This Article From Issue

November-December 1998

Volume 86, Number 6

DOI: 10.1511/1998.43.0

Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics. Peter Galison. 982 pp. University of Chicago Press, 1997. $34.95.

Peter Galison's history of high-energy physics traces the development of particle detectors, instruments that are fascinating in themselves. Galison gives us rich detail, skillfully woven into a smooth and entertaining narrative. The detectors are inherently beautiful—involving subtle craftsmanship and brute-force engineering. But Galison's purpose is not so much the detectors per se as seeing what these devices (which originally cost a few hundred dollars and now cost hundreds of millions) can tell us about physics, physical science and the nature of scientific revolutions. Because these detectors represent in hardware and software what physicists believe about the way nature is constructed, the story of the detectors is inevitably the story of physics itself.

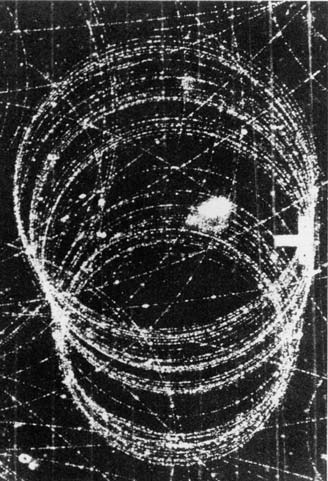

Galison starts with the earliest uses of cloud chambers and Geiger-Müller tubes and follows the field through the development of huge, expensive, complicated devices found at accelerators in the United States and Europe. Galison argues that the detector development proceeded along two distinct paths: the image machines (cloud chambers, nuclear emulsions and bubble chambers) and the logic machines (Geiger counters, hodoscopes and spark chambers). The adherents, traditions and methods for each mark a rich intellectual tradition that persisted over time. More significantly, each path's participants had different views of what constituted compelling evidence for the existence of a particle or phenomenon. The image groups sought golden events, perfect mimetic figures—literal pictures of the entities themselves. One perfect photograph could be conclusive evidence of a new particle or interaction. The logic groups saw nothing in a single event but rather used accumulations of individually meaningless events to form a collection that was itself conclusive. Developments along the logic path involved ever more complicated reasoning about coincidence between ever more complicated arrays of solitary detectors. In the logic world the accumulations were all.

From Image and Logic.

These paths collide in the current generation of detectors where both traditions are combined. These detectors are titanic machines, the largest scientific creations dedicated to the smallest entities. They generate images through logic, using the computer to gather, collate and finally draw pictures based on thousands of discrete, individually meaningless measurements—the mimesis is discarded at first in exchange for a bewildering wave of data but then regained by deliberately assembling and constructing. The scientist synthesizes nature.

This wonderful synthesis is purchased at great cost. The division of labor and deliberate long-term commitments to specific methods and designs that are essential to creating and operating these detectors inexorably led to the deconstruction of physics itself. In a variety of ways, the physicist disappeared into a group that included mechanical, electrical and chemical engineers; administrators and programmers; project planners; and a panoply of technicians. This has called into question what it means to do physics.

Galison's historical view challenges mainstream philosophers of science by noting that the machines and methods produce a continuity that most accounts do not credit. Many experimental techniques, devices, traditions and methods are sustained during transition from the old to the new. Galison argues that the persistence of material, experimental cultures makes it possible for a durable community of physics to exist. This view of experiment, which Galison began in his earlier book How Experiments End, denies both the classical empiricist view that data drives theory and the modern sociological view that theory constrains data. These polar extremes fail to capture the dialectic between theory and experiment. This leads Galison to devise a place for the dialectic which he describes as "trading zones." He reaches into anthropology for this term, which describes areas where new language is developed to permit commerce between cultures that lack a common language. Galison shows how this allows people with disparate roles to create modern physics by delimiting meanings in ways that allow productive work to go forward. This is a powerful idea when applied to high-energy physics, but it will have great impact elsewhere. Such zones exist in the intensive care units of research hospitals and elsewhere.—Richard Cook, Cognitive Technologies Laboratory, Anesthesia and Critical Care, University of Chicago

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.