How to Detect Faked Photos

By Hany Farid

Techniques that analyze the consistency of elements within an image can help to determine whether it is real or manipulated.

Techniques that analyze the consistency of elements within an image can help to determine whether it is real or manipulated.

“Photographers, especially amateur photographers, will tell you that the camera cannot lie. This only proves that photographers, especially amateur photographers, can, for the dry plate can fib as badly as the canvas on occasion.”

—The Evening News,

Lincoln, Nebraska, November 1895

It may be an old adage that “the camera cannot lie,” but as the above quotation demonstrates, even when photography was young in the late 1800s, it was widely acknowledged that an unusual play of the light or a glitch in the equipment could cause accidental or purposeful trick images, such as ghostly apparitions. In a July 1874 article in The Photographic Times, photographers are warned that inconsistent shrinkage in photographic negatives or printing paper could cause distortions in photographs recording the transit of Venus that year, among other subjects.

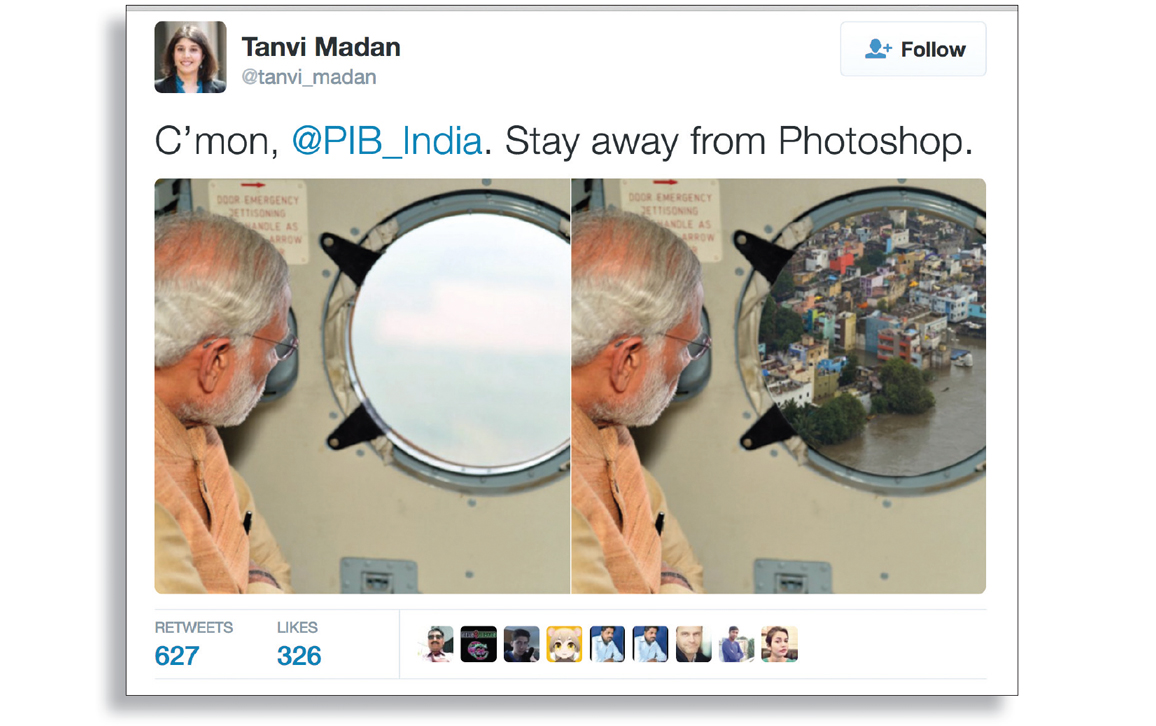

Image courtesy of Tanvi Madan.

But clever camera tricks pale in comparison with the possibilities now available for manipulating images. With startlingly fast advances in digital technology, it has become increasingly difficult to distinguish actual photographs from ones that have been digitally distorted or were created wholly by a computer. Such doctored photographs have appeared in tabloid and fashion magazines, and on online auction and dating sites, but also in mainstream and government media and in political ad campaigns. For instance, in 2015 the Press Information Bureau of the Government of India released a photograph of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi surveying by air the flood damage in the city of Chennai. The image of the flooded city, however, had been superimposed in the window of Modi’s plane, and the manipulation received a great deal of ridicule in the press and on social media.

Even most scientific journals have found the need to implement a policy that distinguishes between what might be acceptable digital “cleaning up” of an image and what ventures into falsifying data. For instance, the Journal of Cell Biology gives an example in which scientists increased the contrast of only certain elements in a micrograph, and also removed some background distractions, to the point that their actions were deemed to be misconduct.

The field of photo forensics has emerged to restore some trust in photographs. These forensic techniques begin by modeling the entire imaging pipeline from the physics and geometry of the interaction of light, to the interaction of the light as it passes through a camera lens, the conversion of light to pixel values in the electronic sensor, the packaging of these pixel values into a digital image file, and the pixel-level artifacts introduced by photo-editing software such as Photoshop. From within this large body of forensic techniques, I will describe three geometric techniques for detecting traces of digital manipulation.

You have almost certainly seen a photograph of train tracks receding away from you in which the gap between the tracks appears to shrink. In the actual three-dimensional scene, the gap between the tracks is, of course, fixed, but it appears to shrink because of the basic properties of perspective projection, in which the size of an objected imaged onto the camera sensor (or your eye) is inversely proportional to its distance from the camera. If the train tracks had infinite length, then they would converge in the image to a single point—the vanishing point.

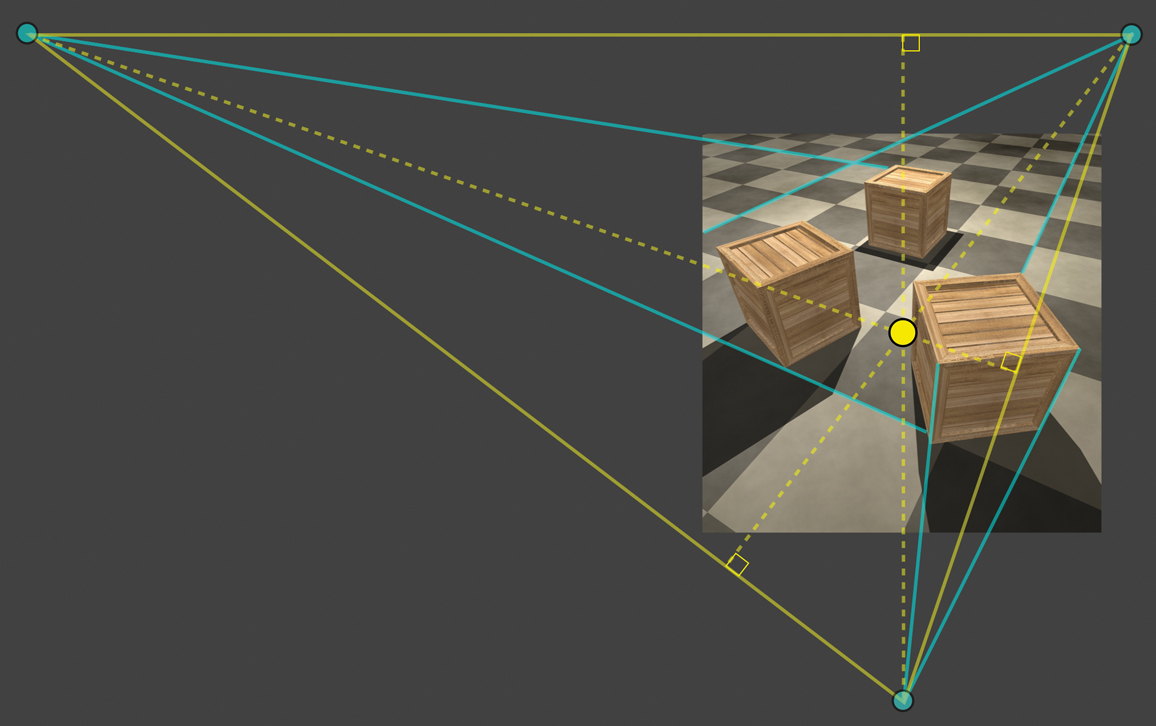

Image courtesy of Hany Farid.

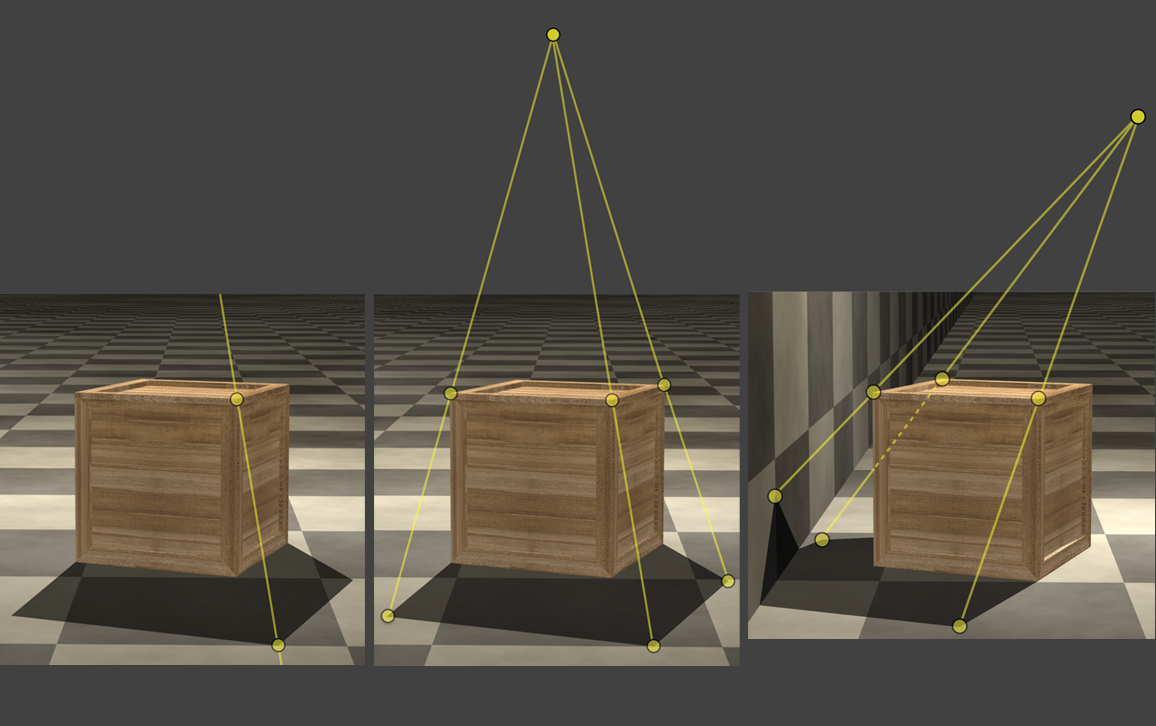

The location of a vanishing point in the two-dimensional image depends on the orientation of the parallel lines in the 3D scene. Shown in the figure above are three different vanishing points (shown in cyan) computed from the horizontal and vertical lines between the tiles and from the sides of one of the boxes. These three vanishing points correspond to three pairs of lines that are mutually perpendicular in the 3D scene. Because of this special relationship, these three vanishing points provide useful forensic information (vanishing points have several other interesting and useful geometric properties that we don’t have room to discuss here).

If lines connecting corresponding points in a scene and its reflection do not converge on a common intersection in the image plane, the image may be a fake.

The principal point of an image corresponds to the intersection of the camera’s optical axis and sensor. It is possible to recover the principal point by first identifying three mutually perpendicular sets of parallel lines in the scene. Each set of parallel lines has a vanishing point, and together the three vanishing points form a triangle. For each of the three sides of a triangle (solid yellow line in the figure above), there is one line, the altitude (dashed yellow line), which extends perpendicularly from that side to the opposing vertex of the triangle. The three altitudes of a triangle intersect at a point called the orthocenter (yellow dot). The orthocenter is the camera’s principal point.

An image has only one principal point, typically at or near the image center. In the example above, the principal point is near the image center, as would be expected in an authentic image. If the principal point deviates significantly from the image center, then we would have cause to question the authenticity of the photo (assuming, of course, that the image has not been cropped from its original recording).

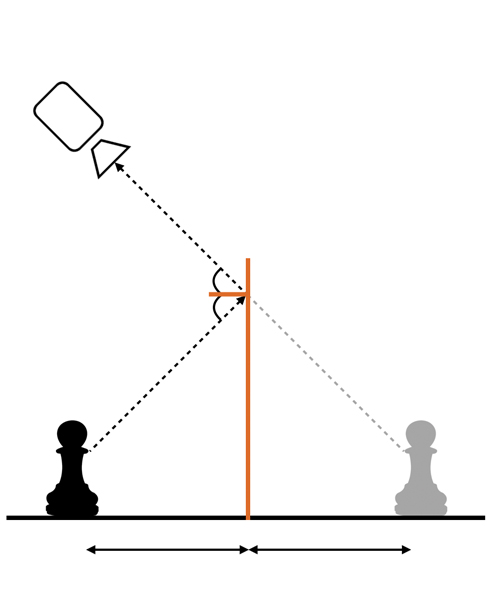

With a perfect mirror (orange), light rays are reflected in a single direction, creating an image in which a black chess pawn and its reflection (gray) are equal in size and in distance from the mirror. If this geometric relationship between objects in an image is not correct, tampering may be the cause.

Image courtesy of Hany Farid.

The schematic on the right shows the relationship between a camera, a mirror (orange), an object (a black pawn), and the pawn’s reflection (gray). A perfect mirror reflects light rays in a single direction. A light ray from a point on the pawn is reflected by the mirror to a single point on the camera sensor, and, at the sensor, these reflected rays are indistinguishable from light rays originating from a pawn located behind the mirror. This virtual pawn and the real pawn are exact mirror images: They are equal in size and equal in distance from the mirror. This basic geometry holds for the reflections of any flat specular surface such as a mirror, window, or even a highly polished tabletop. At first glance there seems to be little relationship between reflections and vanishing points, but a similar analysis can be used to determine whether objects and their reflections have the correct geometric relationship.

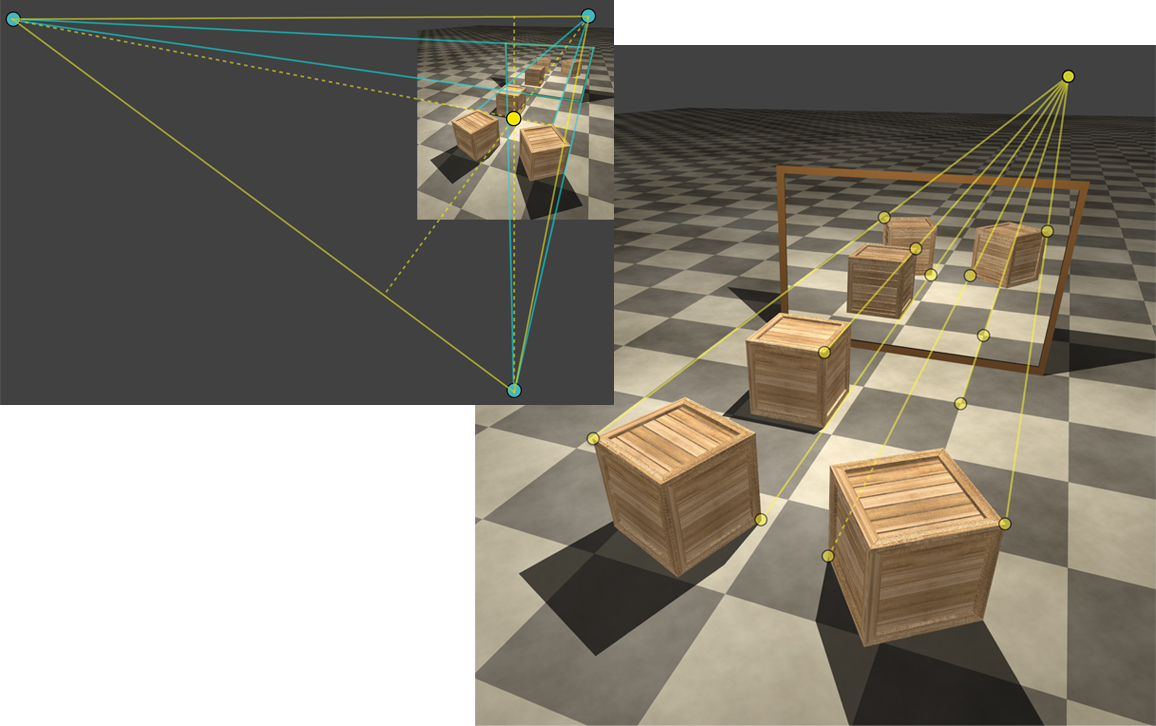

Images courtesy of Hany Farid.

Consider the scene in the figure above in which three boxes are reflected in a flat mirror. The yellow lines connect corresponding points on the real and virtual boxes. In the 3D scene, these lines are parallel to each other and perpendicular to the mirror. In the 2D image, however, due to perspective projection, these parallel lines converge to a single point, just as parallel lines in any 3D scene converge to a vanishing point. Because the lines connecting corresponding points in a scene and its reflection are always parallel, these lines should have a common intersection in the image plane. If one or more of the lines do not converge on this common intersection, then the image may be a fake.

Reflections may also provide additional forensic evidence. Recall that it is possible to recover the principal point from three mutually perpendicular sets of parallel lines in the scene. If the scene contains a rectangular reflective surface, such a rectangular mirror, then the edges of the mirror provide two mutually perpendicular sets of parallel lines. Because the rays connecting an object to its reflection are perpendicular to the mirror surface, these rays provide the third, mutually perpendicular set of parallel lines. A reflection in a rectangular reflective surface can be used to verify the position and uniqueness of the principal point. The result of this calculation can be cross-checked against the principal point estimated directly from three vanishing points.

In general, a shadow’s location provides information about the location of the surrounding light in the scene. We expect that these lighting properties will be physically plausible and consistent throughout the scene. Thus an object’s cast shadow can be used to constrain and reason about the location of the illuminating light source.

Let’s start with a simple situation: a scene illuminated by a single small light source. Consider the 3D scene depicted below in which the box is casting a shadow on the floor. For every point in this shadow, there must be a ray to the light source that passes through the box: The box is occluding the floor from direct illumination by the light. For every point outside of the shadow, there must be a ray to the light source that is unobstructed by the box: The floor is directly illuminated by the light. Consider now a ray connecting the point at the corner of the shadow and its corresponding point at the corner of the object. Follow this ray and it will intersect the light.

Images courtesy of Hany Farid.

Because straight lines are imaged as straight lines (assuming no lens distortion), the location constraint in the 3D scene also holds in a 2D image of the scene. So, just as the shadow corner, the corresponding box corner, and the light source are all constrained to lie on a single 3D ray in the real world; the image of the shadow corner, the image of the box corner, and the image of the light source are all constrained to lie on a single 2D ray in the image.

Now let’s connect two more points on the cast shadow to their corresponding points on the object (above, middle). We will continue to use the corners of the box because they are particularly distinct. These three rays intersect at a single point above the box. This intersection is, of course, the projection of the light source in the image.

The light source is often not visible in the original image of the scene. Depending on where the light is, you may have to extend the rays beyond the image’s left, right, top, or even bottom boundary to see the intersection of the three rays. For now, we will continue to examine the case in which the light source is above and in front of the camera.

The geometric constraint relating the shadow, the object, and the light holds whether the light source is nearby (such as a desk lamp) or distant (the Sun). This constraint also holds regardless of the location and orientation of the surfaces onto which the shadow is cast. Consider a shadow that falls on two surfaces (above, on right). Every ray connecting a point on the cast shadow to its corresponding point on the object must intersect the light. Where the shadow is cast is irrelevant. All of the rays, regardless of the scene geometry, will therefore intersect at the same point.

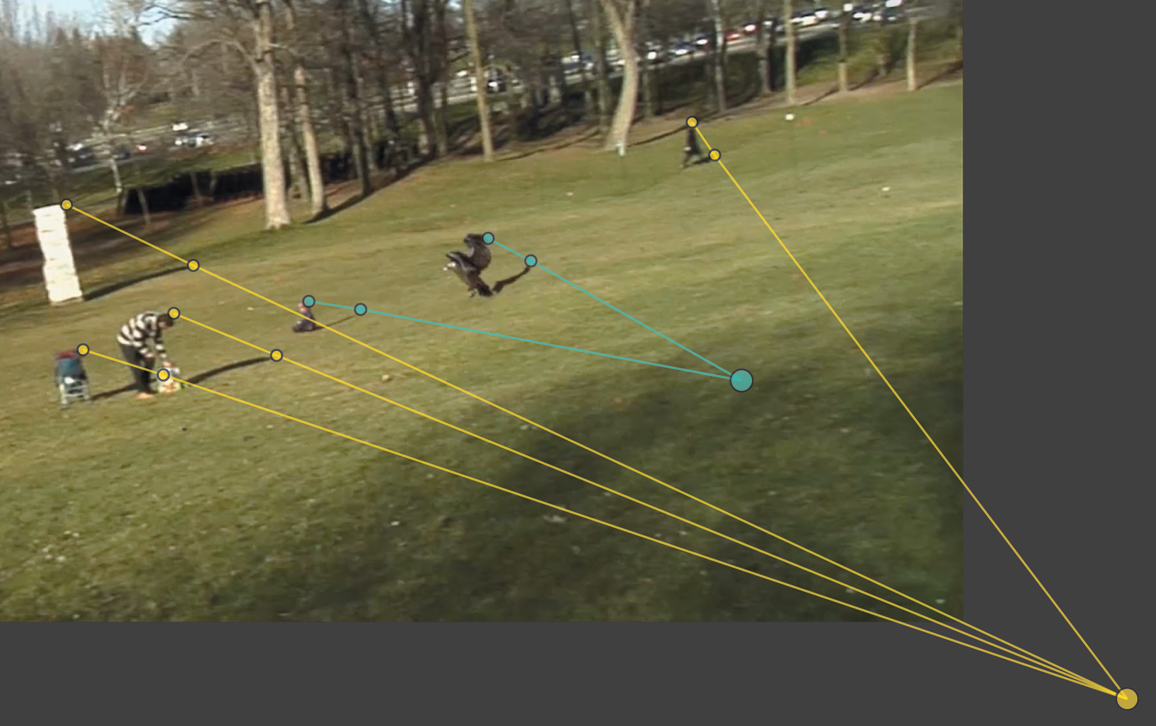

One of the most watched YouTube videos of 2012 starts with a panning shot of an eagle soaring through the sky. The eagle makes a slow turn and then quickly descends upon a small child sitting on a park lawn. The child’s parent is nearby but looking the other way. The eagle snatches the child. As the eagle starts to ascend, it loses its grip and the child drops a short distance to the ground. At this point, the videographer and parent run to the seemingly unharmed child. This video, titled “Golden Eagle Snatches Kid,” quickly garnered tens of millions of hits by viewers, who responded with a mixture of awe and skepticism. Although this was a clever and well-executed fake, a shadow analysis shown at right reveals that the shadows of the baby and eagle (cyan lines) are inconsistent with the rest of the scene (yellow lines). Indeed, this video is a composite of a computer-generated baby and eagle added into an otherwise real video.

Image courtesy of Robin Tremblay, NAD School of Digital Arts, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi.

It can be difficult to reason about the 2D location of shadows that results from the 3D interaction of geometry and lighting. And our visual system is often completely oblivious to glaring inconsistencies in shadows. This simple shadow analysis, therefore, can be highly effective at detecting inconsistencies in lighting and shadows that may result from photocompositing.

Straight lines (real or virtual) in a 3D scene become straight lines in its 2D image. This simple fact of perspective projection yields a common geometric principle for analyzing vanishing points, reflections, and shadows.

All of the light rays, regardless of the scene geometry, should intersect at the same point, whether the light source is nearby or distant.

But the accuracy of each of these analyses rests on the accuracy of the selected lines. For the vanishing point analysis, it is essential to specify clearly defined straight lines. For the reflection and shadow analyses, it is essential to use distinctive points so that the specified lines are unambiguous. If care is not taken, even slight errors in the specification of these points and lines can lead to erroneous conclusions. These analyses also assume that straight lines in the scene project to straight lines in the image. This assumption may not hold for inexpensive cameras, which can introduce geometric distortions that cause straight lines to project to curved lines.

The three geometric forensic techniques described here are only a small set of a large and diverse toolkit of forensic techniques that are available to a forensic examiner. Other forensic techniques include the analysis of specular highlights, lens distortion, lens flare, color filter array interpolation artifacts, sensor noise, artifacts in the compression of digital imaging formats such as JPEG, and more. But with an understanding of some of the basics, viewers can be better equipped to make an informed decision about whether the images they are looking at are genuine or compromised.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.