This Article From Issue

November-December 2016

Volume 104, Number 6

Page 329

DOI: 10.1511/2016.123.329

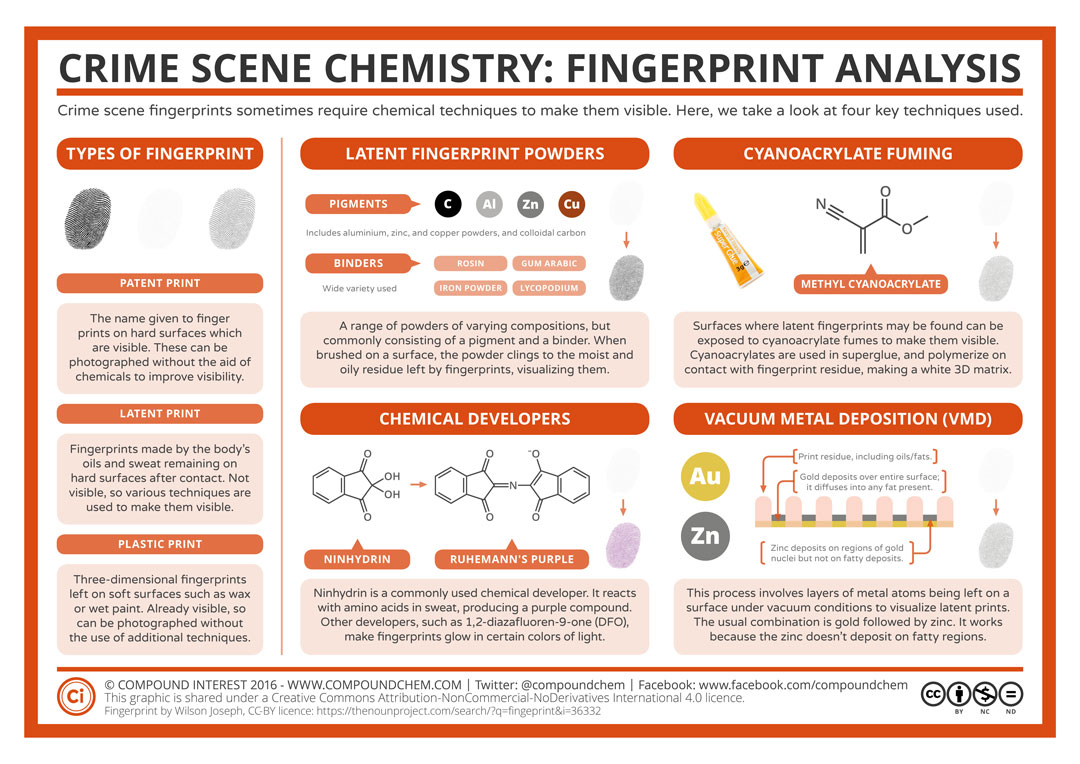

Law enforcement has relied on fingerprint analysis to identify suspects and solve crimes for more than 100 years. Investigators use fingerprints to link a perpetrator to a crime scene. Individual fingerprint identification records have also been used in sentencing, probation, and parole decisions. Officers often rely on chemical techniques, such as those above, to visualize the evidence. However, inadequate proficiency testing of investigators has led to inaccurate interpretations of the evidence. Recent wrongful convictions and scientific studies of forensic methods have increased scrutiny of the validity and reliability of several forms of forensic evidence, including fingerprints. A recent report prepared by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) makes strong recommendations for improving the scientific basis of forensic evidence used in the courtroom. For fingerprinting, the report emphasized the potential for automating fingerprint analysis, to potentially reduce bias in interpreting match results when fingerprints at a scene are smudged or otherwise unclear.

For more information about this infographic, visit http://www.compoundchem.com/2016/07/26/fingerprints/

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.