This Article From Issue

September-October 2002

Volume 90, Number 5

DOI: 10.1511/2002.33.0

Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World's Undeciphered Scripts. Andrew Robinson. 352 pp. McGraw-Hill, 2002. $34.95.

As longtime literary editor of the Times Higher Education Supplement in London, Andrew Robinson is well able to interpret the arcana of scientific discoveries for the general public. In Lost Languages, he explains the principles of three famous decipherments and applies the insights gained to an understanding of several undeciphered scripts—Linear A, the Etruscan alphabet, the Phaistos disc, and the Meroitic, Proto-Elamite, rongorongo, Zapotec, Isthmian and Indus scripts.

Robinson shows successful decipherments to have been breakthroughs in a process of mistakes, false starts and genuine insights. Although the decipherers were indebted to earlier researchers, they often were investigating against the received wisdom of their time.

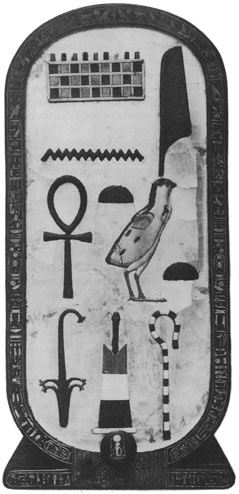

Jean-François Champollion, who "cracked" the code of Egyptian hieroglyphs in 1823, was fortunate to have the opportunity to work with the Rosetta Stone, which presented a text in three languages: Egyptian hieroglyphic, Egyptian demotic and Greek. He could translate the Greek, and his knowledge of Coptic enabled him to equate each name in the Greek text with a cartouche (a small group of hieroglyphs enclosed in an oval ring) on the stone and to work out a true decipherment.

From A Matter of Degrees.

Michael Ventris, who deciphered the Minoan Linear B script in 1952, had to use logical analysis. He thought at first that the language of Linear B (now dated to c. 1450 b.c., two or three centuries before the Trojan War and 600 to 700 years before the earliest-known inscriptions in classical Greek) might "correspond . . . closely to Etruscan." Alice Kober had identified patterns in Linear B—five groups of words with three words in each group—that Ventris called "triplets." Kober had thought these were declensions, but Ventris guessed that each triplet reproduced the name for a Cretan town and the male and female residents of the town. He was then able to apply new phonetic values for the signs in those names to fresh words on the Linear B tablets and obtain recognizable archaic Greek words. After Ventris announced his discoveries on British Broadcasting Corporation radio, Carl Blegen supplied the clinching evidence, successfully using Ventris's proposed phonetic values to read a Linear B tablet from Pylos that Ventris had never seen.

Decipherment of the Mayan glyphs proceeded from logical reconstruction. Recognition of the signs for numbers permitted equating them with dates of the Mayan calendar. A sign list compiled as a sort of "alphabet" in the 16th century by Fray Diego de Landa, a Franciscan friar who served as bishop of Yucatán, was incorrect in some of its interpretations but offered a number of useful clues. In 1952, Yuri Knorozov was the first to suggest that the glyphs were phonetic symbols. Later in the decade, Tatiana Proskouriakoff hypothesized that a set of sculpted inscriptions from Guatemala depicted rulers of Piedras Negras, along with the ruler's birth date and date of accession, and it became obvious that Mayan monuments recorded history. Eventually it was recognized that Maya scribes mixed phonetics with logograms (whole-word semantic symbols such as "+" or "&") in unpredictable ways.

Four examples of the undeciphered scripts illustrate the contents of the book, which presents eight mysteries in all. The Kingdom of Kush, whose principal city was ancient Meroe, on the banks of the Nile in what is now Sudan, employed Egyptian hieroglyphs in its script as late as the first century a.d., and sometimes they appeared alongside Meroitic hieroglyphs. Francis Llewellyn Griffith of the University of Oxford was able between 1909 and 1911 to draw up a Meroitic "alphabet" with phonetic values. But since then, using bilingual Egyptian/Meroitic texts, it has been possible to figure out the meaning of only 26 words; further progress has been stymied. It appears that the likeliest line of investigation will be to compare signs with the vocabulary and structure of African languages now spoken in the area.

Etruscan deceives. Its decipherment seems to be within reach—there are a fair number of inscriptions, written in a modified Greek alphabet, that scholars can read but in large part do not understand. Some words for place names and characters in mythology are known; Etruscan mirrors show recognizable scenes from mythology, with characters labeled.

Linear A, undeciphered, tantalizes, because about 80 percent of its signs resemble those of Linear B. Its system of numerals seems to be fairly clear: On several tablets, a term for "total" appears at the bottom of a tablet that includes a series of numbers. The numbers add up to the total given, instilling confidence that we understand at least these units. Attempts to show that Linear A represents a known language of the Aegean world, however, have not been successful. All but a few scholars agree that the language of Linear A cannot be Greek, and the idea that it represents a Semitic language has been rejected by nearly everyone. An Anatolian language (perhaps Lycian) remains a possibility.

Sanskrit and early Dravidian, the ancient languages of India, seem to be the keys to deciphering the highly challenging script of the Indus Valley civilization of the third millennium b.c. in what is now Pakistan and northwest India. As with other languages, a photographic corpus of drawings, a sign list and a concordance must be compiled before decipherment will be possible. Work has proceeded along these lines for inscriptions on some 3,700 objects from the Indus Valley, most of them seal stones with very brief inscriptions (the longest has only 26 characters).

As Ventris once noted, before Champollion the oldest known languages were Greek, Latin and Hebrew, all preserved in records that date back only to 600 b.c. The decipherments of the 19th and 20th centuries have expanded our knowledge of the use of writing to represent human speech. The logical analysis employed in attempts to decipher ancient scripts contributes significantly to our understanding of literacy in all of its ramifications. Robinson's descriptions of such analysis, and his accounts of both successful and unsuccessful decoding attempts, are clear, provocative and stimulating.—William C. West, Classics, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.