This Article From Issue

May-June 2024

Volume 112, Number 3

Page 184

ALIEN EARTHS: The New Science of Planet Hunting in the Cosmos. Lisa Kaltenegger. 288 pp. St. Martin’s Press, 2024. $30.00.

We stand at the doorstep of a scientific revolution: The discovery of extraterrestrial worlds that resemble our own could be just around the corner. For more than a decade, we have known that planets that are roughly the mass and radius of Earth orbit other stars. Without more detailed observations, however, these worlds are merely Earth-sized cue balls. Until now, astronomers have not possessed the capability to characterize exoplanets the size of Earth. But with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in 2021, everything changed. The hunt is on.

Carsten Steger/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

It’s fitting, then, that Alien Earths, Lisa Kaltenegger’s new book on the science of planet hunting in the cosmos, opens with a scene of her watching the launch of JWST. Like her, I was glued to the NASA TV livestream on my laptop that Christmas morning. Ten billion dollars of scientific equipment and an untold number of PhD theses were riding on a rocket that “carried the dreams,” Kaltenegger writes, “of thousands of scientists like me, hoping to catch a glimpse of the cosmos that had been beyond our reach—and our view—until now.”

Alien Earths is, fundamentally, a book about hope. There’s no guarantee that astronomers will discover signs of life beyond Earth anytime soon, even with the fantastic capabilities of JWST. But thanks to researchers like Kaltenegger, humanity is closer than ever before to answering the age-old question: Are we alone in the universe? Kaltenegger’s career—from her formative undergraduate years in Austria through her current position as the director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University—has been dedicated to putting humanity in the best possible position to identify signs of alien life.

Kaltenegger is an astrobiologist: She studies life’s origins, distribution, and fate on Earth and in the larger universe. There is a double challenge in astrobiology: First, we must develop the capacity to detect the subtle imprints of alien biology; second, we must expand our understanding of life’s possibilities so we can recognize that a puzzling measurement indicates life rather than some bizarre geological process. Not one to recoil from a dare, Kaltenegger works on both sides: modeling different types of planets so we know where and how to look, and studying different types of life so we know what to look for. Throughout her book, Kaltenegger takes us on trips into her lab, where she grows microbes of every color in the rainbow to learn how to detect their chemical fingerprints with a telescope, and also into her computer terminal, where she whips up worlds populated by different combinations of life-forms via strings of code.

Alien Earths explores not only what Kaltenegger does as a scientist, but also why. The anecdotes that Kaltenegger shares give readers a glimpse into what has informed her research interests and approach to her work. We get a sense of what her dreams are—the passion for her work that led her to cross oceans in pursuit of her career, seek out colleagues from a range of other fields, and establish the Carl Sagan Institute. She also recounts her personal journey in academia. Kaltenegger does not shy away from describing the challenges she’s faced throughout her career as an alien hunter—“They kept asking why I was working on something I might never find”—and as a woman in astronomy, a traditionally male-dominated discipline.

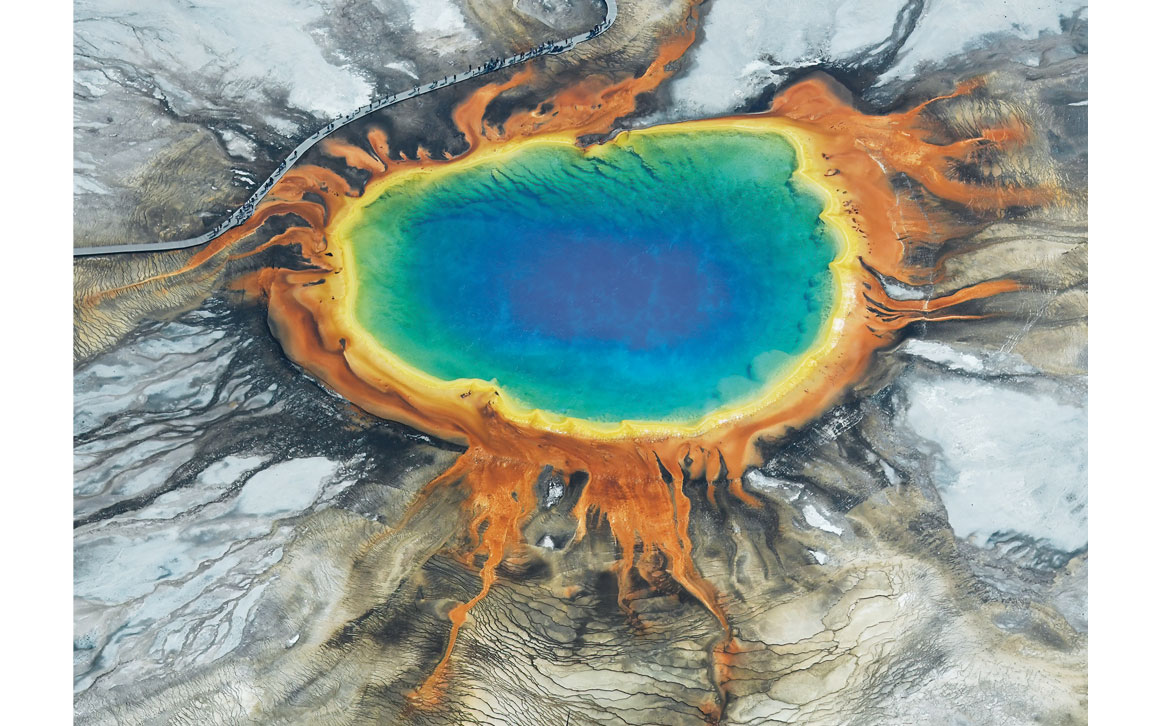

In one memorable passage, Kaltenegger describes how, as a postdoc in 2008, she discovered her scientific niche while on a trip to Yellowstone National Park. Mesmerized by the biological hues of the Yellowstone hot springs, Kaltenegger realized her calling:

Watching these colorful organisms made me notice how broad the range of colors of life are. Just imagine a planet with hot sulfur springs covering its surface, where life creates a rainbow-colored world. I realized that astronomers needed a color catalog of life—a database of diverse Earth biota and information on how they reflected incoming starlight—to compare to what our telescope would find on exoplanets. If we didn’t want to miss out on finding life in the universe, scientists needed a comparison chart that included more than just green plants.

While observing a geological wonder, Kaltenegger had identified a missing piece of the astrobiological puzzle: a chromatic archive of life’s diverse pigments against which to compare astronomical observations. In other words, looking for life requires knowing about the different ways that life can look. This realization sparked her to fill that gap through an innovative blend of biology and astronomy: by growing microbial life in the lab and simulating how such life on an alien world might appear through a telescope.

Beyond Kaltenegger’s personal contributions to the field, Alien Earths is also an expansive introduction to the multidisciplinary field of astrobiology. Though you’ll find deeper explanations of certain scientific topics in other, more focused texts, Kaltenegger successfully connects ideas from disparate fields—from prebiotic chemistry to geology to astronomy—to reveal a big-picture understanding of the possibilities for life in the universe. Her lyrical prose weaves the wonder of discovery, the thrill of cutting-edge research, and the splendor of the cosmos into an accessible and inspiring read. Particularly impressive are her clever analogies that make the impossibly large (in size) or long (in time) more reader friendly. For example, Kaltenegger translates how fast our Sun is losing mass (five million tons per second) into a more visual unit: 50,000 adult blue whales per second. In another instance, explaining how the ocean tides created by the gravity of both the Moon and the Sun are slowing Earth’s rotation by roughly two milliseconds each century, she quips: “That means that in about two hundred million years, I will finally get that extra hour of the day I’ve always hoped for.” Who among us can’t relate to that yearning for an additional hour of time?

The book packages a vast array of research into an elegantly written, logically laid-out story. The first half of Alien Earths surveys the principles of planetary habitability, theories about life’s origins, and techniques that scientists use to look for life beyond Earth. In the second half, Kaltenegger plays exoplanet tour guide, showing off the amazing worlds that astronomers have found orbiting other stars—big and small, near and far, scorching hot and just the right temperature (perhaps) for life. Here, we get a sense of how exoplanetary science is swirling toward the detection of possibly habitable worlds.

In other words, looking for life requires knowing about the different ways that life can look.

Kaltenegger leads with the discoveries of hot Jupiters, the first kind of exoplanets to be found orbiting Sun-like stars. Although these gargantuan puffballs are far too toasty to sustain life as we know it, they nonetheless demanded significant revision to our conception of planet formation. She then describes how NASA’s Kepler space telescope, launched in 2009, brought us down in scale to super-Earths, between the size of Earth and Neptune; the detection of such worlds revolutionized our understanding of planetary diversity, because our solar system lacks anything comparable.

Though we owe thousands of exoplanet discoveries to Kepler, this spacecraft failed to find true Earth analogs that could be readily interrogated for chemical signs of life. Motivated to discover the nearby exoplanets that would be most amenable to searching for alien biospheres, Kaltenegger played a leading role in making NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission possible. When the time finally came for the launch of TESS in 2017, she brought her family to Cape Canaveral to witness the event. She was not only able to share the wonder of that rocket launch with her four-year-old daughter, but also the wonder of thousands of additional exoplanet discoveries with like-minded individuals.

Alien Earths conveys how difficult the search for life in the universe is—and the incredible advances that have finally put scientists in a position to try to answer that age-old question. Although Kaltenegger never quite gives an answer to what that life might look like (the universe is bound to surprise us), she provides an extraordinary tour of how science has developed the tools that will bring us closer to finding and recognizing alien life. In other words, it’s more about the journey than the destination.

With the launch of spaceborne observatories like Kepler, TESS, and JWST, we are living through an exoplanetary revolution: one led, in no small part, by Kaltenegger herself. Throughout the book, she maintains a sense of optimism, writing, “Among the thousands of exoplanets we have discovered, perhaps we have already found the first that could be an alien Earth. With two hundred billion stars in our galaxy alone, the odds of finding life seem to be ever in our favor.”

Alien Earths reminds us that although there have been many triumphs in exoplanetary science to date, the biggest discovery of all still lies in wait.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.