This Article From Issue

July-August 2005

Volume 93, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/2005.54.0

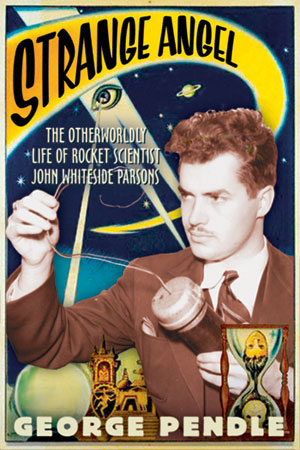

Strange Angel: The Otherwordly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons. George Pendle. xii + 350 pp. Harcourt, 2005. $25.

Astro Turf: The Private Life of Rocket Science. M. G. Lord. xii + 259 pp. Walker and Company, 2005. $24.

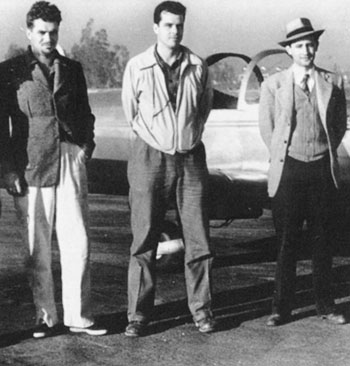

In 1935, three California experimenters—John Whiteside ("Jack") Parsons, Edward Forman and Frank Malina—got together to develop and test rocket engines. Parsons and Forman were barely more than enthusiastic kids fresh out of high school, and Malina was a 22-year-old graduate student at Caltech. They would go on to become founders of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the Aerojet Engineering Corporation. The fascinating story of this trio and the early days of American rocketry research can be found in two new books, Strange Angel, by George Pendle, and Astro Turf, by M. G. Lord.

Parsons, Forman and Malina had diverse backgrounds and interests, but their skills were perfectly complementary. Parsons, the group's chemist, grew up on Millionaire's Row in Pasadena, scion of a rich family from back East, but his family lost their money during the early years of the Depression, so he was unable to afford college. He had enthusiasm for a hundred different subjects: poetry, fencing, classical music, the occult, explosives and, above all, rockets. Most of his knowledge of chemistry was self-taught or learned on the job at an explosives manufacturing plant.

Forman, who had been Parson's best friend since high school, was the machinist of the group—a skill that would prove critical for their endeavors. According to Lord, he "could cobble together almost any device out of junkyard finds." Looking back on their early efforts, Forman later said that "It was our desire and intent to develop the ability to rocket to the moon." In the 1930s, that was an ambitious goal indeed.

Malina, the group's theoretician and mathematician, was the son of Czech dissidents who had come to America to escape repression. He had studied mechanical engineering as an undergraduate, but he was also a musician and an artist. As a graduate student, he convinced aerodynamicist Theodore von Kármán to approve a thesis in rocket design at the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratories of the California Institute of Technology (GALCIT). Parsons and Forman met Malina when they were drawn to the Caltech campus by a newspaper article about a lecture on rocket technology, and through him they gained access to Caltech's resources.

Strange Angel focuses on Parsons, who was certainly the craziest and arguably the most interesting of the three. The book tells a spellbinding story of a man with eccentricities that went well beyond a fascination with rocketry and included a penchant for the occult. He became an acolyte of the English writer and magician Aleister Crowley, who was the founder of a cult that practiced rituals of magick, "the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will." Crowley, who called himself "666" and "The Great Beast" (among other things), was dubbed the "wickedest man in the world" by the British press. His Ordo Templi Orientis (which claimed descent from the Knights Templars and the Bavarian Illuminati) was by no means the most bizarre cult in freewheeling 1930s California, but it was strange enough.

Pendle's book follows the 1999 biography Sex and Rockets: The Occult World of Jack Parsons, by a writer using the pseudonym John Carter. Strange Angel is longer and gives a more nuanced portrait of the subject's conflicted and contradictory personality. Pendle also seems to have had access to some biographical sources unavailable to Carter. Sex and Rockets, however, provides more details about Parson's occult rituals and has better photographs.

The cover of Strange Angel (above) shows a young, resolute Jack Parsons examining two wires protruding from an odd cylindrical object—perhaps some piece of scientific equipment? The object is, in fact, nothing less than a large pipe bomb. This photograph—printed on the cover as a mirror image—was taken during a famous 1938 trial in Los Angeles in which Parsons testified as an explosives expert and built a replica of a bomb that had been used in an assassination attempt. He was only 23 at the time. This is the young, self--confident rocket scientist and explosives expert, only a few years from his greatest success, which was followed by his equally rapid plunge from science into magick, and from there to his death. The photo is oddly prescient: Just 14 years later, Parsons was killed in a mishap with his own explosives.

Strange Angel has a strong narrative drive and reads like a novel—except that a novel has to be plausible, whereas the life of Jack Parsons, poet, magician and rocket pioneer, had no such constraint.

Lord's Astro Turf, a much shorter book, looks at the same history from a different direction. Her story centers on her personal search to understand her father, who was an aerospace engineer in the early days of JPL's interplanetary probes. In narrating her quest, she weaves backward and forward in time, exploring the history of JPL and interviewing present-day engineers who have worked on the Pathfinder and Mars Exploration Rover missions.

Lord is more interested in Malina than in Parsons (although the latter does, of course, play a costarring role). Her chapters on Malina, titled "The Rockets' Red Glare, Parts I and II," form the heart (and most interesting portion) of her book.

In 1935, rocket engineering had barely advanced from the technology developed by Sir William Congreve (whose rockets, fired by the British in the War of 1812, inspired the "rockets' red glare" line in "The Star-Spangled Banner"). Indeed, little improvement had been seen since the Chinese had used black-powder rockets in warfare a thousand years earlier. That was about to change rapidly as a result of work on liquid-fueled rockets being done on three fronts: in New Mexico by Robert Goddard; in Germany by Wernher von Braun's Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR), or Society for Space Travel; and in California by GALCIT's Rocket Research Group—the "Suicide Squad," consisting of Parsons, Forman, Malina and their coterie.

From Strange Angel

By 1938 members of the Suicide Squad, no longer allowed to carry out their experiments on the Caltech campus, were testing their engines outside Pasadena in the Arroyo Seco, which later became the site of JPL. They reveled in their nickname. Parsons would dance and chant poetry—most notably Crowley's "Hymn to Pan"—before rocket tests. (Von Kármán called Parsons a "delightful screwball.") Slowly and painstakingly, they developed a practical theory of rocket motors. They also invented propellant combinations that were robust and storable. What is more important, these new liquid and solid propellants fueled working engines—in contrast to the concoctions that preceded them, which had chiefly fueled explosions (hence the group's nickname). In the early days Parsons, Forman and Malina were the driving force, although others of course contributed as well.

The war brought respectability and badly needed funding to the rocket-crazy trio. Malina sold the U.S. Army on the utility of rocket boosters, which were tagged Jet-Assisted Takeoff (JATO) units, to boost overladen bombers from short runways. With von Kármán as its titular head, GALCIT suddenly had a funded rocket-research project. "We could even expect to be paid for doing our rocket research," Malina marveled. And, thanks in good part to the trio's diligence and to the chemical genius of Parsons, their experiments succeeded. Both Pendle and Lord recount how the men launched a small airplane, an Ercoupe, into the air on rocket power. Within a year they incorporated Aerojet to manufacture the JATO units. In 1944, GALCIT was renamed the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. (At the time, the word rocket, which was associated with Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, was not taken seriously, so jet was substituted, having been deemed more appropriate for marketing purposes.)

If the story had stopped at 1945, the success of Malina, Parsons and Forman would have been a classic American tale of triumph against long odds, illustrating the merits of a small, dedicated technical team. The three men reinforced one another. Malina, guided by the genius von Kármán, reined in the impulses of the other two men, who were eager to try whatever idea happened to spring to mind. Malina insisted on gathering rigorous data. The enthusiasm of Parsons and Forman for experimentation, on the other hand, kept Malina focused toward building actual rocket engines, not just solving equations on paper.

In October 1945, the WAC Corporal rocket, the final achievement of the GALCIT rocket project, flew to an altitude of more than 70 kilometers, becoming the first American rocket ever to exit the Earth's atmosphere. (When I started flying model rockets 20 years later, my first launch was a scale model of the WAC Corporal. I did not know its venerable history!)

But the story did not end with the WAC Corporal launch. The descent and fragmentation of the team was as chaotic and complicated as its rise had been triumphant. Of the original three, only Frank Malina was still at JPL when the WAC Corporal penetrated into space, and he was only to remain for another year.

Malina's fate diverged from that of Parsons in 1945, after the trio had succeeded in their original objectives. Parsons and Forman, ill-suited to running a business, were persuaded to sell their Aerojet shares for a modest amount: Parsons netted enough to buy a house, with some money left over to invest—but if he had kept his stock another 15 or 20 years, it would have been worth millions. The buyout was a move on the part of Aerojet to dissociate itself from the increasingly bizarre behavior of Parsons, who was experimenting with "sex magick" and running a bohemian commune and an occult temple out of his home. His behavior got crazy here, as he tried—but ultimately failed—to be as successful in his experiments with magick as the trio had been in their rocket experimentation.

Malina kept his Aerojet shares. It was a youthful interest in the Communist Party that catalyzed his departure from rocket research. After the war, official attitudes turned increasingly toward paranoid anticommunism. Lord puts together a good case that Malina indeed had close associations with the Communist Party in the 1930s, but she also notes that, like most liberals of the era, he broke completely with communism following the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939.

As Lord points out, although being an ex-Nazi did not preclude being considered a solid American citizen, being an ex-Communist, or even having attended a single meeting of the Communist Party, branded one forever as un-American. Malina's youthful interest resulted in increasingly hostile attention from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Meanwhile, the development of rockets as a means for delivering atomic warheads, an application the young trio had never imagined, increasingly disturbed Malina's conscience. In 1947 he left Pasadena, and rocket research, accepting a job offered by Julian Huxley to join the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Paris.

Moving to Paris did not solve Malina's problems with the FBI. In 1952, he was indicted for having failed to list his Communist Party membership on an old security questionnaire from Caltech. He was declared a fugitive, to be arrested if and when he returned to the United States. Malina's stock in Aerojet gave him enough savings to live independently. He went on to have a successful career as an artist and sculptor, and founded the interdisciplinary magazine of arts and sciences Leonardo, which still exists today.

Lord recounts the early days of JPL's founders in pieces, alternating with chapters about her family and about present-day JPL. Her story is weakest, oddly enough, when she talks about her own family and her experiences growing up in the 1950s and early 1960s with an aerospace engineer for a father. Her characterizations of engineers rarely rise above stereotype, and her analysis relies on pop psychology and overused metaphors: Rockets are always "phallic" and "tumescent"; the launch process is "steeped in left-brain, masculine communication patterns." Even mild engineering humor is opaque to her.

In one chapter, Lord blames her father for failing to encourage her to study science and engineering. Her family stories, though, give the opposite impression. A pressure-suit helmet given to her by her father was her favorite childhood toy, and she writes about how she and her father spent "twenty-four weekends" together building model airplanes, which she lists lovingly by name. She states that she was brilliant in all subjects in school, except for having "no aptitude" for "rock-hard, number-filled courses." Yet she never thinks that her lack of interest in math might have been a factor in her father not encouraging her to enter engineering.

Lord's cultural critiques are a bit shallow. We hardly need her exaggerated scorn to tell us that in the '50s and '60s sex roles were stereotyped, or that families who are apparently happy can conceal tragedies.

Some of her accusations are oddly off-target. To illustrate intolerance of homosexuality at JPL in the 1960s, she relates the British persecution of mathematician Alan Turing. It is no particular revelation that workplaces of that era were peculiarly intolerant of homosexuality, but it is odd that Lord had to look back several decades and across an ocean to find a noteworthy example. (The main example she finds of intolerance of homosexuality at JPL is that a 1989 seminar titled "Homophobia in the Sciences" did not rate an announcement in the JPL in-house publication.)

Lord's interviews and capsule sketches of many of the engineers involved in Mars projects past and present at JPL (many of whom I've worked with) are a bright point of the book. The work environment in engineering has advanced since the '50s and '60s, and she excels at personalizing the people involved in missions. In the process, she demonstrates that engineering is no longer the exclusive fraternity of white men with slide rules and crew cuts.

These two books paint a portrait of a remarkable time and place—Pasadena before and after the Second World War, when a small band of enthusiastic kids experimenting in an empty arroyo created a fantastic invention that has shaped today's world. Indeed, when the first American satellite, Explorer, was launched in 1958, the Army team led by von Braun built the first stage of the rocket that launched it—but the upper stages, and the satellite, are direct descendants of the rockets built by the Suicide Squad.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.