Escher the Scientist

By Fenella Saunders

The artist M. C. Escher valued the influence of scientists and mathematicians in producing his famous works.

October 7, 2016

Science Culture Art Mathematics Aesthetics

A documentary of Maurits Cornelis Escher made in 1971, recently publicized, has once again raised public perception of this iconic artist. It is ironic that M. C. Escher actively disliked pop culture, as posters of his prints have graced college dorm rooms for decades. He flatly turned down a request from the Rolling Stones to create an album cover for them in 1969. Art critics also seem to have been mistaken about Escher’s desire to popularize his work. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC—which holds more than 400 pieces of Escher’s work in its collection—did an exhibit of Escher’s art in 1998 to celebrate the centennial anniversary of his birth, which was highly popular, but severely panned by the art world as public-pleasing work akin to Norman Rockwell’s illustrations and Pachelbel’s Canon.

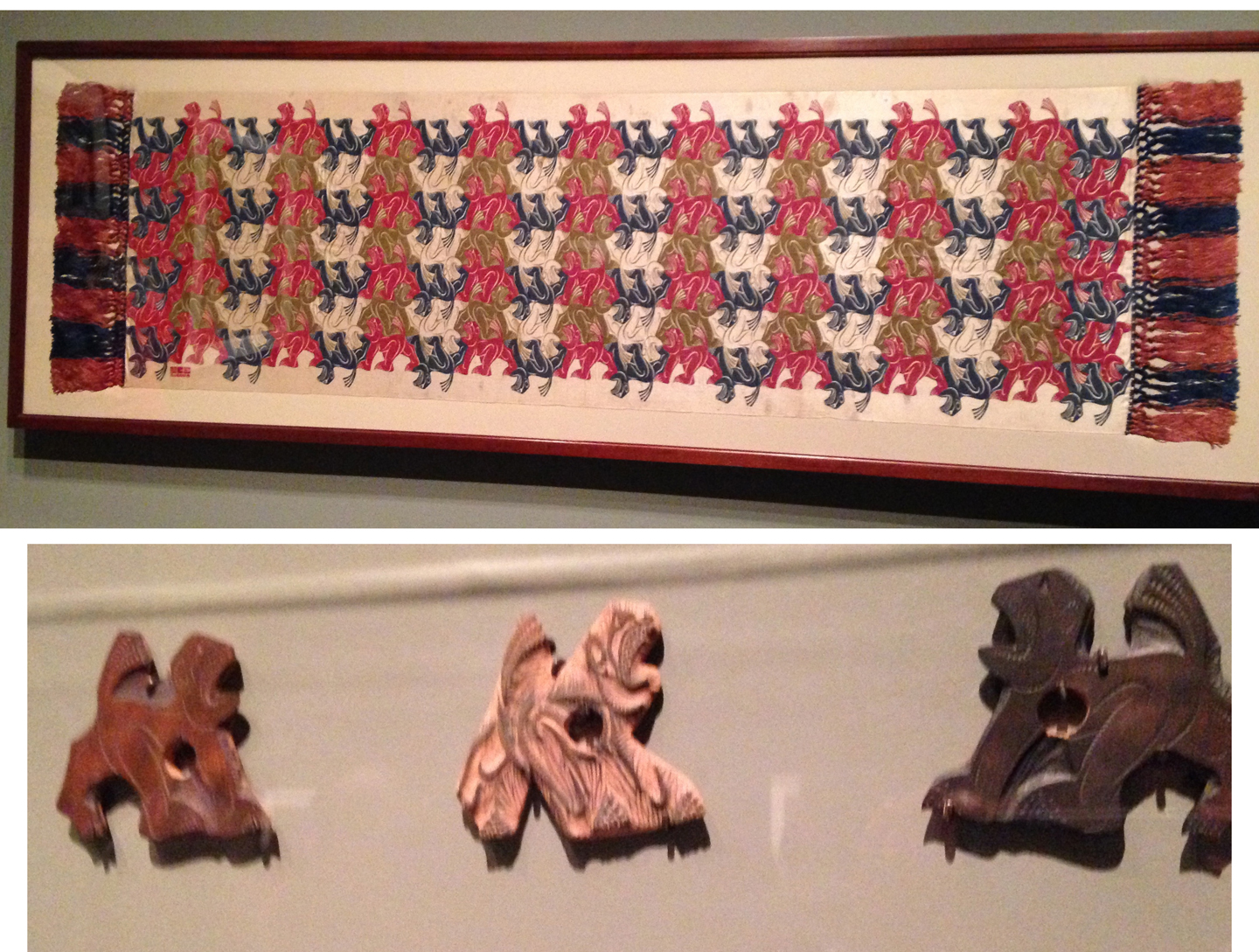

However, Escher was enthusiastic about the support of scientists and mathematicians, many of whom were the first to discover and purchase his work. Although he shunned Mick Jagger, Escher was thrilled that mathematician H. S. M. Coxeter asked to use one of his illustrations in an article, and this led Escher to create a new set of works on the theme of infinity, now called the Circle Limit series, shown in images from a recent exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of Art. Escher commented in a letter to his son afterward that the professor had sent him three pages explaining mathematically what he had drawn, and it was a pity he hadn’t understood a word of it.

© 2015 The M.C. Escher Company. Photo at left by Fenella Saunders, at right (4) by Jamie Vernon.

A mathematician also pointed Escher to the works of German mathematician August Ferdinand Möbius, and Escher later told his son that he had a Möbius strip inside himself just waiting to come out, which it did. That version, with marching ants on its surface (below), is now commonly used to teach the concept to students: If the strip were cut and laid flat, all the ants would be on the same side.

© 2015 The M.C. Escher Company. Photos by Fenella Saunders.

Although Escher had flunked calculus, curator David Steen of the North Carolina Museum of Art says it seems that Escher was one of those people who just instinctively understood the concepts. He had exposure to scientific thinking; his father was a civil engineer and his brother became a geologist; his eldest son became an engineer and his younger two sons also became geologists. Escher’s inherent spatial abilities shine through in his works, where he often worked from a sketch he made and transposed it backwards freehand onto a print plate. Steen explained that it was largely unknown that Escher would make up to 70 sketches before creating a final print, and would sometimes creatively combine sketches he had made many years apart into a final work.

© 2015 The M.C. Escher Company. Photos by Fenella Saunders.

The process of producing the artwork was also laborious. Escher’s famous tessellated scenes were often made using several print blocks, which he would ink and place by hand, using anywhere from 9 to 20 prints to make a single image. These hand-placed prints are perfect, with no misalignment or mistakes, which Steen says is a testament to Escher’s ability to visualize complex scenes.

© 2015 The M.C. Escher Company. Photos by Fenella Saunders.

Escher also had an interest in natural scenes, producing some incredibly detailed closeup illustrations of insects and flowers, for example. Those natural themes often pervaded his tessellated works. He would often do full-color paintings of tessellations as studies before producing a print that incorporated both tessellation and his other major theme of playing with perspective and reality, with subjects cycling between a drawn and a real state.

Escher lived during times of tumult. Steen believes he used art as a way to exert some kind of control on the chaotic world around him. To mathematicians, Escher’s precision brings life to abstract concepts, allowing them ways to better explain theories to their students. Escher stressed his affinity to science and math, even more than to art, and his meticulous process is reminiscent of an observational study. His need for control may have built his lasting aesthetic legacy, and will remain popular whether he would want it that way or not. However, one hopes that he would be pleased that his artwork might have had some role in pulling others into a fascination for math and science.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.