This Article From Issue

September-October 2013

Volume 101, Number 5

Page 389

DOI: 10.1511/2013.104.389

HIDDEN BEAUTY: Exploring the Aesthetics of Medical Science. Norman Barker and Christine Iacobuzio-Donahue. 232 pp. Schiffer Publishing, 2013. $50.

The common reaction to disease is to want to look away. The authors of Hidden Beauty make a powerful argument for overcoming that impulse. Many of the microbes and tissues involved in an affliction have intricate structures and captivating forms. View them with modern imaging techniques, appropriately magnified and colorized, and the results can be downright spectacular.

From Hidden Beauty.

In his foreword to the book, cancer geneticist Bert Vogelstein of Johns Hopkins University notes that aesthetics are traditionally something of an afterthought in medical imaging. The primary goal is to efficiently relay diagnostic information, such as the presence of a tumor. But capturing the details of a disease can create visual interest all the same. As Vogelstein explains, normal tissues are highly organized, but diseased ones break down, creating “random and unique patterns that can be visually appealing.”

If not framed tactfully, the topic of Hidden Beauty could seem to trivialize the suffering of patients. But the authors directly address the strange duality of their topic: Patients viewing diagnostic imagery often face terror and uncertainty, whereas clinicians may find the same images awe-inspiring. Iacobuzio-Donahue and Barker write that “within the most serious, life-threatening, and deadly diseases are aspects that, when taken out of their context, have inherently aesthetic qualities. In no way do we propose that disease itself, or the suffering it creates, is aesthetically pleasing.” (They are well equipped to see things from both sides; Iacobuzio-Donahue is a pathologist, and Barker is an artist who specializes in photomicroscopy.)

In the earlier sections of the book, each chapter is organized around one section of the body, from the head and neck through the pelvis. Later chapters focus on connective tissue and infection and inflammation. Research images (rather than clinical ones) receive their own section as well.

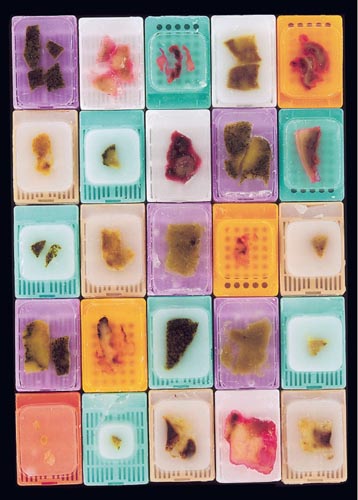

From Hidden Beauty.

The chapter on the chest includes a strikingly colorful image of tissue samples embedded in paraffin blocks designed for pathology testing. As part of the preparation process, the tissues are chemically fixed and dehydrated in alcohol so they can be permeated with hot wax. The purpose is to provide support for the tissues as they are thinly sliced and stained for viewing under a microscope.

Another compelling image, which appears in the abdomen chapter, features a collection of intricate, shell-like structures that are actually gallstones. These solid crystalline deposits form only in the gallbladder but differ widely in composition, resulting in seemingly infinite variety. Elsewhere in the chapter, a cross section of the small intestine captures in iridescent detail the elaborate protrusions, or villi, that line its inner surface and aid in digestion.

Later in the book, a portrait of the liver, looking a bit like a pointillist painting, graphically displays cirrhosis, where fibrous tissues replace healthy ones. The image conveys, in its way, as much drama as a front-page newspaper photo of a boxer’s knockout punch: As healthy cells try desperately to regenerate themselves, they are hemmed in by the fibrous tissue packed around them, so they are forced to form shrunken nodules.

This blending of medical message and visual impact is a recurring theme throughout the book. A lacy network of bone, shown in the chapter on connective tissue, brings alive the authors’ point that bone is not solid and inert but a vital and dynamic organ in its own right. The sponge-like network of tendrils, called spicules, in a femur provides an extensive surface area to make minerals available to the body and to provide a scaffold for bone-marrow cells.

“Photography is not only a system for illustrating science; in many ways it’s also a method for doing science,” the authors write. Acknowledging the aesthetics of disease is another way to understand the workings of the human body and how it can be compromised. Images such as the ones in Hidden Beauty can move beyond the suffering—reaching, perhaps, toward literal and figurative healing.

Fenella Saunders is managing editor of American Scientist, where she covers work in the physical sciences, among other subjects. She received her M.A. in psychology and animal behavior from Hunter College of the City University of New York.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.