Slipping Past Cancer's Barriers

By Mauro Ferrari

Targeted capsules can find the disease even when it hides in biological bunkers.

Targeted capsules can find the disease even when it hides in biological bunkers.

DOI: 10.1511/2013.105.430

Long gone are the days when cancer was believed to be a single disease, perhaps with varied manifestations in different body organs but otherwise fundamentally the same. Nowadays oncology textbooks report more than 200 cancer types, with a diverse spectrum of diseases even within individual organs. A seminal paper titled “The Hallmarks of Cancer,” published in 2000 by Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg, reframed much of the discussion. In response, oncologists have shifted toward defining cancer by way of its properties—the characteristics that are common to all forms of the disease, and so form broad targets for treatment.

These hallmarks include their ability to invade adjacent tissue, and also set up colonies (or

metastases) at distant sites in other organs; their callous indifference to the molecular screams of neighboring cells that are squeezed by their growth; their ability to evade the immune system and continue on their path of destruction; and their perennial Peter Pan complex—refusing to grow old and die, instead developing the ability to replicate indefinitely and avoid the normal preprogrammed cellular suicide (or

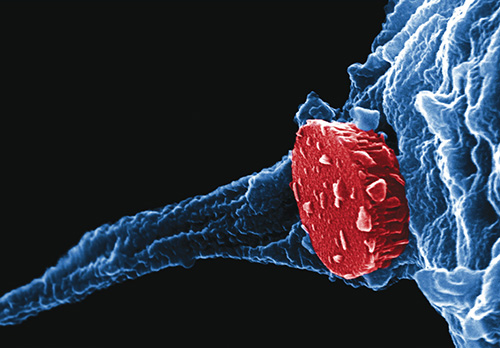

Image courtesy of Rita E. Serda and Jeffrey Li.

In my group’s laboratories and elsewhere, researchers have found that cancer has another extremely nefarious ability: It can protect itself by hijacking the body’s biological barrier system, establishing protective bunkers that shield it from attack by drugs and the body’s own defenses. More generally, the way that cancer transports around substances with mass—molecules, cells, and even tissue—is quite different than what healthy cells do. In some ways all of cancer’s hallmarks are influenced, if not fully determined, by these mass transport differences, both at the molecular and the cellular level, as well as at locations near the tumor and elsewhere in the body.

Based on this observation, my colleagues and I have introduced the notion of transport oncophysics, and we now look at cancer as a proliferative disease of mass-transport dysregulation. We are using new technologies to understand how cancer hides and to break open these bunkers. One of the most promising approaches is targeting cancer with nanoparticles: multilayered, microscopic vessels that could attack a cancer even if it is hiding behind a series of barriers.

The current state of cancer treatment can tell us about how the disease operates, and why mass transport is such a key factor in cancer progression. Much clinical progress has been recorded for several cancer types, especially in those for which oncologists have developed broadly deployable screening techniques. Pap tests for cervical cancer, mammograms for breast cancer, and colonoscopies for intestinal cancer have substantially reduced the burden of death and suffering for these three manifestations of the disease. Unfortunately, there are no equivalent early screening techniques for cancers of the lung, ovary, brain, pancreas, and liver, to cite a few of the most deadly tumor types.

When cancer is detected early enough, it can often be completely cured by surgical removal or radiotherapy. If it is not destroyed in time, however, eventually most primary tumors will send their envoys to establish a metastatic colony in a distant organ—and usually by the time we detect the first metastasis there are many others in multiple body locations. At that point the cancer is generally incurable. With recent advances in chemotherapy and biological therapy (which stimulate the immune system to attack cancer), doctors can extend a patient’s life by weeks or months, and protect the quality of life as well, to a minor extent. But the sad reality is that the current cure rates for metastatic disease still sit where they have been throughout the history of humankind—in a neighborhood near zero.

The central reason for this agonizingly slow progress is that metastases are exceedingly difficult to treat. Surgery is ineffective against them, because of their sheer numbers. Cancer specialists often do not even know where all the metastases are in the body: Radiological imaging reveals some of them, but usually there are many more than can be detected. They may be just too small to be seen by our instruments at the time we run tests, but they will grow rapidly, sometimes in a matter of weeks.

Above all, metastases are diverse. One might think that a breast cancer metastasis to the lungs should be similar to the primary tumor, and respond to the same drugs. This result is sometimes the case, but many times it is not, and over a sufficiently long period of time there always are metastases that share little with their tumor of origin.

Cancer is genetically unstable by its very nature: The daughter cells of a cancer carry a large number of genetic mutations, so their entire progeny has a devastating spectrum of differences that include their vulnerability to drugs. Therefore, when we use a medication that was effective against the primary tumor, we may initially succeed in controlling the metastases, but over time the cells that have a reduced response to the treatment will take over and cause the near totality of cancer deaths. That limitation is one of the reasons my colleagues and I started looking for a fundamentally different way to attack and defeat cancer.

Like metastases, another key issue in cancer’s tenacity is the way that it “builds bunkers” to protect itself. There are many biological barriers in the body, and they can work in series, nesting within each other. All are subject to modifications in the process of cancer development. For example, as cancers grow, their internal hydrostatic pressure increases, opposing penetration into the tumor of drugs that circulate in the bloodstream. In addition, many cancers, including the high-mortality carcinoma of the pancreas, deploy a thin capsule of fibrous tissue around themselves, which is nearly impassable for medications. It is perhaps not surprising that most patients with an inoperable form of this pancreatic cancer survive less than six months from diagnosis.

Cancer also presents biological barriers at the individual cell level. Protective membranes can envelop the entire tumor cell, or its nucleus, or the vesicles that transport many drugs inside the cell. Even reaching the right cell with an exquisitely targeted drug is completely ineffective, therefore, unless the drug can get through those vesicles. Similarly, gene therapy requires that the nuclear membrane be breached.

As a cancer patient undergoes treatment, the challenges often get worse. The cells that repopulate cancers after chemotherapy generally are the hardiest survivors; they have an enhanced ability to expel substances toxic to them through particularly effective pumps in their membranes that push out ions and molecules. These cells stay dormant while the chemotherapeutic assault is raging, insulating themselves from injury, and then can reemerge after the storm and quickly regrow a new, often stronger cancer lesion. Having the right drugs is a good thing, but without delivery mechanisms that can overcome cancer’s formidable sequence of biological barriers, the drugs are limited, and will always be ineffective at eradicating metastatic disease.

The genetic diversity of cells in metastases ensures that cancer’s protective bunkers come in a large variety of forms as well. The chemical weapons that oncologists have to pierce and destroy one bunker many times will not harm most of the other barriers at all. Researchers have many drugs that work perfectly well against cancer cells in a cell culture dish, yet prove largely ineffective in clinical trials with patients.

New imaging tools can let us see how drugs penetrate into cancer lesions in living animal models of human cancer. When researchers, including myself and my colleagues, first did these experiments, we were initially surprised that drugs seemed to enter certain metastases, but not others, even in the same organ, although they came from the same primary tumor. But we have since found that this outcome is the almost universal norm.

These discoveries led me to a radical thought: It is not new drugs that we need, but profoundly new methods to make sure that the therapeutic agents (possibly even including some that had been discarded as failures) get into metastatic lesions and complete their job.

I do not believe that “curing cancer” will be possible unless we solve the problem of achieving effective mass transport against the diversity of biological barriers that cancer can build. So my colleagues and I have set out on this new approach, looking beyond better drugs and instead focusing on better ways to get them where they are needed.

Taking a fresh approach to fighting cancer forced me and a number of other researchers to look beyond the traditional world of oncology. The understanding of cancer growth dynamics, the mechanisms by which it diversifies, and its preferential adaptation of biological barriers and transport modes are generally the province of cancer biologists. Such researchers are used to working with pharmaceutical scientists in the development of suitable therapeutic agents. But expertise on the topic of mass transport generally resides within very different fields: physics, chemistry, mathematics, and engineering. Researchers in those fields also harbor the skills required to design, manufacture, and test synthetic vectors that could deliver therapeutic payloads to a diversity of cancers inside their protective barriers. That cross-disciplinary approach is known as transport oncophysics.

It is not new drugs that we need, but profoundly new methods to make sure that the therapeutic agents get into metastatic lesions and complete their job.

There is a great opportunity for progress against cancer by redrawing the boundaries of science—which are most generally detrimental to breakthrough thinking anyway—and forming interdisciplinary teams, at the service of the clinician in the fight against cancer. Cancer is a disease of physics as much as it is a disease of biology. We need to counter it with a matched array of synergistic weapons.

One of the most important of these new weapons is nanotechnology, which involves devices at a scale much smaller than even the vesicles on cells. At the nanoscale, the distinctions among scientific disciplines are blurred; chemical and physical properties are related in ways not found at larger scales. This is also the scale at which the most basic mass-transport processes operate. Conceptually, then, nanotechnology is a promising domain in which to search for solutions in the delivery of agents to cancers.

Actually, the first nanodrugs entered the clinic about 20 years ago, long before the words cancer and nanotechnology were explicitly uttered in the same sentence. Those early nanodrugs were not identified as such by their creators, but they were based exactly on the notion that biological barriers protecting Kaposi’s sarcoma and metastastic breast and ovarian cancers are altered as the disease progresses.

In particular, the walls of the blood vessels feeding these tumors become more leaky, by way of the presence of gaps (or fenestrations) in vascular tissue. Several pioneering laboratories manufactured lipid-based nanoparticles (called liposomes) to exploit these vascular wall alterations. The liposomes were shown to deliver drugs preferentially to tumors in their angiogenic growth phase, while reducing the adverse action of the payload drug on healthy tissues. Liposomal formulations of drugs such as doxorubicin have since been used to treat thousands of cancer patients worldwide, based on this precursor principle to transport oncophysics, and have become one of the first mass-produced nanotechnologies.

Several other types of nanodrugs have since entered the cancer clinic—including nanoparticles made from the protein albumin and loaded with one of the current principal cancer drugs, paclitaxel—for the treatment of breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. In 2001, German researcher Andreas Jordan of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin developed a new type of nanoparticle made from iron oxide, which does not carry a drug but is itself used as a heat source to cook away certain brain cancers. The iron nanoparticle binds to a specific cancer tissue, then an external magnetic field selectively heats them to kill the tissue. They are the first clinical example of a completely physics-based nanotherapy.

Despite their intriguing potential, none of the nanodrugs approved for clinical use to date possesses any means of molecularly recognizing cancer cells. Their ability to concentrate at cancer sites depends entirely on the mechanisms of preferential transport. There has been great interest in adding cancer-recognizing molecules to the surface of barrier-busting nanoparticles, to give them a targeting specificity. These efforts have featured antibodies, aptamers (nucleotides or peptides that bind to a specific molecule), and various biomolecular ligands (a type of chemical group), attached to the surface of many different nanoparticle types. But despite more than 20 years of work by many laboratories, no biomolecularly targeted nanoparticle has been approved for clinical use.

One fundamental reason for these failures is that the addition of surface modifiers generally renders the nanoparticles less likely to penetrate the cancer bunker—again a matter of transport across biological barriers. The development of effective new therapies requires a deep understanding of biobarriers, because they are the mechanisms that determine how drugs distribute in the body, much more so than the biological recognition afforded by cancer-recognizing molecules.

The importance of biobarriers in cancer treatment led me to a startling thought: Perhaps the bunker itself is the cancer.

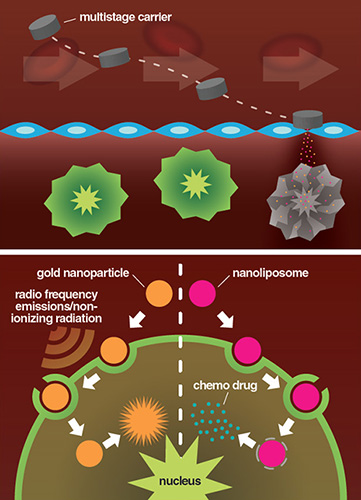

Illustration courtesy of Matthew Landry.

Diversity even within the same type of cells is a powerful mechanism of adaptation that confers major evolutionary advantages. The population of nominally identical cells that line the intestines modify themselves in response to a sustained change in diet, whereas those that form the skin respond to weather and environmental changes, and those in charge of repair following trauma reflect the nature of the injury. These adaptive modifications encode mass transport—what supplies enter and exit different body regions, in what amounts and rates—and extend beyond the cell level, to subcellular transport on one side and tissues and larger biological organizational scales on the other.

Cancer perhaps is a pathological presentation of these processes, the embodiment of the notion that too much of a good thing (such as healing from wounds or responding to environmental changes) can be detrimental to the organism as a whole. In this sense, perhaps cancer is not pathological on the scale of a large population; maybe it is the price that we as a species have to pay to be able to thrive and survive in milieus and conditions that require adaptability in how our body’s cells transport supplies and waste. Until, that is, we take control of our own evolution by developing treatments that allow us to keep collecting the benefits from the body’s adaptive transport mechanisms while effectively avoiding the suffering and death that result when they go awry.

Widely interdisciplinary teams are emerging to establish novel approaches to the treatment of metastatic cancer, and they seem to be keeping biological barriers in mind. We are now seeing the emergence of multistage cancer drugs, with each stage designed to traverse one or more biological barriers. In our laboratory, we have employed this approach to treat animal models of metastatic ovarian cancer and breast cancers with metastases to the lungs. In both of these new treatments we used multistage vectors, with the outer stage of delivery device made from a nanoporous silicon particle that harmlessly dissolves in the body after delivering its therapeutic payload.

For lung metastases, the first stages of these vectors were designed with physical properties (size, shape, surface charge) that maximized their concentration in the lungs. There, they released pDox, a polymer formation of the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin. Upon release inside of the tumor, pDox broke apart into nanoparticles, which were taken up by the target cells and carried by the cell’s vesicles to the vicinity of the nuclei. That location is where the drug is most effective, and the molecular pumps of the cell cannot expel the chemotherapy as efficiently. This combined treatment system resulted in the complete cure of about 50 percent of the animal models, and a great improvement in their survival times. The multistep action system is certainly complex, but no subcomponent of this process suffices to treat these metastases—and neither can anything else ever tried before.

The multistage vector system employed for treating ovarian cancer used nanoliposomes as the second stage and delivered a double dose of therapy: In addition to a conventional chemotherapy, paclitaxel, they also contained a small interfering RNA (siRNA). These short double-stranded RNA molecules are designed to interfere with the expression of specific genes. The multistage vector protected the siRNA from degradation in the body, and provided several weeks of sustained delivery of the therapeutic agent. This approach resulted in the complete remission of metastases in the peritoneum from the ovarian cancer. Again, a multistep solution worked for a problem that did not yield to single-step approaches.

Also promising are new molecularly targeted approaches, which have transformed cancer chemotherapy, and they are particularly promising when researchers can find a companion biomarker that measures the efficacy of the treatment for individual patients. The physics-based counterpart of the biomolecular approach to personalized precision lies in a combination of high- resolution medical imaging and engineering specific nanoscale vectors to transport cancer therapies. Innovation in imaging technology is making it possible to detect and quantify the modalities of mass transport in individual tumors. Using this information, researchers can use mathematical modeling to match an optimal nanovector with a target lesion.

With a combination of advances from different domains of science, I believe it will be possible to realize the century-old “magic bullet” vision of German physician and chemotherapy pioneer Paul Ehrlich, who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1908. Now, as then, the goal is to obtain the greatest therapeutic benefit with the least adverse side effects. If the new, targeted nanomedicines succeed, it should then be possible to extend those therapies to treat the myriad diseases, often coexisting in the same person, that we collectively call “cancer.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.