Finding Beauty in Microscopy

By Stacey Lutkoski

Biologists blur the line between art and science.

April 12, 2019

Science Culture Art Biology

Developments in microscopy have made it possible for biologists to witness cells and viruses operating in real time. An unexpected secondary benefit is that the resulting images can make for beautiful, museum-worthy pieces of art.

This past winter the University of North Carolina School of Medicine collaborated with the North Carolina Museum of Art to create the exhibit The Art of Science and Innovation (November 7, 2018–January 14, 2019). Fittingly located in the education wing of the museum, the technicolor images included detailed descriptions of how the researchers used advanced microscopy to scrutinize everything from molecules to cells to organs to organisms.

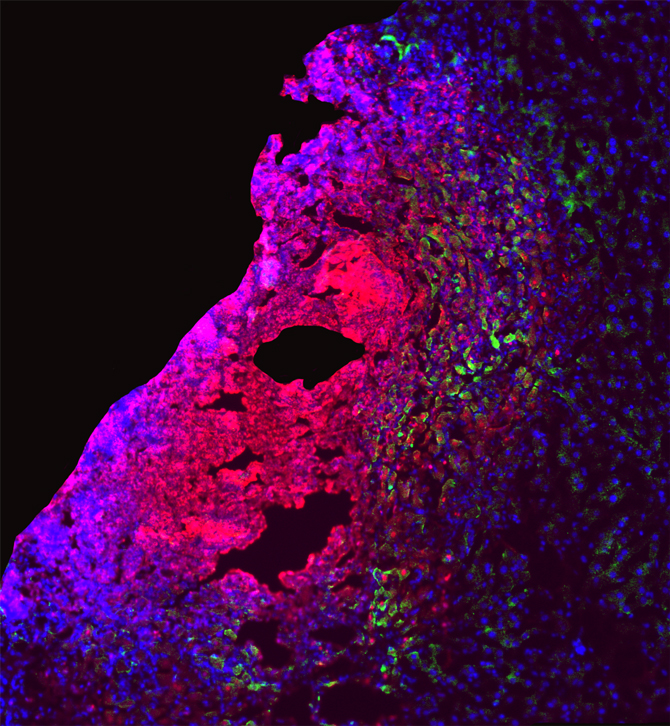

Microbiologists and immunologists Edward Miao and Vivien Maltez created the digitally tinted image Preventing the Purple Death (above) to illustrate the liver’s defenses against disease. In a liver lesion from a mouse infected with Chromobacterium violaceum, some cells are dying (red), while other, healthy cells (blue) are activating a protein (green) to fight the bacteria. The resulting image may lead to new treatments for preventing sepsis and liver abscesses in humans; it also creates a beautiful ombré effect, fading from red to blue, with spots of shocking green displaying the body’s defenses at work.

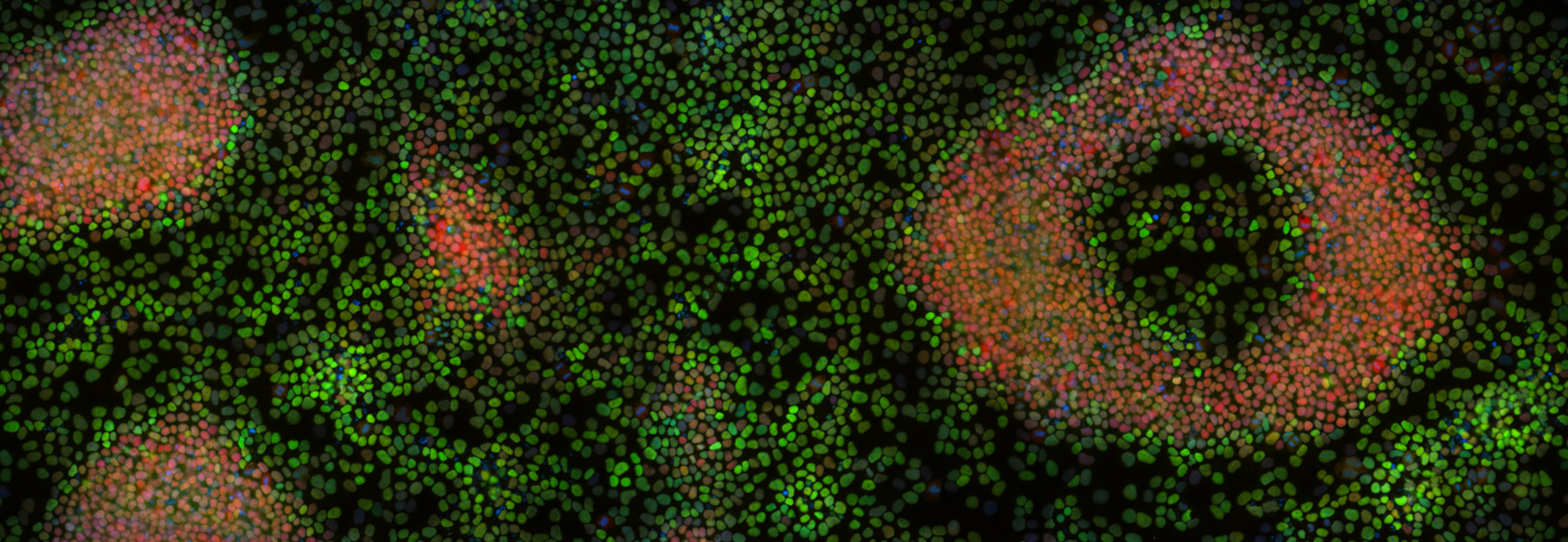

When cells are created, they have the potential to take on many different types of functions. Pharmacologist Jean Cook studies the process of how a cell determines what its future function should be, and how it transforms itself to fit that function. In An Eye on the Future (below), Cook shows the process at work: The green cells have committed to becoming muscles, while the red cells are still deciding what they want to be when they grow up. The image looks like abstract art, and it may help Cook’s team develop methods for repairing damaged tissue or halting the growth of cancerous cells.

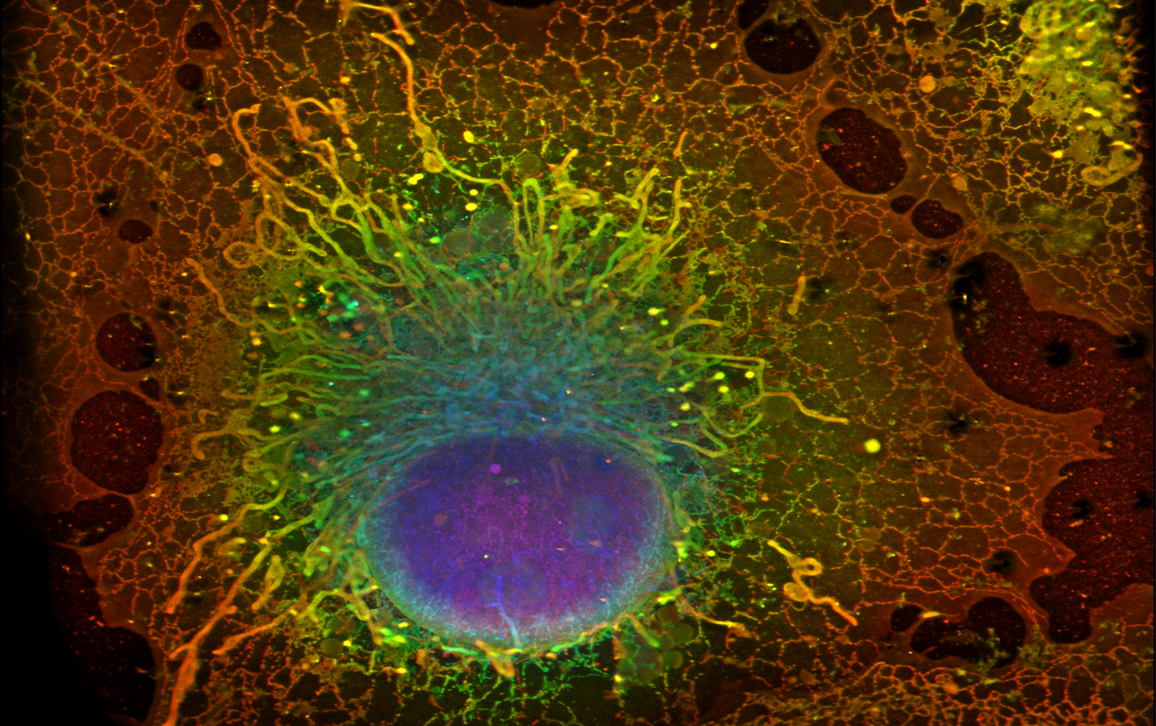

Before researchers can understand how cells operate, they need to know what makes up a cell. Biomedical engineer and pharmacologist Wesley R. Legant used super-resolution single-molecule localization microscopy, a process that magnifies and fluoresces individual molecules, to examine the inner workings of a cell. His image, titled Revealing Cellular Compartments (below), shows the organelles at work inside a cell. The cell’s DNA is encased in the purple and blue nuclear envelope. Fingers of yellow and green mitochondria (responsible for cell metabolism) reach out from the nucleus while the orange and red membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum synthesize proteins. The rainbow cell is shockingly beautiful; I plan to hang a poster-size print of it in my office.

All the images in the exhibit demonstrate the importance of visual representations to illuminating abstract or hypothetical processes. As microscopy techniques are further developed and refined, researchers will gain a better understanding of our bodies and our world. We can hope that they will share the images with us so that we can brighten our walls and enlighten our minds.

The image at the top of this blog post is another from the exhibit and was made by Mark Zylka, Bonnie Taylor-Blake, and Angie Mabb using confocal microscopy. They provided the following museum label:

The inhibitory neurons (green, magenta) are located in a brain region that plays a key role in learning and memory. Loss of neurons in this region contributes to Alzheimer’s disease, a brain disorder that initially impairs short term memory. We study how neurons in this and other brain regions—and the proteins that make the neurons function—contribute to conditions such as autism, Angelman syndrome, and Alzheimer’s.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.