COVID-19 Reveals a Path Forward on Climate Change

By Richardson Dilworth, Scott Gabriel Knowles, Franco Montalto, Mimi Sheller

The scale of societal cooperation, compliance, and inequality during the pandemic holds lessons for those seeking meaningful climate action.

May 12, 2020

Macroscope Environment Policy Climatology Human Ecology

Four months after the disappointment of the most recent United Nations climate conference (COP25)—at which no new rules creating a global carbon market were reached, no new mechanisms for compensating developing countries harmed by climate change were established, and no formal statement expressing the need for more ambition in efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions was articulated—human activity has shifted drastically. As we write, there are 4.2 million confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), more than a quarter-million deaths, roughly 2.5 billion people staying at home, and millions unemployed, all while the global economy is effectively shut down.

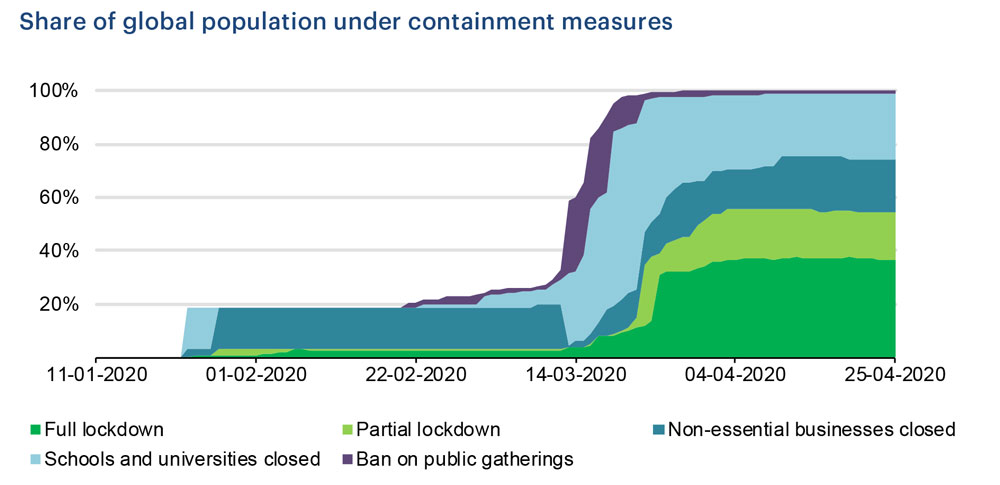

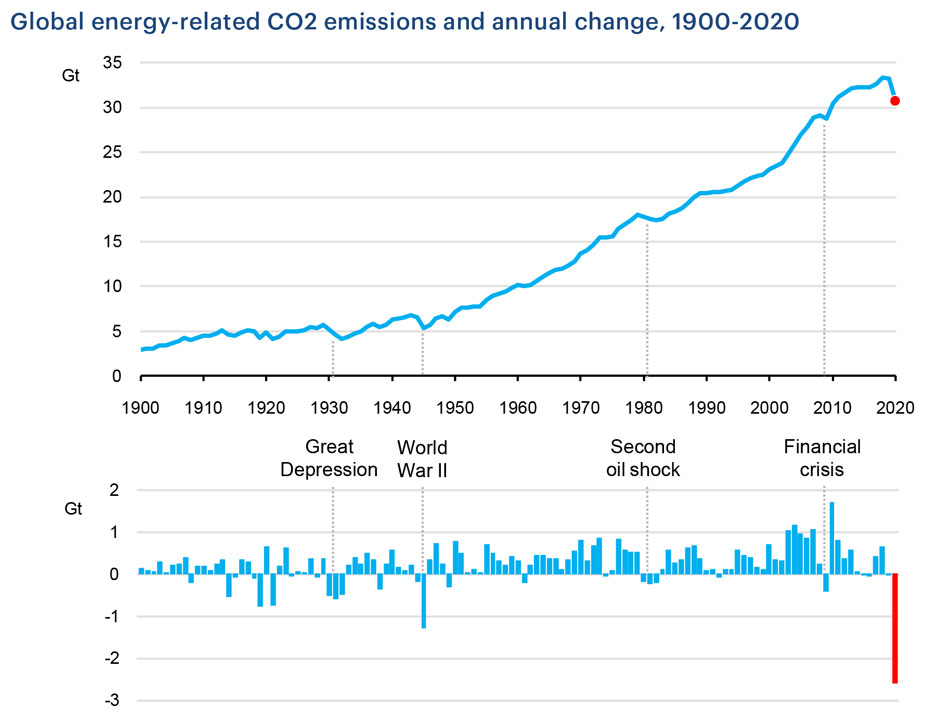

It is perhaps no surprise that such changes in the behavior of human beings, labeled a hyperkeystone species by biologists Boris Worm and Robert Paine, would be detectable in the natural world. Enforced human immobility and the shutdown of carbon intensive industrial operations have silenced human noise and improved air quality; emboldened wildlife to openly roam cities and giant pandas to mate in shuttered zoos; and, after setting new highs in each of the past two years, greenhouse gas emissions are now projected by the International Energy Agency (IEA) to drop by 8 percent this year.

“Violent economic and social upheaval are not prerequisites for the mitigation of climate change.”

Even though these outcomes show nature’s resilience, they are accompanied by the loss of many human lives. Violent economic and social upheaval are not prerequisites for the mitigation of climate change. Rather, our work on sustainability and climate change is motivated by a desire to improve the human condition through the design of a carbon-neutral circular economy that simultaneously builds economic, natural, and social capital. We do not want to confuse the consequences of a temporary pause in consumer economies with the structural changes needed to avoid the most devastating effects of climate change. That goal requires a similar reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (about 7.6 percent) every year between 2020 and 2030, and that reduction must be accompanied by equally ambitious efforts to promote social justice and equity. UN Secretary General António Guterres could have been discussing COVID-19 when he pointed out that solutions to the climate crisis that do not benefit everybody will lead to the “survival of the richest.”

What do the voices speaking in this frightening moment tell us about how we need to structure sustainable climate action? Like those in climate denial, individuals concerned principally with the pandemic’s effects on the economy and personal liberties are rushing to suspend life-saving measures (sheltering at home) in favor of “business as usual.” Their emphasis is on the economic “restart,” with suspended environmental regulations and subsidies for fossil fuels. This carbon-committed approach leads directly to the stubborn status quo that would not budge at COP25.

“Billions around the world have accepted an abrupt and radical change to their lives, virtually overnight and amid profound uncertainty.”

But billions around the world have also accepted an abrupt and radical change to their lives, virtually overnight and amid profound uncertainty, all to slow the spread of the virus. Social science research proves time and again that disasters reveal the human capacity for creativity, improvisation and community formation, and helping others (even strangers) survive, and COVID-19 is no exception. These collective responses to COVID-19 prove that even in today’s complex world we do not need to wait for mitigation and adaptation behavior to emerge. The pandemic shows us that when scientific authorities such as Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, prescribed drastic social distancing to allay COVID-19 effects, people responded—despite hyperpartisanship and often in defiance of science skeptics.

Figure courtesy of the International Energy Agency.

The agility and speed with which such life-saving policies took hold provide many rich and transferable lessons to the climate crisis, from how science is effectively communicated to the public, to the psychological frames needed to maintain alarm, build social commitment, and drive policy momentum. However, it is also true that this kind of prosocial behavior after disasters is not applied uniformly; it is constrained by factors of time, ideology, geography, and social difference. Social inequities, in particular, represent a severe handicap in our efforts to adapt the human condition for the better, whether fighting a pandemic or mitigating climate change.

“Social inequities represent a severe handicap in our efforts to adapt the human condition for the better, whether fighting a pandemic or mitigating climate change.”

Overwhelming evidence now indicates that racial and ethnic minority populations are shouldering a disproportionate burden of illness and death, especially people working in risky, low-wage, high-stress jobs, whether within the United States or in other countries. When we sacrifice the essential workers in our fields, factories, warehouses, meat-processing plants, and grocery stores, and fail to support the teachers, nurses, health aids, cleaners, and drivers who take care of us all, we deepen human suffering. Such exploitation of vulnerable people often parallels the over-exploitation of natural resources associated with “sacrifice zones” of toxic pollution and ecocide. The outlook for the world’s poorest countries to recover from the pandemic’s economic shock, as well as their outlook as the climate changes, is dim without a massive outpouring of international aid—or without “climate reparations” to make up for the carbon debt of large-scale emissions by wealthier countries and major carbon-emitting companies.

Figure courtesy of the International Energy Agency.

How can we convert the best aspects of our current COVID-19 disaster response into more long-lasting and thoroughly equitable collaboration to stop climate disasters? First and foremost, we need to decrease the inequities that will only grow more brittle as the climate continues to change. Making improvements to supply chains, improving the global availability of medical supplies, or implementing disaster forecasting and early warning systems will help us survive climate change as much as pandemics; so too will international accords to protect migrants, support displaced workers, and help communities facing “slow disasters”—of which poverty itself is the slowest of all.

COVID-19 has exposed and will exacerbate inequalities, but our responses to it also will point to new questions and solutions. What government policies will be most helpful in keeping greenhouse gas emissions low as the economy opens up? German chancellor Angela Merkel, for example, has led calls for a “green recovery” as part of the European response to the global health crisis; advisors to the United Kingdom government have made essentially the same recommendation. The IEA has speculated that the pandemic may permanently reduce markets for most fossil fuels while increasing the economic viability of renewables. Cities such as Paris and Milan are increasing space for pedestrians and bikes, banning cars, and installing express bus lanes while traffic is light. The Pakistani government is employing tens of thousands of idle workers in planting billions of trees to reduce climate risks. Companies allowing employees to work more from home may reduce commuter traffic and the need for office space, lowering greenhouse gas emissions. And individuals are shifting their patterns of consumption and experimenting with new lower-carbon lifestyles. In Philadelphia, we are attempting to alleviate COVID-19’s economic stress by employing civic scientists in a National Science Foundation–funded study to better understand the role of park usage in the era of social distancing.

Yet without formalizing and expanding such innovations throughout the economy, the pandemic could easily trigger behavior that makes it harder to achieve our climate change goals. With local and regional mass transit systems in fiscal crises from which they may never recover, people might turn to less energy efficient ride-sharing services or worse, increase private automobile trips. We already see car traffic and air pollution rapidly rising in Chinese cities, while refineries ramp up production. Reliance on home deliveries was already growing and is now accelerating Amazon’s market dominance and the demise of local shops in dense walkable neighborhoods. Government subsidies to save airlines, car manufacturers, and fossil fuel industries may entrench climate-harming patterns of mobility rather than pushing forward low-carbon transitions.

Unless we intentionally redesign the obdurate systems that have disproportionately elevated risks for a large and vulnerable segment of the global population, the effectiveness of our solutions to existential crises will remain uneven and unacceptable. Many leaders now recognize, as noted in a Center for Urban Studies webinar, that we need strategies, policies, and investments to reignite our economy, restore critical industries, put people back to work, “ensure that the recovery is inclusive” and “strengthen parts of the economy that may prove resilient to future challenges.”

At a minimum, the global response to COVID-19 should not exacerbate the risks of climate change. Something else is possible: The collective actions that are saving lives in the pandemic point the way toward a more sustainable climate future.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.