This Article From Issue

July-August 2007

Volume 95, Number 4

Page 362

DOI: 10.1511/2007.66.362

The Volterra Chronicles: The Life and Times of an Extraordinary Mathematician, 1860-1940. Judith R. Goodstein. xxvi + 310 pp. American Mathematical Society, 2007. $59.

The name Volterra is widely known today as half of the eponym Lotka-Volterra. The Lotka-Volterra equations describe the dynamics of predator-prey relations, explaining, for example, why populations of hares and lynxes tend to oscillate, never settling down to a stable equilibrium. The model is a keystone of modern ecology, but for Vito Volterra the development of those equations came as a late and almost casual digression in a long and varied career. Mathematicians may know certain other aspects of Volterra's work—and other eponyms, such as Volterra functionals and Volterra integro-differential equations. The life of the man behind these terms is not so well known, at least outside his native Italy. Judith R. Goodstein, the chief archivist of Caltech, now brings us the first full-length biography in English.

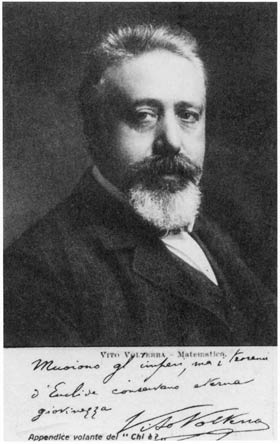

From The Volterra Chronicles.

Volterra's career followed a stately parabolic trajectory. He was born into a family of very limited means, and his prospects were further dimmed by the early death of his father. But with the grudging support of an uncle, he attended university, began publishing original work while still an undergraduate, earned a degree in physics and was appointed to a full professorship at the age of 23. He taught in Pisa, then in Turin, and in 1900 moved to Rome, where he took a prominent role not only in scientific and academic affairs but also in national politics. In 1905 he was named a Senator of the Kingdom of Italy, a lifetime appointment to the upper house of parliament. He was also elected president of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, the prestigious academy that traces its history back to Galileo.

All of those accomplishments constitute the upward arc of the parabola. Then came the regime of Benito Mussolini. Volterra was Jewish, and that fact alone would have been enough to ensure his eventual expulsion from the inner circle, but he hastened his ostracism by steadfast and outspoken antifascism. The final crisis came in 1931, when all professors in Italian universities were compelled to sign an oath of allegiance to the fascist government. Out of 1,250 professors, Volterra was one of only 12 who refused. His fate was not quite as grim as it might have been elsewhere in Europe—he died in his own bed, in 1940, at age 80—but he was stripped of all his academic positions and drummed out of the Lincei. In his last years he continued working, but mostly with colleagues abroad.

Goodstein gives a careful and detailed account of the events that led up to this extraordinary act of defiance and renunciation. Volterra was no radical firebrand; he might have been even more appalled if the leftist opposition to Mussolini had come to power. He was a lifelong royalist and nationalist. Although he opposed an Italian colonial adventure in Libya in 1911, just a few years later he campaigned ardently for Italian intervention in World War I, and he accepted a commission in the army at age 55. In the end, it remains a puzzle of human nature why Volterra stood firm against Mussolini while so many others (including all his closest friends) made their accommodation with the regime. Perhaps he saw more clearly than the rest what was coming. Or perhaps he just found the oath too much of an insult to the dignity of a professor and a senator.

Politics on a smaller scale—the intense bickering and negotiations of academic life—also get plenty of attention in Goodstein's account. Volterra did not glide effortlessly from one distinguished chair to the next. He had to fight or at least bargain for all of his appointments. In one case he was in the awkward predicament of competing against an older mathematician who had earlier been a mentor and benefactor.

Goodstein also offers an interesting portrait of family life. Volterra lived with his mother until he was 40, when she undertook to arrange his marriage to a second cousin in a much wealthier branch of the family. After the wedding, his mother moved in with the couple and remained a part of the household until her death in 1916.

The subtitle of this volume promises us "the life and times of an extraordinary mathematician," and the book delivers fully on the life-and-times part of the promise. Unfortunately, we learn less about what made the mathematician extraordinary, and at times this gives Volterra's figure a certain disturbing hollowness. As he climbs the academic ranks and delivers lectures in Paris and Berlin, we have to take it on faith that his work merits this recognition, because most of the mathematics goes unexplained. On a few occasions, Goodstein does undertake to present mathematical ideas, and she does a splendid job of it. For example, there's a two-page discourse on the concept of a functional, which puts Volterra's ideas in their historical context and offers at least a glimmer of understanding: Whereas an ordinary function relates one number to another number, a functional relates one function to another function. More passages of this kind would have been welcome. (An appendix reprints an essay by Sir Edmund Whittaker from the Obituary Notices of the Royal Society of London, which gives a good account of Volterra's mathematical work, although it is perhaps too technical for many readers who would be attracted to this book. Other appendices give English translations of two talks by Volterra.)

Allow me a final comment on the Lotka-Volterra equations. Volterra's interest in population dynamics was inspired by the work of his son-in-law, Umberto D'Ancona, a marine biologist who observed unusual fluctuations in species abundance when commercial fisheries were interrupted by World War I. Volterra was in his sixties at the time. What about Lotka? Alfred J. Lotka was not Volterra's colleague or collaborator; as far as I know, the two men never met. Lotka discovered the same model about a year earlier than Volterra. Lotka is also an interesting figure, whose life trajectory was not a parabola but something like a random walk. At various times he worked as a chemist, a patent examiner, an editor of Scientific American and a statistician at the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Perhaps someone will see fit to tell his story as well.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.