A 3D Twist for Flat Photos

By Natasha Kholgade Banerjee

Manipulating digital photos to fill in their missing parts could be useful in everything from furniture design to accident scene reconstruction.

Manipulating digital photos to fill in their missing parts could be useful in everything from furniture design to accident scene reconstruction.

DOI: 10.1511/2016.119.90

The use of photo-editing applications, such as Photoshop, has become widespread in consumer photography. They have allowed everyday users to circumvent the constraints of a camera by providing the means to change image colors, move pixels around, and combine natural photographs with artificial elements. In doing so, they have greatly expanded the capability of users to express their imagination.

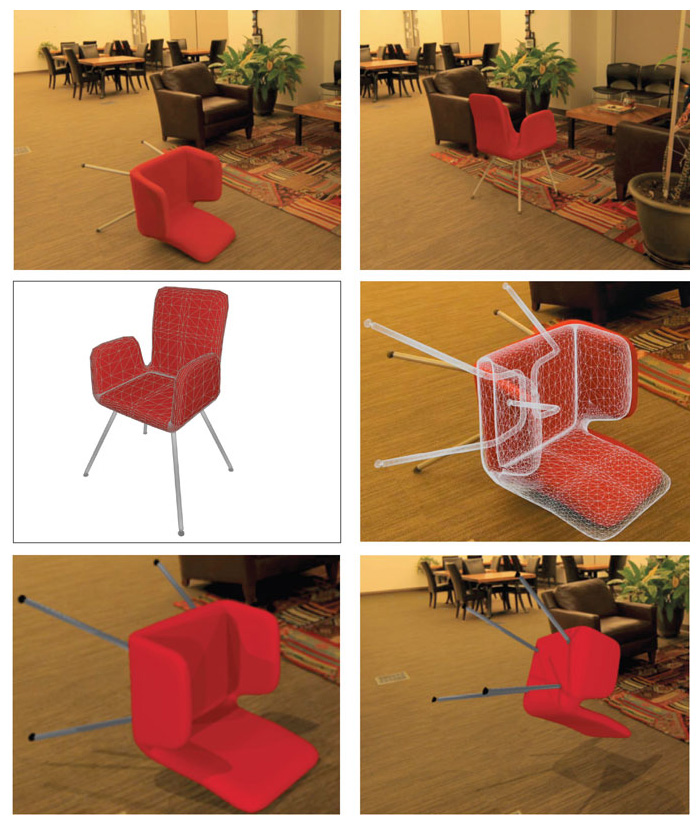

However, traditional photo-editing applications are largely restricted to the two-dimensional view of the objects shown in the image. A chair fallen on the floor in a photograph (shown below) cannot currently be virtually lifted, flipped, and repositioned next to the sofa. Such three-dimensional control of objects is intuitive to humans, as we have a lifetime of real-world experience with handling objects in 3D. But photo-editing software lacks knowledge of the 3D elements in the underlying scene—the geometries and colors of unseen aspects of objects, the locations and intensities of light sources, the optics of the camera—and only knows the 2D pixels in the photograph.

Unless otherwise specified, all images are courtesy of the author.

One way to gain 3D control over objects in photographs is to use computer-aided design (CAD) software to model objects and lighting in the scene. But that’s a challenging endeavor. Imagine having to replicate the detail of a living room—the undulations and woolen texture of a sofa, the wrinkles on the cushions, the stains on the coffee table, the curvature of the armchair, the graininess of the carpet, the ornate flower vase, the window mesh with its wear and tear, and each leaf on the trees outside the window—simply to mimic a photograph! Visual effects companies do recreate entire scenes in 3D to generate special effects, but they use teams of experts, multiple takes, and specialized equipment. Such an endeavor is well outside the scope of the everyday user.

Instead, with the goal of providing full 3D control to users, researchers such as myself are focused on figuring out how to automatically infer the 3D structure of relevant parts of the scene behind the photograph. To flip the chair in the photograph above, the software needs to infer the 3D structure of the chair and the floor, including their hidden surfaces, so that the user can reveal hidden parts of the chair while maintaining shadows and shading over the chair and the rest of the objects the photograph.

For a chair fallen on the floor in a photograph to be virtually lifted, flipped, and repositioned next to the sofa, the software needs to infer the hidden surfaces and the illumination.

One issue is that there is an infinite number of 3D scenes that can produce the exact same photograph. The chair image, for instance, could be created using a chair with smooth fabric lit from above or a quilted chair with a light near the camera; it could even be created by taking a photograph of another photo. The software needs to infer the scenario most intuitive to humans, the first one, to provide practical object manipulation.

Even when information is incomplete, humans can use their lifetime of experience with objects to instantly hypothesize the full 3D structure and colors of objects in a photograph. We know that the chair must have an even shade of red on the seat, a fourth leg, and an underside designed for sitting. If the software had a proxy for our experience, it could solve the problem, and the user could manipulate the object.

Fortunately, we can appeal to large public repositories of 3D models as a proxy. A 3D model is a mathematical representation of an object that describes its geometry and appearance. For instance, a 3D model of a white side table specifies the dimensions of four long white cuboids for the legs, and one white square slab for the top. Websites such as 3D Warehouse and TurboSquid provide large repositories of 3D models for furniture, vehicles, architectural landmarks, household items, toys, electronic devices, plants, and animals. By tying the 3D model of the object to its photograph, the software can provide 3D control over the object to the user.

One way to use the 3D model is to “paint out” the object in the photograph and replace it with the 3D model. A feature of Photoshop called “Content-Aware Fill” allows users to seamlessly paint in an object’s pixels with content from the background. Object insertion approaches allow users to insert 3D models into a variety of photographs, while allowing users either to manually create shadows or to automatically estimate and apply realistic shadows and shading to the inserted objects. The latter approach is being investigated by David Forsyth and his colleagues at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

However, object insertion approaches do not work for an object manipulation scenario. When the 3D model is superposed onto the photographed chair, the geometry does not line up, and the colors are quite different. Furthermore, the 3D model provides no information about the lighting. To precisely represent the object in the photograph, object manipulation software, such as the one I created with my colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University, needs to correct the 3D model geometry, infer the illumination, and complete the appearance of the object to match the photograph.

The claim may be made that the 3D model is wrong and that one should search for the correct 3D model, but it turns out that mismatches between 3D models and real-world objects are quite common. It is impossible to find the 3D model for every single instance of, say, a banana. Moreover, some 3D models in online repositories are designed by users who may not have access to precise specifications of the objects themselves.

Mismatches between 3D models and real-world objects are quite common. It is impossible to find the 3D model for every single instance of, say, a banana.

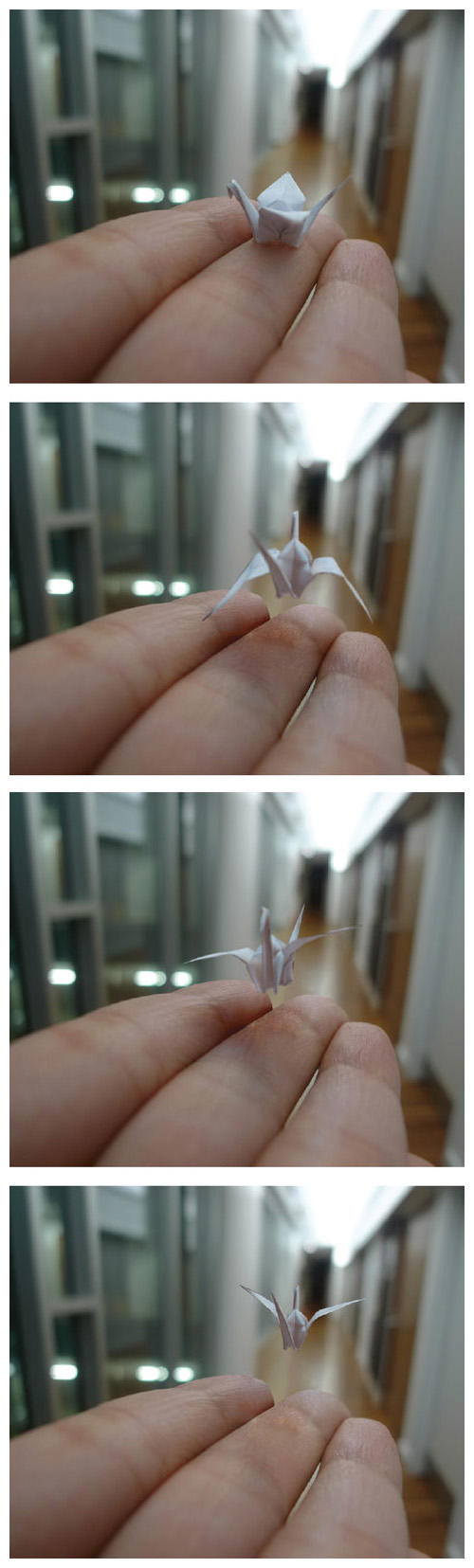

In some cases, a 3D model that is close to the photographed object may be good enough. However, when photographers capture images, they set up the camera, objects, and scene lighting to narrate a story from their imaginations. If the 3D model alters the structure or appearance of the photographed object, it may detract from the originally intended effect. The aim of our software is to maintain the identity of the photographed elements, while providing full intuitive control to the end user to perform adjustments to the orientations and locations in the photograph. Additionally, if the photographer wants to create an animation of the object, such as a flying origami crane, from a single photograph, an imprecise 3D model would introduce an unnaturally sharp break from the original photograph rather than a smooth transition.

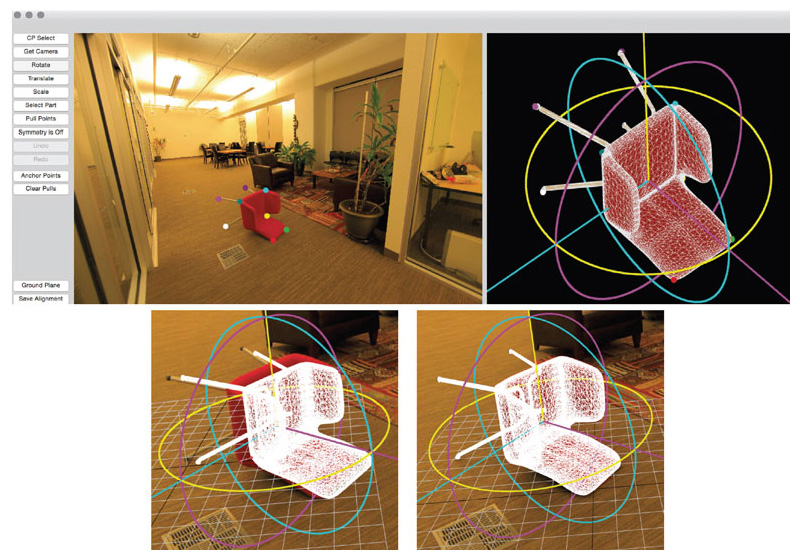

Our software begins by aligning the 3D model geometry to match the object contours. The user loads the 3D model into the application, and provides 2D–3D correspondences between the photographed object and the 3D model— essentially guiding the software with confirmed reference marks for each element of the object. From these marks, our software estimates the location and orientation of the 3D model in the scene underlying the photograph using an algorithm called Perspective n -Point, developed by Pascal Fua and his colleagues at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland. The algorithm determines the rotation and superposition of the 3D model that best matches the superposed 3D points with their 2D counterparts.

Next, the user moves points on the superposed 3D model to line up with the object contours in 2D. Our software uses optimization to determine the best deformation of the 3D model to match the user-provided 2D points, and maintains symmetries and smoothness over the 3D model. A number of objects, such as chairs, tables, vehicles, lamps, stuffed toys, and animals, have a principal plane of symmetry, called the bilateral plane. The optimization ensures that symmetric 3D points on the original 3D model remain symmetric across a bilateral plane in the deformed 3D model. To keep the 3D model smooth, the optimization ensures that as a user moves a point, neighboring points move with it so that the smoothness—represented by displacements between points and their neighbors—is similar to the smoothness of the original 3D model.

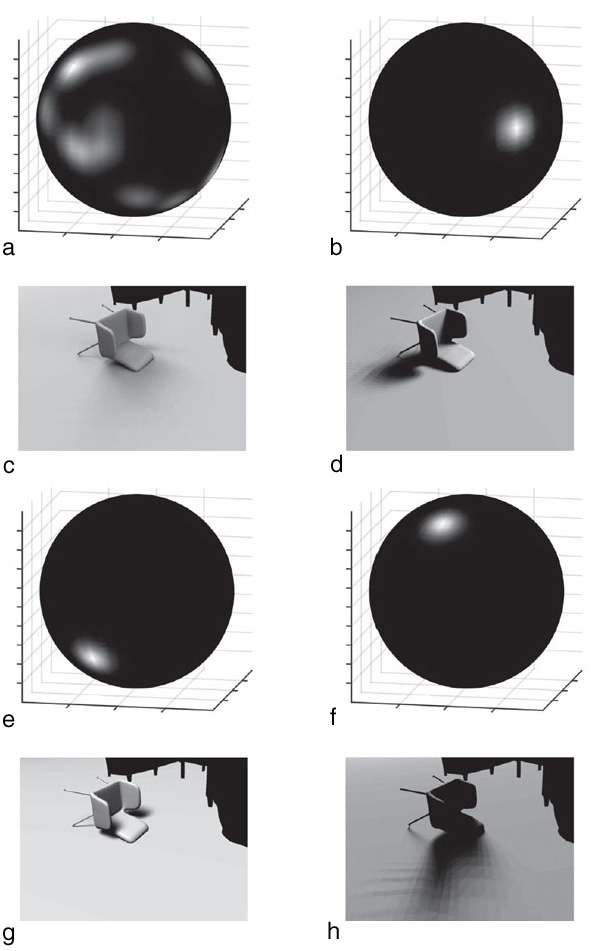

Once the geometry has been aligned, our software estimates the environment illumination as a 3D environment map . As shown in the figure above, an environment map is a sphere that represents how much light arrives at the scene from all directions. Lighter areas of the map indicate a strong light source, such as the fluorescent lights at the back of the room. Dark areas indicate weak or no light sources. Medium intensity sources represent light reflected from white walls. Applying the environment map to the objects and background in the scene creates the shading and shadows in the photograph.

To estimate the environment map, our software probes the scene behind the photograph using a set of what are called von Mises-Fisher kernels. One may think of a von Mises-Fisher kernel as an 8-ball with no 8 on it, and the dot smoothed out. Each kernel is obtained by rotating our modified 8-ball in various orientations. The software estimates the intensities in the map by estimating the best scalings of these kernels and then summing the scaled kernels. A high value of a scale factor represents high light intensity.

For example, the first kernel in the figure above probes the quantity of light to the right of the object, or the shadow intensity to its left. The last kernel probes the light behind the object, or the shadow intensity in front of it. By combining multiple scaled kernels with the photograph, the software automatically deduces that either the last kernel has a small scale because there is almost no shadow in front, or several large lights are on top because there is a strong shadow under the chair.

Again, we use optimization to determine the values of the scale factors that match the environment illumination to the photograph. The optimization algorithm used is often called inverse rendering. The process of rendering provides an end image, given that we know the scene illumination. Thus, inverse rendering provides the unknown scene illumination, given that we know the end image—in our case, the photograph.

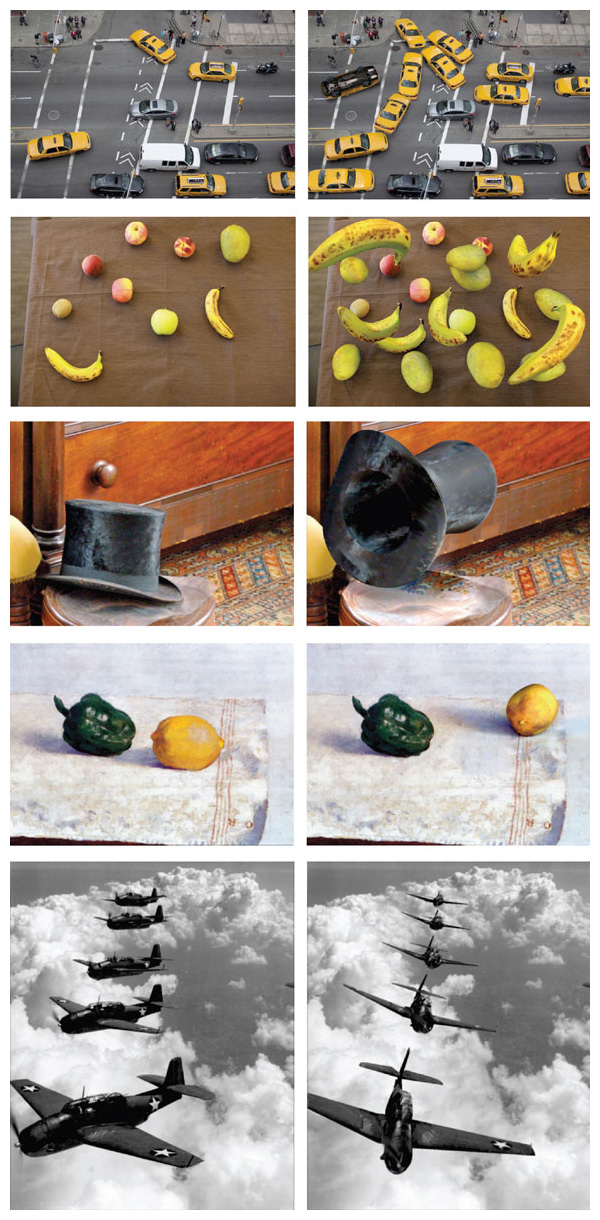

Photos courtesy of (top to bottom) Lucas Maystre/Flickr; author Natasha Kholgade Banerjee; tony_the_bald_eagle/Flickr; Wikimedia Commons; Naval Photographic Center, Department of Defense.

As a by-product of the illumination optimization, our software provides the illumination-independent appearance, or the true color of the object without shadows. To provide a full range of 3D control over the object, the software needs to complete the appearance of the object to include its parts hidden from view. In this way, the software can apply the 3D illumination to the true color of the object to produce perceptually plausible shading and shadows, regardless of what novel parts are revealed.

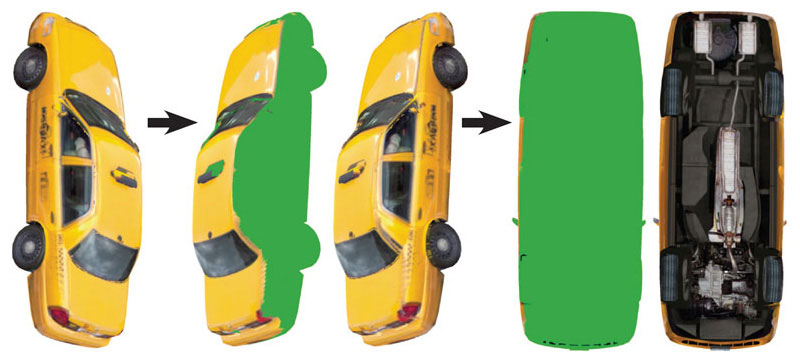

Our software uses symmetries over the object surface to give a complete appearance to hidden parts of the object. The left side of the chair is exactly symmetric to the right side of the chair, according to the bilateral plane of symmetry. Although the back face of the chair is not exactly symmetric to any part, it is approximately symmetric to the front face of the chair back. Humans are fairly accurate at detecting exact and approximate symmetries. Our approach provides appearance completion consistent with the human expectation of symmetry by first estimating a large number of symmetry planes on the object, both exact and approximate, then reflecting the appearance from the visible parts of the object to hidden parts across each symmetry plane to create appearance candidates, and finally stitching the appearance candidates over the object in 3D.

We perform appearance stitching at transitions where adjacent points on the object get their appearance candidates from multiple symmetry planes. The idea of the stitching is to select the smoothest possible transition—that is, the two appearance candidates (out of potentially several dozen) that look as much alike as possible. We perform this choice of transition using a process called graph inference. The software sets up a graph that links appearance candidates, and uses a variant of the shortest-distance algorithm to compute the path with the smallest sum of distances between appearance candidates. For parts of the object that lack exact or approximate symmetries, such as the underside of the taxi as shown on the above, our software stitches in the appearance directly from the 3D model.

Once the software completes the appearance, the system is ready for object manipulation. Our system has re-imagined traditional 2D photo-editing operations as manipulations in 3D, such as rotations, translations, object deformations, and 3D copy-paste. As shown on the opposite page, users can now manipulate objects to create traffic jams with flipped cars, or they can suspend fruit in mid-air. If users desire, they even have control over changing the identity of their objects—for instance, they can transform a top hat into a magician’s hat.

Users can also manipulate objects in non-photorealistic media such as paintings, or in historical photographs of scenes or objects that no longer exist and thus cannot be accessed.

By providing a 3D representation of scenes, our software has allowed everyday users to explore their creativity by tying photographs to 3D modeling software to produce animations, such as the flying crane (above). We also foresee that tying object manipulation to 3D modeling software opens up interesting applications. For instance, we see possibilities in photorealistic accident or crime scene simulations. The software could also help in furniture design and rearrangement for home staging. It could even be useful in organ reconstruction for surgery. And with the rising prevalence of rapid prototyping, the software could help consumers direct construction or 3D printing of everyday objects from photographs.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.