This Article From Issue

September-October 2006

Volume 94, Number 5

Page 472

DOI: 10.1511/2006.61.472

Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors. Nicholas Wade. vi + 312 pp. Penguin Press, 2006. $24.95.

A few weeks ago, I mailed in a cheek swab with a bit of my DNA to a forensic genetics laboratory. A CD and printout came back showing me the genetic contribution made to me by my ancestors for the last few thousand years on both my mother's and my father's sides. Being able to obtain this sort of information is one more thing that in the 21st century we have come to take for granted, like seeing the latest NASA photos of Mars online or phoning home while on a cruise to Antarctica. Companies have popped up that offer to analyze your DNA and, using genetic markers that are unique to certain ethnic groups, tell you the mysteries of your history. Many people who thought they knew their family's history, who even had a family Bible with generations of written records of parentage, have been shocked to learn that despite having been raised to believe they were white Americans, they are actually substantially African-American or Native American, or vice versa. In my own case, I learned that I have a good amount of Native American ancestry, of which I had had no inkling. This is human history in action, its effects as up close and personal as possible.

In Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors, Nicholas Wade, a science writer for the New York Times, has woven a detective story from three strands: the human fossil record, archaeological findings and our increasingly detailed understanding of humankind's genetic history. Researchers are uncovering a record of ancestry and ethnicity stretching from you and me all the way back to the people of the Neolithic, with some startling results.

Before the Dawn is a popularized look at the latest efforts to understand the entire human past, with an emphasis on the past 5,000 to 10,000 years. Thus this volume complements other recent books that cover in greater detail the more ancient past—our emergence from the ape lineage that produced us.

From Before the Dawn.

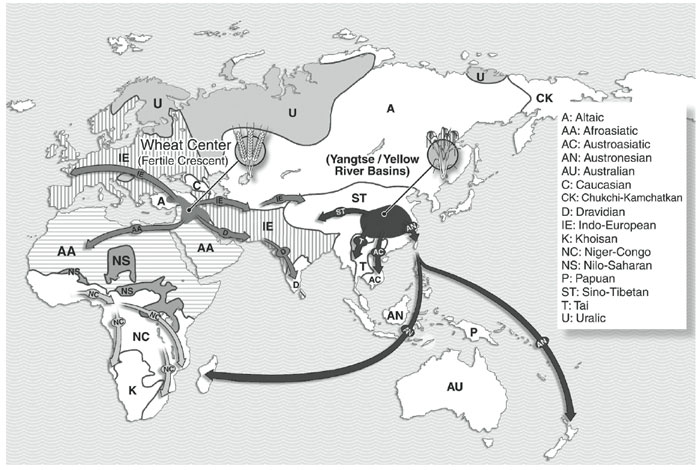

After routinely covering the very early steps of human history—the discussion is largely limited to the evolution of the human form—Wade dives into the great human dispersal of early Homo sapiens across the planet. Scientists can trace this diaspora using a variety of methods. Geneticists make use of mitochondrial DNA. Unlike the better-known variety of DNA in the nuclei of your cells, the DNA in mitochondria undergoes mutations at such a high rate that small differences among recently divided populations can be studied. Because mitochondrial DNA passes only through the maternal line, we can trace direct maternal ancestors back thousands of generations. Results from mitochondrial studies first provided evidence in the 1980s that the genetic differences among all modern humans are trifling. This finding was bolstered more recently by studies of the evolution of the Y-chromosome. These investigations have provided the male side of human history and have largely corroborated the early mitochondrial findings. Studies using these methods have shown, for instance, that Africans in Uganda who have long claimed to be the children of an ancient Hebrew priest actually are so, and that Thomas Jefferson's many living descendants include some whose maternal line goes back to his slave and mistress Sally Hemmings. And thousands of people, including me, have been able to learn who our ancestors really were.

Wade deftly follows the genetic detective story across all the continents and some 50,000 years of our history, explaining recent findings about the peopling of Europe and, much later, the Americas. He shows that the concept of a single diaspora is simplistic. People have been migrating in repeated waves down through the millennia, and Europe and every other populated continent has seen multiple invasions and immigrations, the records for which are preserved in every cell in our bodies.

Wade also addresses cultural factors in evolution. He spends two chapters describing the work of historical linguists, who have tried to corroborate the genetic record of population movements, with some success.

If there is a flaw in this tightly written, insightful book, it is that Wade provides perhaps too many of the stock examples of human evolution. In my view, he spends too much time and space attempting to convince the reader that we did indeed evolve from apes (duh!) and that our own social behavior and cognition have roots in the deep human past. I say this only because I think readers would have preferred to hear more about the discovery of such evolutionary mile-markers as the wearing of clothes, the invention of agriculture, the peopling of the Earth and so on. These are the whys and wherefores of our existence. Before the Dawn provides ample evidence that scientists are hard at work answering these and many other questions about a subject that has long been the stuff of myth and mystery.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.