The Evolution of the 21st-Century Scientist

By Brian Kurilla

As more trained scientists leave traditional career paths, the distinction between scientist and nonscientist blurs.

August 12, 2016

Macroscope Communications

Throughout the past year, I've struggled with how best to define myself as a scientist. At times, I even questioned whether it's appropriate to refer to myself as a scientist.

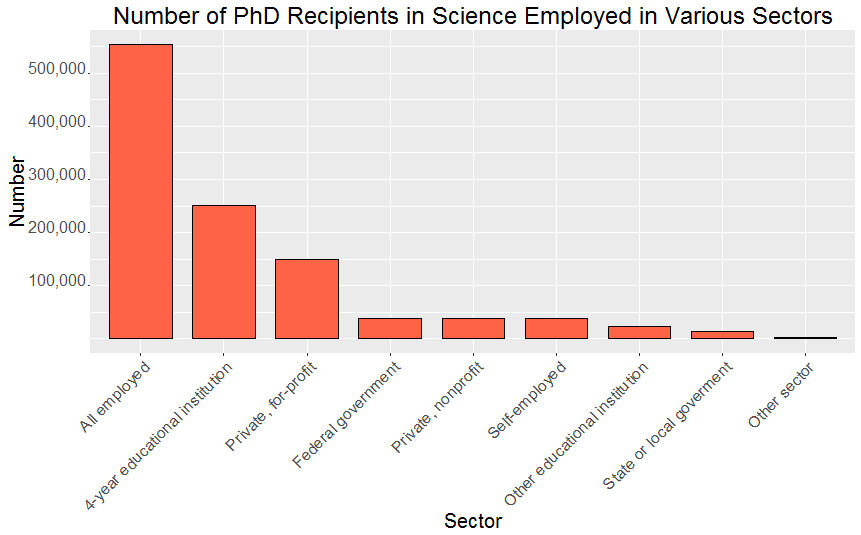

The thing is, even though I have a PhD in experimental psychology and multiple scientific publications to my name, I no longer work in a traditional scientific setting. That is to say, I don't teach or carry out my own research at a college or university, like many scientists. Indeed, according to a recent survey conducted by the National Science Foundation (NSF), roughly 45 percent of PhD recipients in science work at four-year educational institutions (see figure below).

Figure created by Brian Kurilla with data from the National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Doctorate Recipients, 2013. http://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/doctoratework/2013.

I freely chose to leave academia about a year and a half ago because, at the time, doing so was the best thing for my family. Nonetheless, the transition was difficult, especially after so much time devoted to preparation for what I thought would be my lifelong career—four years of undergraduate education followed by five years of graduate training and another two years of postdoctoral training.

After 18 months, I'm at last fully adjusted to life on the outside. But to get to this point, I’ve had to challenge my own heavily ingrained assumptions about what it means to be a scientist. For years, I had clung to the belief, likely held by so many others, that being a scientist necessarily means being an academic and a scholar. This view is wrong—more so now than ever—because the economic landscape for scientists is changing. As such, it might well be time for the entire scientific community to rethink what it means to be a scientist.

What Is a Scientist? A Generalist, Skills-Based Perspective

The word scientist is so commonplace in our society that many of us share the same generic idea of what it means to hold this title. For instance, when asked to think of a scientist, many people probably picture white lab coats, glass beakers, test tubes, and laboratories full of sophisticated equipment.

Many also probably think of scientists as experts on a particular topic or issue, such as human evolution, climate change, the nature of the cosmos, or the underlying forces that shape human behavior. But deep knowledge about a particular subject area is not what makes someone a scientist, even if this is a defining characteristic of an academic or scholar.

Science is about far more than the accumulation of facts. It’s about the process we use to acquire knowledge. Facts can change over time with subsequent research and discovery, but what doesn't change over time is the method and approach used by scientists to study the natural world. As Michael Shermer, founding publisher of Skeptic magazine, likes to say: "Science is not a thing. It’s a verb."

Because science is a path to knowledge, rather than knowledge itself, I prefer to take a generalist approach to how I define the term scientist. To me, a scientist is not merely a lecturer or a scholar or an expert in a particular collection of facts. Rather, a scientist is an expert in all of the broad and highly transferable skills comprising the scientific method—skills such as logical reasoning, critical thinking, creative thinking, observation, organization, data collection, data analysis, mathematics, and writing, to name a few.

It’s crucial for future generations of scientists to recognize the importance of transferable scientific skills over scientific knowledge because, nowadays in many fields, landing a good job in traditional academic research is neither guaranteed, nor even altogether probable. As such, the average scientist of tomorrow may find herself employed in a setting very different from that of the average scientist of today.

A Changing Landscape for Scientists in the 21st Century

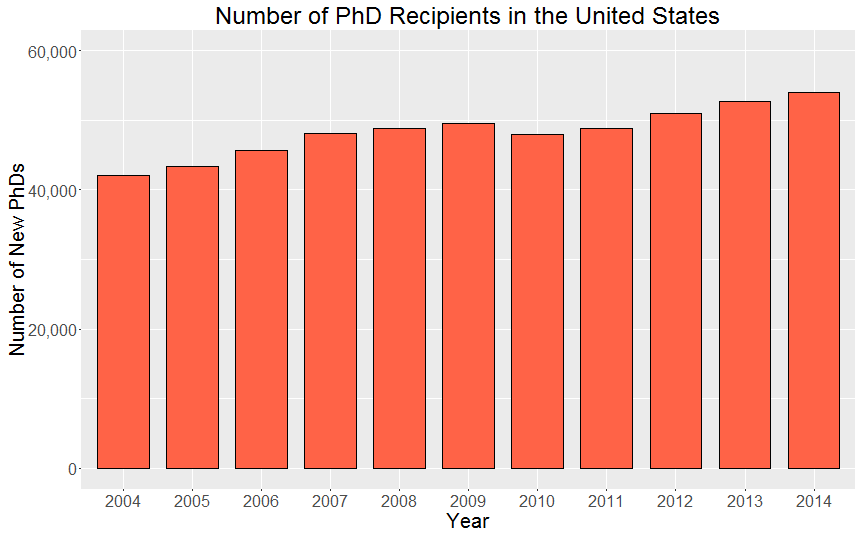

If you pay attention to news in academia and higher education, then you've likely seen stories about how the academic job market for recent PhD graduates is exceedingly tight these days. Each year, the number of PhD recipients that graduate from U.S. colleges and universities grows. Furthermore, each year the number of new PhD graduates far surpasses the number of academic jobs that are available. It’s been estimated that in some fields, such as biomedical research, the chance of landing a tenure-track faculty position is as low as 13 percent.

Figure created by Brian Kurilla with data from the National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2015. Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2014. Special Report NSF 16-300. Arlington, VA. Available at http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2016/nsf16300/.

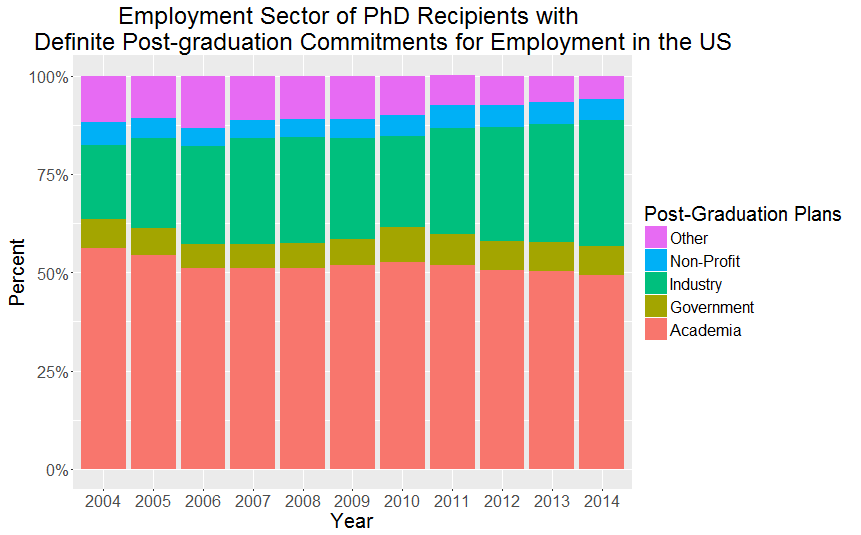

Not surprisingly then, many scientists have begun to move away from the traditional academic career path. According to the NSF, there has been a steady decline over the past decade in the percentage of PhD graduates with definite plans to work in academia, from 56.1 percent in 2004 to 49.3 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, over the same period of time, the percentage of PhD graduates with definite plans to work in business and industry rose considerably, from 19 percent in 2004 to 32 percent in 2014 (see the chart below). These percentages are based on the number of PhD recipients who report having a definite commitment for employment upon graduation. Worryingly, the percentage with no definite commitment for employment or postdoctoral study also rose from 2004 (30 percent) to 2014 (39 percent).

Figure created by Brian Kurilla with data from the National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2015. Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2014. Special Report NSF 16-300. Arlington, VA. Available at http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2016/nsf16300/.

If these trends signal a broad and sustained shift in employment prospects for scientists, then it’s possible that business and industry might displace academia one day as the primary career path in science. Of course, this outcome is neither good nor bad on its own. However, there is a perception among some in the business world that recent PhD graduates are generally unprepared for careers outside academia.

So, as the need for skilled scientists and data analysts continues to grow among various business sectors and industries—and as the academic job market continues its present slump—scientists will need to work hard to diversify their skill sets to achieve broader appeal on the job market. For example, they could learn a computer programming language, improve their skill writing for a general audience, or practice effective interviewing and networking strategies.

Pursuing a career outside academia will also mean adopting a generalist view of the term scientist. Scientists are not necessarily experts in facts, but rather experts in all the skills of the scientific method. From this perspective, it’s clear that scientists are well suited to a host of careers outside academia—from research analysts at businesses and universities, to data scientists, user experience researchers, technical writers, and virtually any other type of position that calls for intellectual curiosity and careful attention to precision and accuracy.

Undoubtedly, scientists face serious challenges in the 21st Century. And some of these challenges may even come to reshape the professional role of scientists, from traditional academic and scholar to something more along the lines of business professional. But I choose to be optimistic and believe the changing economic landscape will ultimately prove to be a good thing for science and society.

Just as scientists throughout history have rarely limited the scope of their curiosity and ambitions to explore and understand the natural world, so too should aspiring scientists make sure never to limit unnecessarily and prematurely the scope of their own professional ambitions. After all, a fulfilling career in science can most certainly be found outside academia. And when scientists work outside traditional boundaries, this just means more people and organizations can benefit from our talents and insatiable curiosity about the natural world.

What does being a scientist mean to you? How important is it to you that a scientist works in an academic setting? And what can universities, as well as student researchers themselves, do to prepare future generations of scientists for nonacademic careers?

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.