Life on the Red Planet

By Lisa Yaszek

David Baron’s newest book explores how Mars captivated Americans in the early 20th century.

October 30, 2025

Science Culture Astronomy Sociology Astrogeology Review

THE MARTIANS: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America. David Baron. 336 pp. Liveright, 2025. $29.99.

One dying world with squidlike, bloodsucking inhabitants who must invade their closest celestial neighbors to survive. One world where feathered, angelic beings cooperatively transform a hostile landscape into a peaceful, high-tech paradise. And yet another world, where astral travelers cross time and space to pass on their culture’s wisdom to humbly receptive humans. Welcome to Mars, as it was conceptualized by Americans at the turn of the 20th century, a time when science, imagination, and celebrity came crashing together in ways that still resonate today.

Photograph courtesy of Scott Knowles.

As author and science historian David Baron explains in his new book, The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America, the “Mars craze” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries emerged at the intersection of multiple events, including the professionalization of astronomy, the beginning of U.S. imperialism, the rise of sensational or “yellow” journalism, and the emergence of science fiction. Drawing on a combination of newspaper archives, personal correspondence, and on-site visits, Baron relates this tale in three chronological acts. The first part covers the period between 1876 and 1900, and introduces us to the key people, historical events, and technoscientific developments that fostered turn of the century fascination with the red planet. The next section explores how the Mars craze peaked in the opening years of the new century, as scientists debated the possibility of a Martian civilization, journalists and artists dramatized those debates for eager audiences, and everyday people got in on the act by claiming their own psychic and spiritual connections to Mars. Finally, in the third and final part, Baron shows how the Mars craze dissipated when the public turned to new and different forms of entertainment and scientists were wielding advanced imaging technologies proved that the Martian canals were natural features of the red planet. And yet, as Baron reminds us in his eponymously titled conclusion, we are all “children of Mars,” in that the history of our fascination with Mars inspires scientists and science fiction artists even today, in the form of the modern space race and films such as Andy Weir’s novel (and its film adaptation) The Martian.

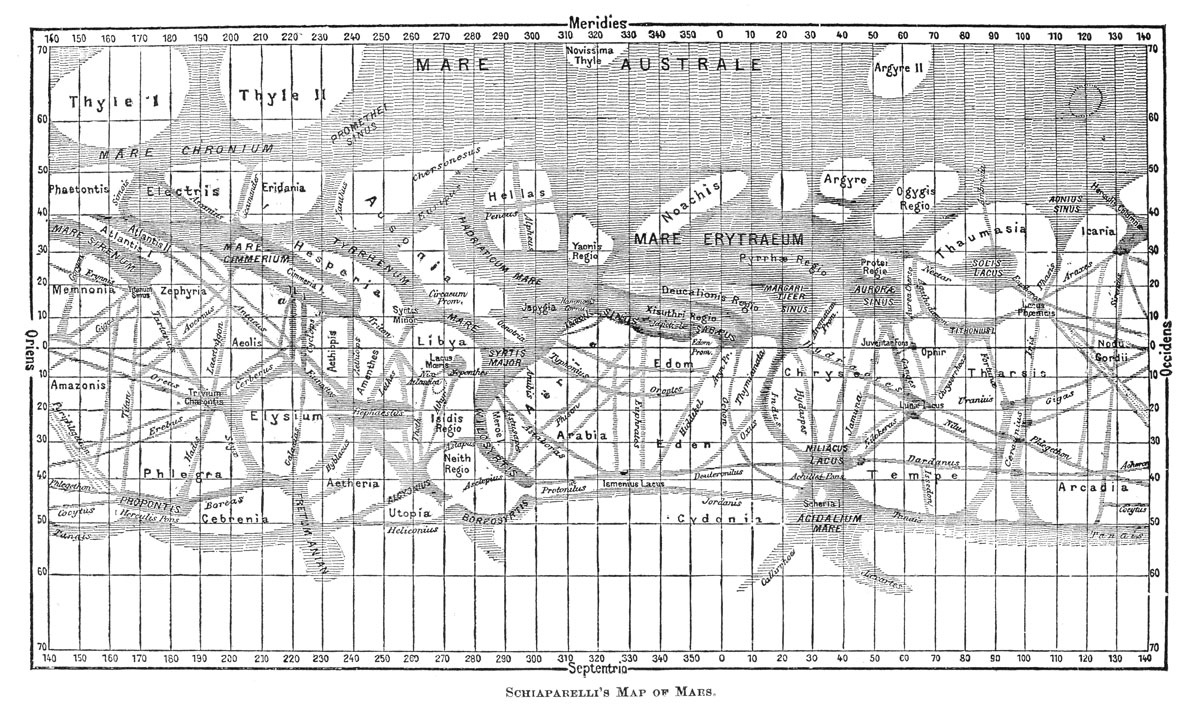

But what makes The Martians particularly compelling is its depiction of Percival Lowell, the American businessman turned amateur scientist who seized upon Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli’s 1877 observation of Martian “canali,” mistranslated into English as “canals,” to popularize the notion that Mars was inhabited by intelligent, technologically savvy beings. Born into an illustrious Boston family, Lowell was never fully comfortable in that society, preferring instead places such as Japan, Korea, and Flagstaff, Arizona—little wonder that he would later claim to be “half-Martian.” At the same time, he was very much a product of that society, driven by a Puritan work ethos demanding that he follow in the footsteps of the Lowell men before him by working hard and leaving a legacy of significance.

For Lowell, that legacy was finding proof of a civilized Mars. A well-spoken, well-connected man who had the money to build his own observatory and buy an MIT professorship, Lowell was also quite media-savvy, speculating about the possibility of Martian civilization with members of the yellow press to drum up public interest in his theories while publishing the scientific evidence for Martian life collected by his observatory in the most prestigious magazines of his day. But the same tenacity that catapulted Lowell to fame would prove to be his downfall. Lowell had long been willing to “select and bend facts” to his pet theories, and by the 1910s, his arrogance led him to dismiss significant new evidence confirming the lack of both artificial canals and intelligent life on Mars. And yet, even as the world moved on from Martian mania, Lowell remained convinced that he was correct and that the kind treatment he received from his professional peers later in life was evidence of their respect for “the Martian ambassador.”

More than just capturing an oddball moment in American history, The Martians is also a serious meditation on the relations of art and science. Baron argues that Lowell was very much an “astronomer poet” who channeled his natural talent and educational training to create a story that captivated scientists, artists, and laypeople alike. Moreover, although his theories of Mars went on to influence the later work of popular science writers and speculative storytellers including H.G. Wells and Garrett P. Serviss, the line of influence was not unilateral. Rather, Lowell’s vision of the red planet was influenced by some of his most romantic fiction reading, including both old tales of alien life written by Western philosophers in previous centuries and new stories of “high adventure at the Earth’s remote outposts” written by modern, commercially-oriented fiction writers—including one of Lowell’s favorite authors, Robert Louis Stevenson.

Indeed, Baron uses The Martians to explore the art of science itself, showing how much turn of the century scientific debate about Mars had to do with the creative interpretation of ambiguous data. Although telescopes of that era were powerful enough to disprove the notion of lunar life, it was still extremely difficult to capture clear images of even the closest planets. Atmospheric interference made it challenging to draw Mars with any real precision. Early photography only made the situation worse: “Mars was tiny and faint, emulsions were slow, and the planet turned on its axis, blurring out delicate markings one might hope to record during a long exposure.” Since photographs of Mars were essentially “indecipherable inkblots,” it was up to experts (and supposed experts) to interpret them—and for a long time, Lowell was the expert. But Lowell’s theories fell out of fashion by the early 1910s, challenged first by the work of Eugene-Michel Antonadi, a European astronomer with superior art skills whose finely detailed drawings indicated that the Martian canals were optical illusions, and then by scientists at the Mt. Wilson Observatory whose high-powered cameras produced images confirming Antonadi’s sketches. Yet even as his professional peers embraced the notion of an arid, uninhabited Mars, the power of Lowell’s story persisted, inspiring a whole new generation of scientists and artists including Robert H. Goddard, inventor of the liquid-fueled rocket, and Hugo Gernsback, publisher of the first specialist science fiction magazine.

The Martians is a richly detailed book that charts the development of our current scientific and artistic ideas about Mars through the story of one man’s personal obsession with the larger universe, along with one nation’s desire to make sense of rapid scientific and social change here on Earth. Baron’s sensitive treatment of Lowell and the Mars craze as a lens through which to understand the multiple, often conflicting forces that shaped turn of the century America is inspiring and thought-provoking.

From some angles, the book might appear to be, as Baron puts it, “a story of human folly [and] how easy it is to deceive ourselves into believing things simply because we wish them to be true.” From other angles, we might pessimistically see it as a meditation on the ability of rich and powerful people to disseminate self-serving and perhaps even dangerously inaccurate “scientific” information through a tabloid media more interested in profit than truth. But ultimately, as Baron himself eloquently concludes, the story of Percival Lowell and the Mars craze provides a more hopeful lesson as well: that “human imagination is a force so potent that it can change what is true”—in this case, inspiring both a real-world space race that spans the public and private sectors and an equally global tradition of speculative and design literature that treats the red planet as the place where we might become our better, higher selves. In other words, where we might become Lowell’s Martians.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.