This Article From Issue

July-August 2006

Volume 94, Number 4

Page 362

DOI: 10.1511/2006.60.362

Extinction: How Life on Earth Nearly Ended 250 Million Years Ago. Douglas H. Erwin. x + 296 pp. Princeton University Press, 2006. $24.95.

Life on Earth has had a bumpy ride. The past half-billion years have witnessed a number of biotic crises of varying magnitude and impact. Probably best known is the end-Cretaceous cataclysm during which the dinosaurs, among other species, died out. However, the most severe event of this type occurred toward the very end of the Permian period, a little more than 250 million years ago, long before the first dinosaurs scampered about: Every ecosystem on Earth was devastated, from tropics to poles, from deep ocean to desert plain. Nine out of every 10 species disappeared forever. It took 100 million years for global biodiversity to return to preextinction levels. The cause of this catastrophe? We are still not completely certain.

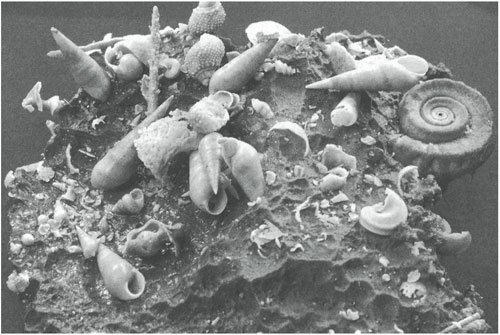

Photograph taken by J. Brooks Knight in the 1950s. From Extinction.

The end-Permian event is currently attracting more scientific attention than ever before. Barely a week goes by without publication of a new scientific article on the subject, and we are at last closing in on the truth of what happened to our planet so long ago. This paleontologic detective story, the patient study required to solve it, and the frustrations, excitement and red herrings generated in the process are all detailed by Douglas H. Erwin in his wonderful new book, Extinction.

Erwin begins his tale in Utah, neatly explaining the severity and importance of the end-Permian crisis by taking the reader on a short field trip to some classic localities that give us "before" and "after" snapshots of the event. He then goes on to explain the layout of the book: It is "written as a mystery story." And indeed, it's a very readable one. The obvious strengths that make it so—the clarity of the writing, the relaxed style, the neat mixture of scientific fact and amusing personal anecdote—come to the fore very early. The mystery begins not with the scene of the crime, or a discussion of the evidence, as one might expect, but with a description of the suspects: the list of possible causes.

This is followed by another field trip, this time to South China, and a review of some of the key research projects Erwin was involved with in the mid-to-late 1990s, which demonstrated for the first time the pattern and rate of extinction. Again, the anecdotes and asides help keep the reader's interest and provide nice little insights into the character of the author and his colleagues. Included in this section is the best explanation of the methods, biases, problems and absolute necessity of geological dating that I have ever read!

Finally we get back to the mystery story proper, with a discussion of what groups actually went extinct. Here Erwin missed an opportunity. In his first book on the end-Permian event, The Great Paleozoic Crisis: Life and Death in the Permian (Columbia University Press, 1993), he described in great detail the extinction patterns of all fossil groups. Since then, there has been a tremendous advance in our understanding of the fossil record, particularly with the publication of new, larger databases of fossil diversity and descriptions of many more species. It would have been nice if Erwin had explored in this new book how the extinction plots of 1993 have changed. But instead he skims over many of the groups affected, and some he doesn't even touch on. For a fuller (though slightly out-of-date) picture, readers should consult his earlier book.

Next Erwin recounts a field trip to South Africa and examines some of the recent advances made in studies of the extinctions on land, with particular reference to the vertebrates. He discusses the vertebrate fossil record and explains how a literal reading of fossil ranges, if it fails to take into account the relationships between the different species, can lead to a false picture of the severity of the extinction. This is a fundamental concept—one that affects all fossil groups, not just vertebrates, and all events, not just the end-Permian crisis. Almost certainly paleontologists have overestimated the magnitude of diversity loss during all past biotic crises through reliance on a literal reading of the fossil record.

Then Erwin briefly returns to the subject of the oceans to discuss Permian marine ecosystems. Here I came across my favorite typo: The coal beds that lie beneath the volcanic Siberian Traps and may be a source of light carbon dioxide mysteriously morph into "extensive Siberian cola beds"—which would almost certainly be a great source of CO2! Next comes a roundup of the evidence and a whittling down of the list of suspects to . . . ah! but I won't spoil it for you!

Then Erwin briefly describes the patterns of postextinction recovery, summarizing some very recent work. The book concludes with a nice, succinct account of how the end-Permian event fits into the evolutionary history of the biosphere and what lessons—if any—we can draw from it that might apply to the present-day biodiversity crisis. Notes, a comprehensive reference list and an index follow.

Overall, Extinction is a very enjoyable read and a worthy follow-up to The Great Paleozoic Crisis. It provides a thoroughly up-to-date account of the causes of the end-Permian event and the developments in the field since 1993 as seen through the eyes of one of the key players. Here and there Erwin is able to put his hands up and admit he was wrong (the sign of a first-class scientist), but in truth Extinction leaves the reader with the (accurate) picture that here is a scientist whose work has significantly advanced our understanding of the greatest extinction event known to science.

Recently, I had the good fortune to bump into Erwin at a conference. I asked him what aspect of the end-Permian problem he was going to tackle next and was somewhat surprised when he answered that he is moving on to other fields of research. "I've said all I want to say [on the subject]," he confessed. I sincerely hope he'll change his mind, as there are few others who have worked so hard and long on this problem. If Extinction really is his last word on the end-Permian event, then this readable and scholarly account is a fine way to bow out. I recommend it to all.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.