An "Invisible Gorilla" in the Lab

By Kristen Koopman

Selective inattention to women’s experiences in STEM leads to a chilly workplace climate for women, who pick up on even the subtlest cues.

October 2, 2018

Macroscope Sociology Social Science

Earlier this year, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine released a report on sexual harassment in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics professions (STEM). The report does an excellent job of laying out the landscape of work on STEM and gender, particularly when it comes to one of the more nebulous, yet pervasive, aspects of sexual harassment: gender harassment.

Illustration by Barbara Aulicino

The National Academies defines gender harassment as “verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey hostility to, objectification of, exclusion of, or second-class status about members of one gender.” One important thing to note is that these behaviors don't have to be intentional, and as the report shows, they can even be institutional rather than individual. Indeed, there has been a lot of work done on unintentional gender-based exclusion in STEM that deserves attention.

In 2009, a study group led by Sapna Cheryan of University of Washington used the concept of “ambient belonging” to show that the presence of stereotypically male-gendered objects (such as science fiction posters and video game boxes) would reduce women's interest in studying computer science. These masculine objects, the authors argued, signaled to women that they didn’t belong in the field, which made them less interested in it, and then in turn perpetuated the disproportionate representation of men in the field.

A similar (and more recent) study by Alison Tracy Wynn and Shelley J. Correll of Stanford University calls this a “chilly climate” and examines it in the context of recruitment sessions. Specifically, their observations of recruitment sessions showed that men presenting at these sessions, in an attempt to appear appealing and approachable to an intended audience, reinforced gender roles that may deter women. Although some of these behaviors were relatively innocuous (such as referencing geek culture), they had a distinct impact. Other sessions that took concrete steps to welcome women—such as placing an emphasis on work-life balance and work impacts in the real-world and including women as presenters of technical content—were much more likely to receive questions from women in the question-and-answer session (65 percent versus 36 percent).

This nebulous sense of exclusion may begin even before women enter STEM at all. As Elaine Seymour and Nancy M. Hewitt note in their book-length study of attrition in STEM undergraduate programs, the processes and norms of STEM education were designed for a specific group (white men). Women and students of color who join STEM programs may lack experience with or prior knowledge of the expectations and systems that STEM education uses. Specifically, an emphasis on competition and the use of the “weed-out” system may be disproportionately discouraging to women.

This link between competition, science and technology, and exclusion of women has been shown by Christina Dunbar-Hester of University of South Carolina, Annenberg, to extend to informal settings as well. In her case study of an FM radio tinkering group, she describes how even the group—which explicitly aimed to be inclusive to women—inadvertently alienated its women participants by emphasizing displays of bravado. The women, despite their desire to participate and the men's desire to include them, were put off by a culture that emphasized competitive knowing.

Given that these behaviors and characteristics seem almost laughably minor—Star Trek posters and bragging while tinkering? Really?—it’s fair to wonder how the impact can be so outsized. And it is outsized: As Mary Frank Fox and her coauthors summarize, women in the United States remain underrepresented in STEM doctoral studies, the STEM workforce, tenured or tenure-track STEM faculty positions (yet overrepresented in non-tenure-track positions), and receipt of STEM prizes. Women in STEM publish fewer papers than their male peers, receive less start-up funding, apply for and have lower success rates at receiving grants, and have, on average, lower salaries.

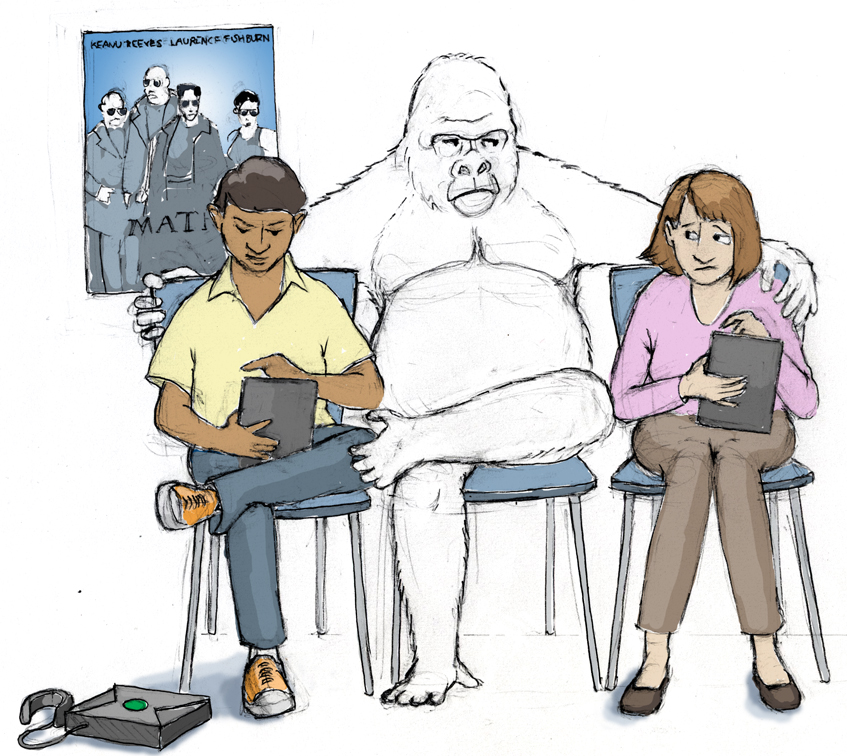

Disconcertingly, a study by Elaine Howard Ecklund and colleagues suggests that men and women scientists may perceive the causes for these imbalances very differently, with women being more likely to point to discrimination as a cause. This discrepancy suggests that gender discrimination may be like the famous invisible gorilla of selective inattention fame: While men in science are able to focus on their work, that focus keeps them from noticing the sometimes subtle and sometimes not subtle discrimination against their women colleagues.

This literature raises what should be a simple question: Given that the exclusivity of STEM is so amorphous, what can anyone do about it? I have two suggestions to offer.

First, separate intent and impact. It’s highly unlikely that the recruiters mentioned in Wynn and Correll's study looked themselves in a mirror before getting on stage and thought, “What's the best way that I can discourage women?” Yet the study shows that women were discouraged, and although the behaviors discussed in the paper are relatively minor, I would suggest the response from these women wasn’t unreasonable. As a metaphor, think of sexual harassment as a hot stove. Once burned, anyone would be reluctant to test empirically whether hot stoves always cause intense pain and tissue damage. In this analogy, these minor exclusionary behaviors aren’t the hot stove—but they may be the "burner on" indicator light, or even the faint smell of gas. They suggest an atmosphere in which more extreme behaviors are more likely to occur, and those are atmospheres that, quite reasonably, a woman scientist may choose to avoid so that she doesn’t incur the risk.

This point brings me to my second suggestion: It’s not enough to do nothing. STEM institutions are built institutions, and, like any physical infrastructure, they were built with certain purposes and users in mind. Consider, for example, a webpage. A webpage is designed for, designed by, and validated on certain kinds of people. This design brings with it a certain set of assumptions about what resources the users would have available—such as what browser they would use, what screen size they would have, and so on. Yet outside of those specific requirements designed for those specific users, things can get messy, or even break. Although the same page goes out to each user, the experience is very different—and if you're already operating the way the designers thought you would, you may have no idea there’s a problem. But rewriting the page with accessibility in mind can solve the problem and make the experience equitable for everyone. Similarly, STEM education (particularly higher education) comes from a long tradition that was historically restricted to certain kinds of people, such as members of the clergy in the early days of universities and, later, members of nobility who had the credentials to join institutions such as the British Royal Society. While there are certainly isolated exceptions, Western institutions have, compared to the history of higher education, only relatively recently begun admitting diverse populations, including women. In light of this, it isn't surprising that the bugs are only now becoming apparent, even if they aren't equally apparent to everyone.

If the National Academies study shows anything, it's that right now, things aren't equitable for everyone. Until science deals with that fact, we’re all going to be stuck with the gorilla.

Bibliography

- Cheryan, S., et al. 2009. Ambient belonging: How stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97:1045–1060.

- Dunbar-Hester, C. 2008. Geeks, meta-geeks, and gender trouble: Activism, identity, and low-power FM radio. Social Studies of Science 38:201–232.

- Ecklund, E. H., et al. 2012. Gender segregation in elite academic science. Gender and Society 26:693–717.

-

- Fox, M. F., et al. 2017. Gender, (in)equity, and the scientific workforce. The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. U. Felt. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press: 701–731.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Seymour, E., and N. M. Hewitt 1997. Talking about leaving: Why undergraduates leave the sciences. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

- Wynn, A. T., and S. J. Correll. 2018. Puncturing the pipeline: Do technology companies alienate women in recruiting sessions? Social Studies of Science 48:149–164.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.