This Article From Issue

May-June 1998

Volume 86, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/1998.25.0

Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes: New Translations & Interpretations of the Primary Texts. Martin J. S. Rudwick. 301 pp. University of Chicago Press, 1997. $34.95.

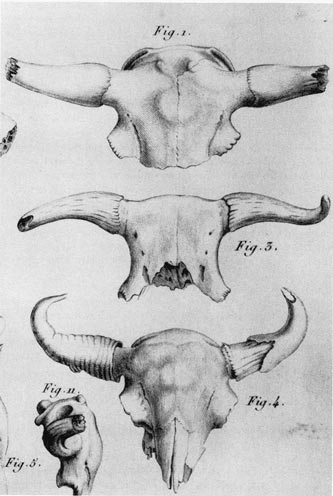

From Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophies.

The book's jacket claims that until recently Cuvier was seen as an arch-conservative, remembered only for his opposition to evolutionism and his support for geological catastrophes and the reality of Noah's flood. No disrespect is intended the author to suggest that these claims are a little exaggerated. The book is dedicated to the late William Coleman, whose 1964 biography undermined many of the traditional myths about Cuvier, and Martin Rudwick's own 1972 The Meaning of Fossils continued the trend. Anyone who has kept in touch with the history of science over the past few decades knows that Cuvier played a major role in vertebrate paleontology's origin, creating a science of the earth's past that—although certainly catastrophic—was designed to replace rather than defend the Biblical viewpoint. Myths die hard, however, and it is no bad thing to have the reinterpretation of Cuvier's position backed up by more intensive study and wider publicity. Rudwick believes that his subject has still not received the attention he deserves and is engaged in a major project to reconstruct Cuvier's legacy. As a prelude to what will eventually be a substantial reinterpretation, this volume offers a selection from Cuvier's writings, all newly translated, with Rudwick's commentaries on the significance of each piece.

From Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophies.

The key to the new vision of the earth's history was the reconstruction of extinct species from their fossil bones. To this end Cuvier employed his immense skills as a comparative anatomist (which also induced him to revise substantially the methodology of biological classification and the divisions of the animal kingdom). Cuvier could show that the earth had once been populated by a vast number of species unlike those still alive today. Some, like the mammoth, were related to modern forms but distinct, whereas others were unlike any living species. Equally important was Cuvier's stratigraphy: With Alexandre Brongniart, he recognized the sequence of stratified rock depositions in the Paris basin and noted that different populations replaced each other through time, leading step by step to the present. The transitions' suddenness from one stratum to the next, hence from one population to the next, convinced him that the species of each period were wiped out by geological catastrophes. But he made no effort to link the last catastrophe with Noah's flood, and indeed went out of his way to argue that it was not worldwide, as the Bible implied.

Rudwick translates several Cuvier papers on extinct species and discussions on the theory of the earth. Some smaller pieces from letters are not easily accessible, and even some of the better-known texts have been supplemented with additional material from Paris manuscripts. The two most important texts are Cuvier and Brongniart's 1808 "Essay on the Mineral Geography of the Environs of Paris" and, from 1812, Cuvier's "Revolutions of the Globe," published first as an introduction to his collected papers on fossil bones. The latter is the founding document of Cuvierian catastrophism, but a new translation here is particularly important because—as Rudwick explains—the original English translation by Robert Jameson not only distorted Cuvier's text but also included notes designed to give the impression that Cuvier himself wanted to link his theory to the Biblical view of the earth. By freeing Cuvier from Jameson's straightjacket, Rudwick for the first time allows him to speak directly to the English-language audience.

This edition of Cuvier's writings will become an essential tool for all who research and teach the history of geology, paleontology and evolutionism. It will also, I hope, lay to rest at last the myth of Cuvier as a purely negative thinker and pave the way for Rudwick's more extensive study.—Peter J. Bowler, History and Philosophy of Science, The Queen's University of Belfast

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.