that immersed the mathematician lifted the early careers of two figures who would be remembered: the scientist Joseph Henry and the engineer William H. Sidell.

Pictures Now/Alamy Stock Photo

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.