This Article From Issue

November-December 2004

Volume 92, Number 6

DOI: 10.1511/2004.50.0

Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist Who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell. Eric Enno Tamm. xvi +365 pp. Four Walls Eight Windows, 2004. $26.

Beyond the Outer Shores is a new and welcome biography of maverick marine biologist Ed Ricketts. The title refers to Ricketts's name for the rugged coast of the Pacific Northwest, including Vancouver Island, the Queen Charlotte Islands and the islands of southeast Alaska, and much of the book focuses on the ecological research he conducted there. The book's author, journalist and conservationist Eric Enno Tamm, grew up in a fishing village in the area.

Ricketts is perhaps best known for having been the prototype for "Doc," the central figure in John Steinbeck's novels Cannery Row (1945) and Sweet Thursday (1954). By most accounts the fictional Doc, who loved women, beer and truth, was much like the man who operated Pacific Biological Laboratories on California's Monterey Peninsula from 1923 until his untimely death in 1948.

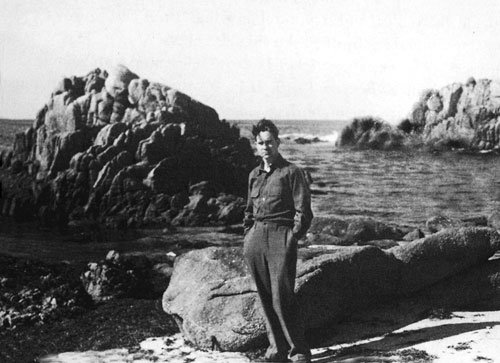

From Beyond the Outer Shores.

Ricketts, who supplied prepared biological specimens to schools, was a gifted field ecologist. His coastal collecting trips led to a seminal book on intertidal ecology, Between Pacific Tides (Stanford University Press, 1939). It went beyond taxonomy to describe intertidal animals holistically, placing them in the dynamic context of their habitat and ecology. Concepts that we now take for granted, such as competitive exclusion, and habitat descriptors such as wave shock, were novel then and seemed to threaten the established order. Ricketts was "a lone, largely marginalized scientist" with no university degrees, and he had to struggle long and hard against the "dry ball" traditionalists of the time just to get the book published. Yet today it is widely regarded as a classic work in marine ecology and is now in its fifth edition.

Ricketts's lab on Cannery Row was a magnet for scientists, writers, prostitutes, musicians, artists, academics and bums. Gatherings there included discussions of the interplay of philosophy, science and art, and often evolved into raucous, happy parties that went on for days.

Steinbeck was a frequent visitor, and Ricketts had a strong humanistic and naturalistic influence on the writer's work in the 1930s and 1940s. Ricketts's persona appeared in several of Steinbeck's most powerful novels, including In Dubious Battle (1936) and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). Steinbeck occasionally referred to himself as a biologist, and ecological themes run through much of his finest work, as Tamm points out. Tamm also notes that except for East of Eden (1952), Steinbeck's fiction and his literary reputation declined after Ricketts's death.

Ricketts was likewise a muse to the mythologist Joseph Campbell, who not only attended parties at the lab but for a time was Ricketts's next-door neighbor and joined him in 1932 on an extended collecting trip along western Canada's Inner Passage. In later years Campbell would refer to those days as a time when everything in his life was taking shape. Tamm writes that Campbell, the great chronicler of the "hero's journey" in mythology, recognized patterns that paralleled his own thinking in one of Ricketts's unpublished philosophical essays. Echoes of Carl Jung, Robinson Jeffers and James Joyce can be found in the work of Steinbeck and Ricketts as well as Campbell.

Steinbeck and Ricketts went on a biological expedition together to the Gulf of California in 1940 and then collaborated on a book about it, Sea of Cortez (1941). It was the second volume of Ricketts's planned trilogy on the intertidal ecology of the Pacific coast. Tamm's coverage of the trip to the Gulf is sketchy, perhaps because he is more interested in Ricketts's research in the north.

In 1948 Ricketts was preparing for an expedition with Steinbeck to British Columbia; the plan was that they would jointly author a third book, The Outer Shores, which would extend their surveys north to Alaska. Ricketts had already completed most of the research for such a book on earlier collecting trips to Vancouver Island and the Queen Charlottes. Following the pattern he and Steinbeck had established in their previous collaboration, in preparation for the new book Ricketts sent him typescripts of his field notes and journals from those earlier trips.

The week before Ricketts was to leave on the expedition, tragedy intervened: As he was driving to get dinner after a long day in the lab, an evening train, the Del Monte Express, rolled through a blind crossing and collided with his car. Ricketts died of his injuries soon afterward.

Steinbeck could not bring himself to follow through on the Outer Shores book after Ricketts's death. Some of the field notes and journals Ricketts had sent him were eventually edited by Joel W. Hedgpeth and published, along with Ricketts's essays, as The Outer Shores (Mad River Press, 1978), which has long been out of print. The typescripts Ricketts had sent Steinbeck provide the heart of Tamm's "odyssey." Ricketts's words are supplemented by information from ships' logs, interviews, letters and Tamm's affectionate descriptions of the settings for what would have surely been Ricketts's most compelling work.

Clearly, Tamm loves this part of the world, and his book is filled with its history and lore. His grasp of ecology is a little shaky, though, and he stumbles occasionally with such topics such as Aristotelian and Linnaean taxonomy, and the beginnings of life on Earth. But no harm is done to the real story.

This is not a full-blown biography. Rather, it illuminates what has been a shadowy but important part of Ed Ricketts's life, and it leaves us wondering what might have been. I liked this book so much that I read it twice.—Bruce H. Robison, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, California

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.