The Choice of New Life: Musings from Antarctica

By Kristin Poinar

In The Quickening, Elizabeth Rush explores the melting of Thwaites Glacier and the decision to have a child in the face of the climate crisis.

October 19, 2023

Science Culture Environment Climatology Oceanography

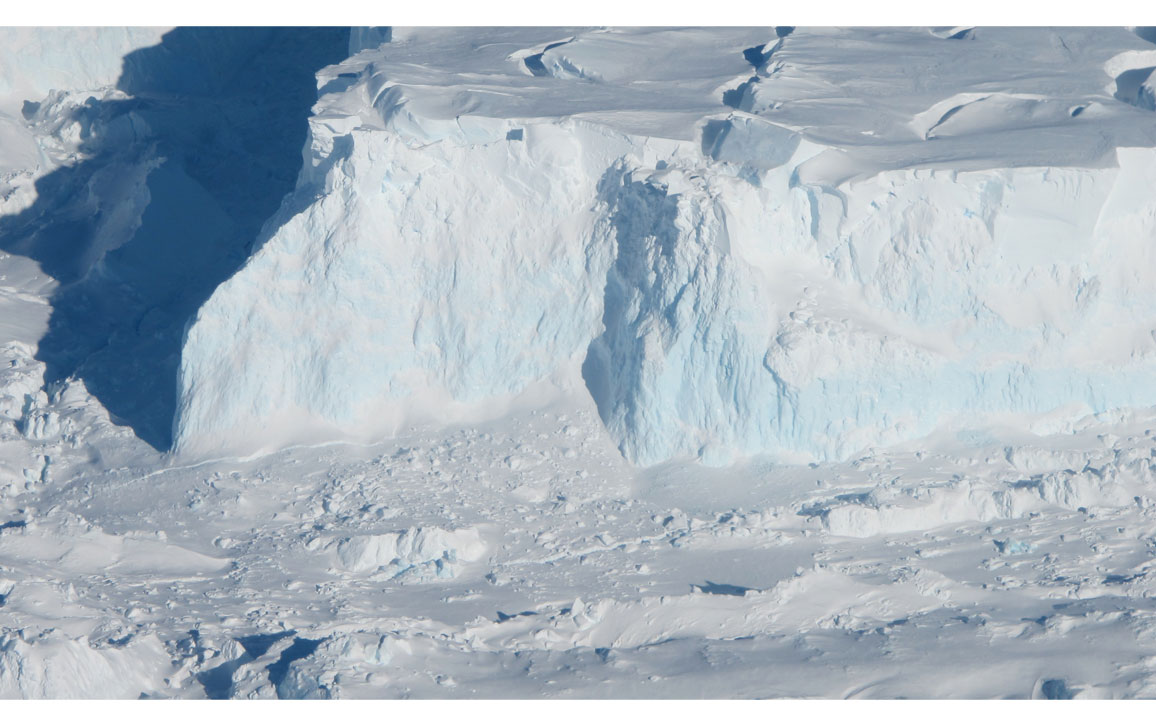

NASA/James Yungel

To pass medical clearance to go on a research trip to Antarctica, anyone with a uterus has to sign an affidavit not to get pregnant. It's a reasonable ask from a practical standpoint: Complications in early pregnancy can sometimes require serious medical treatment. Transport to a hospital from a research ship exploring iceberg-shedding glaciers at the ends of the Earth is far from guaranteed. Best, then, to not get pregnant in that environment.

"Why doesn't it say you're not allowed to make someone pregnant?" asks Anna Wåhlin, a scientist on board the Nathaniel B. Palmer for its 2019 expedition to Thwaites Glacier, Antarctica, as noted in Elizabeth Rush’s new book The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth.

Indeed, the latent misogyny.

Thwaites Glacier, a large and fast-flowing ice mass in Antarctica, threatens to collapse; if it does, it will drastically raise sea levels worldwide. The 2019 Palmer expedition carried three international teams of scientists to Thwaites Glacier to assess its past, present, and future stability. The expedition produced groundbreaking research findings; Rush observed the early phases of these discoveries on the expedition as part of the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

Rush is an English professor at Brown University in Rhode Island, a self-described New Englander with an implied greenness to the Antarctic terrain. In the decade leading up to this expedition, her interests in the natural world and science research mingled with her musings on climate change: Is it inevitable, or can human choices reverse it? Are Antarctic glaciers captives with a death sentence, or are they actors in some wider cosmic game? Is there truth in the classic Antarctic picture of danger and conquest, or is this the spin of the hundreds of masculine narrators? Pregnancy and birth were seemingly not initial points of focus for her mission; perhaps shifts in life goals that a few years can bring—or, more critically, having to sign the pregnancy affidavit at the age of 34—narrowed her thoughts to the major theme of the book: childbearing. "I'm hoping to have a family, but I had to postpone trying to get pregnant so I could come here," she says matter-of-factly to a few scientists over lunch in the mess hall one day. To the reader, though, she is less reticent about this. Rush sees pregnancy and birth everywhere: the protective belly of the ship, a glacier calving icebergs, and even her shipmates, from whom she solicits the stories of their own births.

Rush’s book gives highly detailed peeks into what goes on during an Antarctic research expedition. The ship's denizens hurry up and wait: a frenzy of planning and preparing, then jigsaw puzzles to while away the long hours of transit. One scientist confesses, "When I told my boyfriend what we've been doing every day, he said it sounds like we’re in an old people's home." The characters also ring true for a research expedition—the stoic lab manager wearing a "STEMINIST" t-shirt, or the crewwoman with a masculinized nickname who fearlessly pilots the Zodiac, decorates her hard hat with pink sparkles, and has never talked with her mother about her own birth. The book also succeeds at relating the daily science work and goals, including a trip to a raised beach to hunt for ancient organic matter that will be used to determine past sea levels, and round-the-clock shipboard lab sessions to process an ocean bottom sediment core. Rush is also honest in recounting her full impact on the science results: She includes the scene where she accidentally dumped one-third of an entire research project’s data onto the lab floor. The hot tears and cold guilt that settle in feel real.

When I was a much younger researcher—a shy graduate student similar to those found in these pages—I was myself part of an Antarctic research expedition, one member of an odd and very close community in 24/7 co-isolation. Rush’s depiction of the ship’s culture, born of the strict logistical conditions and forced socialization among exceptional strangers, is spot on, and a distinct strength of the book, along with the descriptive language about the environment. What is considerably weaker is the investigation of the “intimate question” advertised on the back cover: what it means to choose to have a baby in a world at the mercy of impending catastrophic climate change. I expected some heavy thinking, philosophy, or weighing of evidence surrounding this issue. By the time she boards the Palmer, though, Rush is enamored with fertility and pregnancy; she writes on the first page that this is the year that she decides to “try to grow a human being inside of my body.” When she does address the personal ethics of this choice, the treatment is cursory. The idea comes up repeatedly, but with a lack of depth. While Rush airs an intriguing and increasingly common concern about whether to have a child in a world locked into substantial climate change, she fails to add anything new to the popular conversation.

I read this book while conducting polar field work myself, in my baby’s first year of life. My own memories of the pre- and post-natal experience were fresh. I was eager for a reading journey into the wonders of pre-motherhood, when all is unknown and uncertain, and insights into the toll on our planet incurred by adding one more soul. In the slice of the Arctic where I am working, resident women have many babies. The social attitudes toward family building here could not be more different than in Rush’s Antarctica. Women push carriages along the streets every day, the babies inside bundled up against the chilly air and the relentless summer sun. Across the fjord from all of us, huge glaciers hold back an ice sheet while birthing icebergs into the sea. Our young ones do not know yet what they will inherit, but we know what we are giving them.

Rush writes a deeply human story that brings the research vessel to life. The Quickening will appeal to anyone interested in earth science, climate change, or exploration, and who has—or can at least try on—a feminist mindset for a journey to Thwaites Glacier, 75° south, mother of icebergs and catalyst for potential catastrophic sea level rise.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.