Thoreau as Naturalist: A Conversation with Four Authors

By Dianne Timblin

To mark the bicentennial of Henry David Thoreau's birth, four authors discuss his important—but largely overlooked—work as a naturalist.

To mark the bicentennial of Henry David Thoreau's birth, four authors discuss his important—but largely overlooked—work as a naturalist.

To mark the bicentennial of Henry David Thoreau's birth, we spoke with four authors who have spent countless hours studying his work as a naturalist. Richard Higgins is the author of Thoreau and the Language of Trees, which draws on 100 excerpts from Thoreau’s writings to explore and discuss his knowledge of and connection to trees. Conservation biologist Richard B. Primack’s Walden Warming: Climate Change Comes to Thoreau’s Woods has become a touchstone for ecologists, climate scientists, and environmental historians. Geologist Robert M. Thorson’s latest book on Thoreau, The Boatman, examines the Concord River’s vital influence on Thoreau, with a particular emphasis on how the encroachment of industrialization spurred an evolution in his thinking. Laura Dassow Walls has spent decades excavating details of Thoreau’s life from libraries and archives; she offers them to readers, alongside her formidable analysis and insight, in her forthcoming biography, Henry David Thoreau: A Life, available in July. The conversation that follows is a somewhat expanded version of the one that appears in our Aug–Sep 2017 print issue.

Although each of you has written about Thoreau’s work as a naturalist, you’ve all approached the topic from different perspectives. I’m interested in hearing what you each set out to do in writing about Thoreau. Let’s start with you, Dr. Primack. The environmental data Thoreau recorded has been vital to your ecological studies of the Concord, Massachusetts, area—something you discuss in your book Walden Warming.

Richard B. Primack: I wanted to demonstrate how Thoreau’s observations from the 1850s, when linked to modern observations, provide powerful evidence for the effects of climate change on plants and animals. For eight years Thoreau kept such detailed daily observations that we were able to clearly demonstrate the shift: Plants are now flowering and leafing out about two weeks earlier than they were 160 years ago.

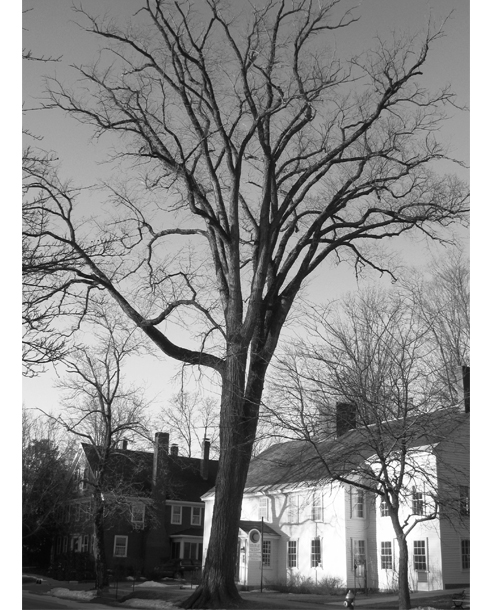

Above photo and photo at top of page by Richard Primack.

We could also discern that rising spring temperatures were driving these changes in timing; it was not another factor, such as changes in rainfall or land use. Thoreau’s observations also helped us determine that birds are not responding as dynamically to warming temperatures; that is, their arrival dates each spring are not changing much. In Walden Warming, I explore the implications of these changes, especially the possibility of seasonal ecological mismatches between plants and birds, as well as the insects that birds eat.

I also wanted to convey that many of Thoreau’s key themes in Walden—such as the value of living simply, the importance of carefully observing nature, and the moral reasons for taking political stands—are still very relevant. Among other things, they provide guidance to help us address the current crisis of global climate change.

Dr. Walls, when you approached your biography of Thoreau, you’d already written about him extensively. What were you aiming to do that you hadn’t had a chance to do before?

Laura Dassow Walls: My earlier book on Thoreau was specifically about Thoreau and science, and in writing it I had to break out material for a second book, on Emerson and science. As a result, I’m known for doing primarily “______ and science” studies. But I have never seen science as a separate zone, distant from literature, culture, religion, social reform, and so on—I approach science as a humanist. In all my books I have tried to show how the figures I’ve been centrally interested in (Thoreau, Emerson, Humboldt) integrated natural science into the fullness of human life and thought.

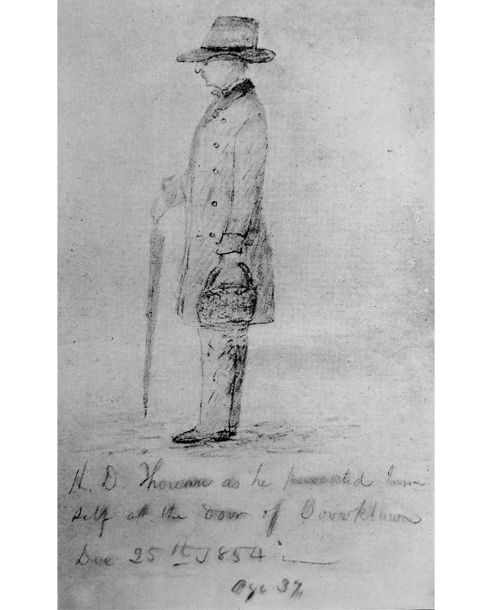

Photo from Henry David Thoreau, courtesy of University of Chicago Press.

Unfortunately, aside from the field of ecocriticism, most mainstream literary scholars persist in treating science as basically extraterrestrial and, at best, of marginal interest to them. Very little of my larger argument has really made an impact in literary studies. So one goal in writing my biography of Thoreau was to weave his work in science as fully as possible into the fullness of his life—including his life as a literary artist and as a social reformer—to show how inseparable these modes of thinking and living are, rather than to hive science off as if it could be a separate realm. It’s never separate—implicit assumptions about, say, the human relationship with nature, or to the Cosmos, as Humboldt would say—are always present in every literary work. My studies perennially focus on authors who make those assumptions explicit.

I also had another, very specific aim. I open the biography with the melting of the glaciers to make a point: Thoreau is deeply place-based, and one cannot understand him without understanding how his place came to be. What’s more, that’s what he thought, too; he was driven to understand how his world came to be. So viewing him through the lens of his region’s geological and natural history offers a chance to deepen our understanding of how he actually understood himself.

Yes, understanding Thoreau in the context of his regional environment seems essential. Mr. Higgins, your book Thoreau and the Language of Trees demonstrates that point by delving deeply into his observations of and enthusiasm for trees.

Richard Higgins: I wanted to convey chiefly the depth and power of Thoreau’s personal and creative vision of trees, which has been too little recognized. His engagement with and writing about trees was so sprawling and multi-faceted, however, that it posed a challenge: how to write a book about it that was not just a compendium or catalog, like a quotes book. His pioneering work in forest dynamics has also been written about—for example, in David Foster’s Thoreau Country—so I wanted to contribute something new. To keep the book focused on his personal response, rather than to analyze his views of trees, I decided to organize the book around five aspects of Thoreau as a human being: his eye, his heart, his mind, his poetic muse, and his soul. My intent was to enable people to, at least in some way, experience trees as he experienced them and seem them as he saw them. Doing so had a profound effect on me personally, and I hoped that it might for my readers as well.

Focusing on his personal response brings to the foreground the wonder, awe, and even reverence that trees stirred in Thoreau. He often had such feelings when he studied them as massive plants of enormous complexity, beheld them as natural objects of unusual beauty and form, or perceived them as symbols of spiritual truths. He sometimes had all three responses at once. I chose to concentrate on how trees influenced him as a poet and writer, a philosopher, and a spiritual supplicant because those responses, although based on his keen observations as a naturalist, have received less ink than his work in forest dynamics.

Photo from Thoreau and the Language of Trees, courtesy of Richard Higgins.

I also wanted to use Thoreau’s words and my images to show how he saw trees. I therefore tried to be as direct and original in my essays as possible, leaving the literary and scientific scholarship that informed my book to the notes. In addition, I wanted to show his unique, unpredictable responses to specific trees, because I found that the key to Thoreau’s grasp of the universal was in his attention to particulars. So the book includes chapters about Thoreau’s love of the white pine, the felling of an iconic Concord elm, his discovery of a forest of old-growth oaks, his joy at seeing trees transformed by snow, and his startling nautical imagery of trees.

And Dr. Thorson, your latest book, The Boatman, examines the influence of the Concord River on Thoreau.

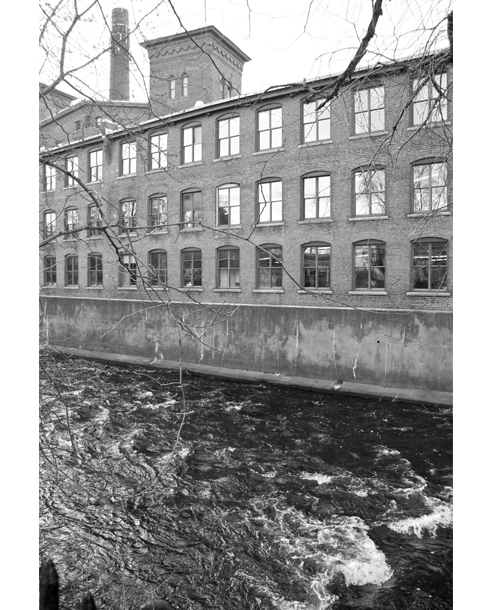

Robert M. Thorson: This project began 14 years ago with a question put to me by Leslie Perrin Wilson, curator of special collections at the Concord Free Public Library in Thoreau’s hometown of Concord, Massachusetts. After showing me an anonymous, rolled-up map more than seven feet long, she asked, “What do you make of this?” For the next 12 years, her question simmered in the back of my mind while I worked on other things. Only after finishing my 2014 book, Walden’s Shore, about the physical science beneath Thoreau’s literary masterpiece, and even then only after plunging deep into scholarly detective work on Thoreau’s river years, was I able to answer Leslie’s question. Her mystery map became my Rosetta Stone for Thoreau’s unpublished river project of 1859–1860, which he worked on secretly during America’s first major controversy over dam removal, a four-year legal fight that consumed four acts of the state legislature. In turn, this scroll-map, with its details of channel morphology, hundreds of soundings, seven distinct reaches, and 44 surveyed gradients, culminated Thoreau’s lifelong investigation into the ways and means of the Concord River, the largest feature of his home terrain—and, I would argue, the most vital influence on him.

“The quantitative details of Thoreau’s river project were excised from his journals when they were published in 1906, leaving his genius as a river scientist invisible.”

Keeping the mysterious map front and center, I aimed to squeeze the juice out of five other original source documents to reconstruct Thoreau’s life as a boatman and pioneering river scientist. These included an 1862 engineering report, with more than 35,000 data points; an 1860 report by a special legislative committee; the unpublished online transcripts of Thoreau’s journal; his massive unpublished table, Statistics of Bridges; and his private papers. Significantly, the quantitative details of Thoreau’s river project were excised from his journal writings when they were published in 1906, leaving his genius as a river scientist invisible during his 20th-century canonization. Ultimately, The Boatman endeavors to bring Thoreau’s riverine joy back into the limelight.

As you mentioned earlier, Dr. Walls, literary scholarship tends to pigeonhole Thoreau, leaving his scientific work largely undiscussed in that field. Over the years you’ve pioneered a more three-dimensional view of Thoreau by exploring his work as a naturalist, demonstrating how profoundly it affected his philosophy and writings. In your view, what does it mean for Thoreau to be understood as a fundamentally interdisciplinary figure?

LDW: To understand Thoreau as a fundamentally interdisciplinary figure is to perceive how science and technology, the social sciences, the humanities, and the arts all flourish together, not just in the abstract but in specific problems and studies. If we could truly understand how he put the picture together and made it meaningful, as well as factual, and profoundly moving in its beauty and splendor, we could ask how we might, in our own emerging world, educate ourselves to see the world whole and make disciplines into nodes of interchange instead of silos of exclusion.

I actually started thinking about Thoreau when I was studying to become an ecologist. His journals in particular absolutely fascinated me. They showed how one could be fully alive to the world in all its dimensions, and how living fully in the natural world—walking, noticing, forever asking questions—could be a way to live more fully, period. Thoreau’s later works are especially electric with creative energy, and the more he dug into the questions that engaged him, the better his writing became—the more embodied, the more distinctively “Thoreau.” Jacob Bronowski once wrote that creativity is making a deep connection between two things, a connection no one has made before. Thoreau went out every day looking for those deep connections. This became the project of his life—as a writer, making connections between language and the natural world, for starters, including “the language that all things speak,” as he said. But the natural world was very, very big for him—it included people, for instance, whom he studied with great care, both through literature and philosophy but, to be sure, through participant observation. He can seem to lack empathy for his fellow humans (why that is takes us far from this question!), but he shows immense empathy for everything wild—foxes, woodchucks, hawks, chickadees, also pine trees and apple trees—his empathy for grasses is simply stunning.

This means that he isn’t a scientist in the sense of being “objective,” because he assumes that human feeling, our emotional register, is part of human cognition—and indeed, as Humboldt said, just as much part of what he called the Cosmos as physical phenomena. Thoreau’s response to his world is always to inquire about relationships—as he put it once, his “point of interest is somewhere between” the object and himself, and he critiques scientists for ignoring the “between” and dealing solely with the objects. So Thoreau asks constantly about relationships between things—between the turtle egg and the temperature of the earth in which it hatches; between the bird and the plant materials it chooses to construct its nests—on and on, thousands upon thousands of questions.

Image from Henry David Thoreau, courtesy of University of Chicago Press.

The acute aliveness of his curiosity is what makes the greatness of his writing—there is simply no separation in his mind, no compartments for all the various kinds of knowledge he seeks. He brings all his senses to bear. For example, he notices a certain plant is cool to the touch, but the dead leaves of the same plant are warm to the touch. It’s not just that he notices, as a “fact,” but that he makes something of it—and of all the thousands of observations like this—because he wants to know why—he’s the perpetual child, perpetually fresh with wonder. And this desire to know why leads to the other aspect of his curiosity—he wants to know how things work, which to him is part of appreciating their beauty. Machines fascinated Thoreau, and he was an accomplished inventor (his graphite mill made the Thoreau family fortune); what’s more, he insisted that any well-educated person should know, for instance, how a railroad engine runs, well enough to repair it if necessary. In his mind, to go from asking how an engine works, to asking how a forest works, or how a river works—or how a democracy works!—was not a leap at all. And the more he knew, the bigger the universe got and the more interesting; he couldn’t resist sharing his knowledge, and sharing it in such a way that the reader or student might find it irresistible.

Asking how things worked, and what they meant, took him in all directions—into all “disciplines,” we’d say today. He wanted to understand the workings of politics and society as well; when asked, by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, to indicate his field of interest, his answer (“the Manners and Customs of the Indians of the Algonquin Group previous to contact with the civilized man”) would today make him an anthropologist. And he began every study by researching its history. He didn’t regard Native Americans as ignorant because they were pre-scientific, but as knowledgeable in a different way; he didn’t regard the earliest naturalists as “obsolete” merely because they were old. For instance, during his year of exploring Darwin, one of the most intensely creative periods of his life, he went back and reread 16th-century herbalists, putting Darwin in relation to his predecessors. And finally, Thoreau was above all else a literary artist: He’d started life determined to be a poet, and he kept and honed lifelong his acute sensitivity to language. That makes him not only a great writer, but a great writer on science. It’s painful to recall how young he was when he died, so soon after Darwin lit up his world; had he lived another 20 years, we would have a better sense of how he was drawing multiple disciplines into a varied but coherent body of work.

I’m very curious about what this shift in perspective might signify for those in the sciences. What does science gain by, in effect, claiming Thoreau? Or what might those working in STEM—regardless of their field—gain through greater awareness of his work?

RH: In a practical sense, you might say this question has been answered by Richard [Primack] and other scientists who have used Thoreau’s extensive phenological records to study how climate change has affected when plants flower and leaf out or when bird and insect migrations occur.

Scholars have for 25 or more years been diving into the wealth of botanic observations, charts and tables, and other data Thoreau recorded for his grand phenological calendar of Concord but did not live long enough to synthesize. Because these records had been omitted from posthumous publications, it took some time for the data to come to light. The field of forestry also ignored Thoreau’s published findings about succession and dendrochronology, but for a different reason. They didn’t trust the observations of a Transcendentalist.

Although reclaiming these facts has been important, it’s even more crucial for scientists to cultivate Thoreau’s idea that the factual is only partial. As he sought to understand nature, he came to believe that a strictly quantitative or “microscopic” perspective was too narrow, too circumscribed, to deliver the whole—or even, as he wrote, “the shadow of the whole.” Thoreau valued science, but he always combined his exacting observations as a naturalist with his aesthetic and philosophical perception. He wanted to know the tree as natural fact and as spiritual fact. Not a bad way to look at the world.

RMT: Most importantly, Thoreau gives us a model for how the information-making goal of science and the meaning-making goal of the humanities can happily coexist in equal doses in one mind. Of course, this was before these two endeavors were rifted apart in the second half of the 19th century during the professionalization of science. It’s helpful to remember that Thoreau’s era predated use of the word scientist as a cultural meme, a label invented as a counterpart to artist.

Photo from The Boatman, courtesy of Robert M. Thorson.

Secondly, scientists can go back in time to witness the great joy Thoreau experienced while satisfying his intellectual addiction to unfunded, curiosity-driven research. For example, on a beautiful autumn day in 1851 he exclaimed, “What meandering! The Serpentine, our river should be called? What makes the river love to delay here? Here come to study the law of meandering.” Combining field observations and inductive genius, he discovered that law of helicoidal flow the following spring. This is not the Thoreau we’ve been steered toward by those preoccupied with his literary, philosophical, and political achievements.

A third reason for claiming Thoreau as a scientist involves the wonderful historical data sets he left for us to work with: most notably the phenology of plants, animals, and physical occurrences. My most recent book is accompanied by an online repository of data that Thoreau collected and mapped that provides a historical baseline for changes that have occurred since. Quantitative examples include the width, depth, shape, curvature, velocity, discharge, migration rate, and temperatures of flowing streams throughout the watershed during both flood stage and baseline flows.

RBP: Thoreau shows us that it is possible to understand the natural world through careful observations—ones made during intensive hours on single days, and made daily over the course of many years. Thoreau’s observations provide us with a model for conducting climate change research that’s applicable to both professional scientists and the expanding network of citizen scientists. He gathered scientific data primarily by writing down his observations in a systematic manner; his most advanced instrument was a thermometer. The tens of thousands of citizen scientists who are currently contributing to online networks—such as the National Phenology Network, Project Budburst, Journey North, and eBird—are all linked to this tradition of careful observation. If scientists can use Thoreau’s practices and insights to demonstrate the power of naturalist observations, this could inspire more people to observe their own surroundings, join the ranks of citizen scientists, and become involved in protecting the environment.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.