This Article From Issue

November-December 2000

Volume 88, Number 6

DOI: 10.1511/2000.41.0

Labyrinth: A Search for the Hidden Meaning of Science. Peter Pesic. 186 pp. The MIT Press, 2000. $21.95.

During the 17th century, in the aftermath of the previous century's great religious schisms and challenges to the traditional frameworks of Aristotle, Ptolemy and Galen, several schemes were advanced regarding the possible relations between science and the Christian religion. One of these schemes adopted the metaphor of two books and regarded God's works (the Book of Nature) and God's word (the Book of Scripture) as equivalent sources of Christian knowledge.

This viewpoint asserted that both books led to the Truth, but that their foundations were, and were to remain, separate, with distinct languages, modes of demonstration and institutional practices. Another scheme, pansophia, attempted to formulate a new Christian synthesis that would meld the canonical and the new knowledge and amalgamate the ministers of religions and of the new sciences into a single body, thus to avert further conflict. The metaphor of the two books proved particularly serviceable and effective, and it made possible the spiritual accommodations required by the advances of scientific knowledge. The separation of the realms of religion and science has remained the predominant rhetorical solution for the problem to our own day.

From Labyrinth: A Search for the Hidden Meaning of Science

Among those writing on the relation between science and religion during the 17th century were the trumpeters of the new science—Francis Bacon, Tommaso Campanella, Jan Comenius and others—not "scientists" themselves, but staunch defenders of the new knowledge and the new practices who drafted ambitious agendas for them. Also partaking in the controversy were the philosophers—such as René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz and John Locke—and the "scientists" themselves—William Gilbert, François Viète, Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton and others.

In his short book, Peter Pesic brilliantly conveys the meaning and motivation for the attempts of Gilbert, Kepler, Newton and the other virtuosi to read the Book of Nature and to decipher her secrets. A sense of childlike wonder propels all of them in their explorations of the mysteries of Nature. But whereas the unimaginability of God remains ever present, Nature at times does allow the unimaginable to become understandable—only to divulge further realms in which to let human imagination roam.

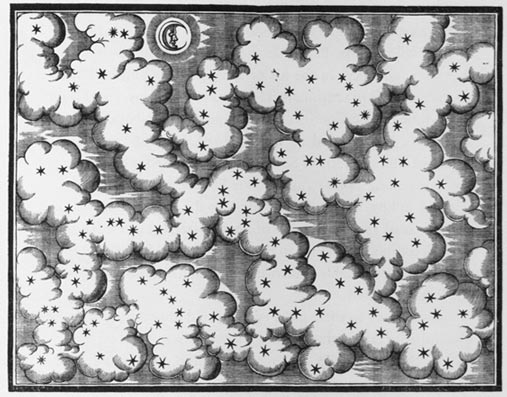

Pesic describes his book as a triple fugue, interweaving three themes: "the arduous struggle between the scientist and nature"; "the effect that struggle has on the character of the scientist, . . . a kind of purification that affects the wellsprings of human desire"; and the crucial emergence from this struggle of symbolic mathematics, the purified language necessary to decode nature's secrets. The stage is set by Pesic's insightful and imaginative analysis of Gilbert's scientific study of magnetism, the role of Viète's code-breaking activities in laying the foundations of modern symbolic mathematics, and the role of Bacon's writings in anticipating the shape of modern science and justifying its mission. The second half of the book concerns the encounters of Kepler, Newton and Einstein "with the depths of Nature."

In his acknowledgments, Pesic salutes Larry Cohen and his associates at the MIT Press for their vision and courage in publishing his book. They are indeed to be commended, for Pesic's little book is a gem. He has succeeded in engaging the reader in a deeply rewarding philosophical quest to uncover the meaning of modern science. He has accomplished this by virtue of his deep erudition, his impressive mastery of the science and mathematics involved, his deeply felt passion, and his lucid, engrossing and captivating expository style. Perhaps in the future he will apply his considerable talents to an exposition of the road taken by Blaise Pascal, the mathematician-turned-Jansenist who denied the worth of the conventional works of a deterministic science and could accept contingency and probabilities, the novel and important facet of modern science.—S. S. Schweber, Physics and the History of Ideas, Brandeis University

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.