Tip-of-the-Tongue States Yield Language Insights

By Lise Abrams

Probing the recall of those missing words provides a glimpse of how we turn thoughts into speech and how this process changes with age

Probing the recall of those missing words provides a glimpse of how we turn thoughts into speech and how this process changes with age

DOI: 10.1511/2008.71.234

Our ability to use words is a critical part of our species' mastery of language. In practice, that mastery comes down to saying what we mean without having to think too much about it. When we have something to say, we first retrieve the correct words from memory, then execute the steps for producing the word. When these cognitive processes don't mesh smoothly, conversation stops.

pintailpictures/Alamy

Suppose you meet someone at a party. A coworker walks up, you turn to introduce your new acquaintance and suddenly you can't remember your colleague's name! My hunch is that almost all readers are nodding their heads, remembering a time that a similar event happened to them. These experiences are called tip-of-the-tongue (or TOT) states. A TOT state is a word-finding problem, a temporary and often frustrating inability to retrieve a known word at a given moment. TOT states are universal, occurring in many languages and at all ages.

People resolve TOT states using a variety of methods. Some are conscious strategies, such as mentally going through the alphabet to find the word or consulting a book or person. However, the most common method for resolving TOT states is an indirect approach: relaxing and directing one's attention elsewhere. The missing word suddenly comes to mind without thinking about it. These "aha!" moments are known as "pop-ups." The purpose of this article is to explore the cognitive processes that cause pop-up resolutions and to document changes in these processes with healthy aging. The ability to resolve TOT states changes significantly in old age, which is particularly important because older adults have more TOT states than do younger adults.

What causes a TOT state in the first place? To answer that question, we must understand how speech is produced. On average, people talk at a rate of about two to four words per second and make an error every 1,000 words or so. The rarity of errors is remarkable, given the complex, albeit unconscious, mental gymnastics that translate a concept into spoken words.

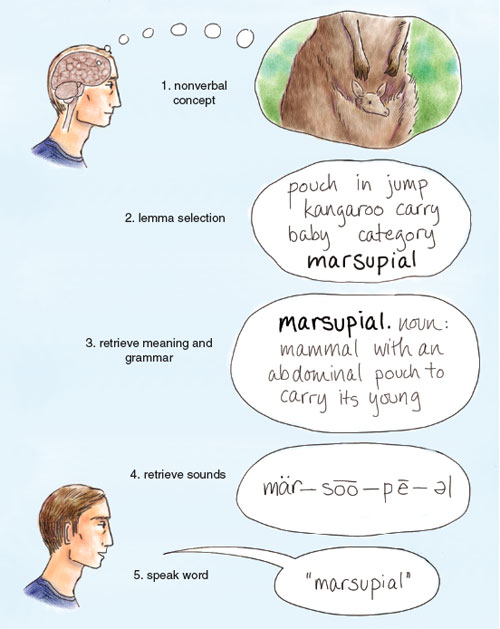

These cognitive processes begin with a nonverbal message, a general idea of what the speaker plans to say. This step is followed by a second process, called lexical access, in which a word or words are chosen to carry the message. During lexical access, language centers in the brain select a lemma, a lexical representation that is consistent with the meaning (semantics) of the word to be expressed and contains its grammatical (syntax) properties. Following lemma selection, the brain retrieves the neural blueprints for the sounds that make up the word (its phonology) and sends those plans to the system that directs speech articulation. Muscles in the mouth, throat and diaphragm work together to produce speech.

The stage for retrieving semantics and syntax is separate from the one for retrieving phonology, but debate continues about how these stages interact. According to "stage" or "discrete" theories of speech production, the stages are independent of one another. Discrete theories emphasize sequence: a lemma must be selected before phonological encoding. Alternatively, "interactive activation" theories of speech production say the cognitive processes for lemma selection and phonological encoding somehow communicate back and forth. In other words, interactive activation theories allow phonological processing to influence lemma selection; discrete theories rule out this possibility.

Both types of theories agree that TOT states arise when the brain selects the appropriate lemma but fails to encode its phonology. Because lemma selection has already happened, TOT states are marked by a strong "feeling of knowing"—we know we know the word. For example, when I see a student whom I taught several semesters ago, I typically cannot retrieve her name (although I will recognize it once she says it). But I can often remember other information about her—what she looked like, where she sat in the classroom, whether she was a good student. With respect to phonological encoding, an incomplete retrieval might lead us to recall the first letter of the word or its number of syllables. But to retrieve the whole word, its entire phonology must be available and fully encoded. Failure in the latter process causes a TOT state.

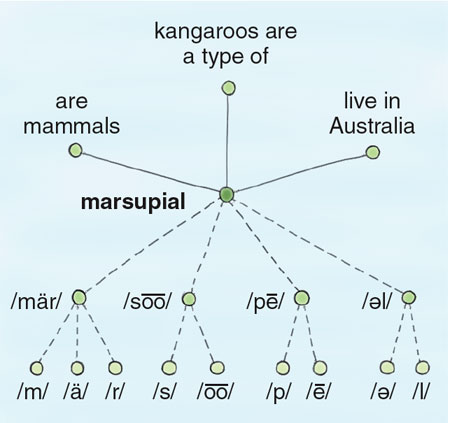

Our internal representations of words are housed in semantic and phonological systems. The semantic system contains all of our knowledge about word meanings, and the phonological system contains the words' sounds. Figure 3 shows the word marsupial broken down into its syllables and corresponding sounds, or phonemes. Solid lines in the figure represent the fact that retrieving semantic knowledge about words is usually easy; we tend not to forget the meanings of words in our vocabulary. Dotted lines indicate the weak connections between the word and its sounds, and those weak connections are the cause of TOT states.

Why do connections between words and their phonology weaken? Two cognitive psychologists, Deborah M. Burke of Pomona College and Donald G. MacKay of the University of California, Los Angeles, proposed the "transmission deficit model" of TOT states, which suggests three main causes. One is low frequency of use: Words used infrequently have weaker connections to their sounds, which is why TOT states typically occur for relatively rare words such as marsupial. A second cause is nonrecent use: A word not accessed recently will also have weaker connections. For example, the names of people we haven't seen or talked to in a while, such as our fourth-grade teacher, are more susceptible to TOT states. The third cause is normal aging: As we get older, all connections between words and sounds weaken independently of the other factors.

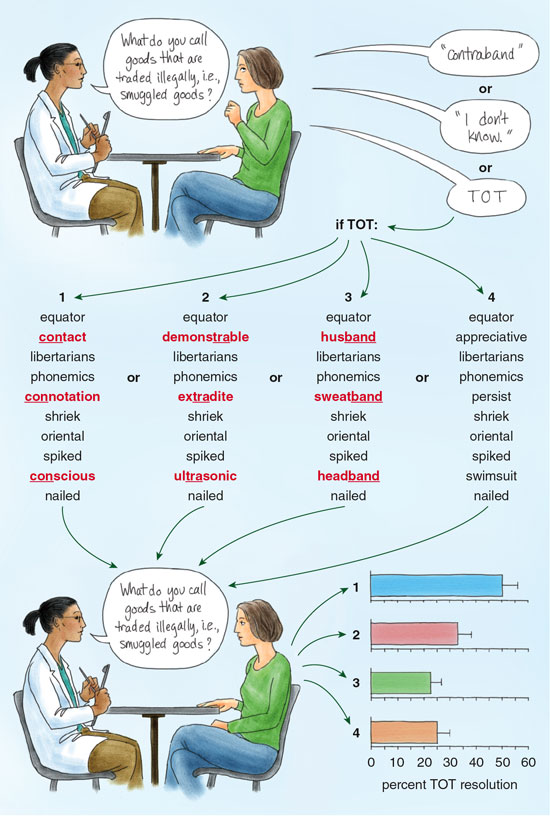

This model of weakened phonological connections makes an important prediction. If weakened connections to a word's phonology cause TOT states, then TOT states should resolve when the missing phonology is encountered in some way that strengthens those connections. It's possible to test this prediction with a simple interview. The test protocol often uses a computer to present the questions, which minimizes variability between trials. An interview session begins with a list of general-knowledge questions whose answers are the "target" words. As each question comes up on the screen, the study participant indicates whether they know the answer, don't know the answer or know it but can't quite recall the word—experiencing a TOT state, in other words. When the question elicits a TOT response, the computer gives a list of words to read that are phonologically related or unrelated to the target, then presents the same question a second time. By comparing the TOT responses to the first and second readings of the question, this protocol tests whether presentation of a word's phonology increases TOT resolution by aiding target retrieval. For the experiment to reflect pop-up resolutions, participants must remain unaware of the connection between the listed words and the target. Otherwise, they could use a directed-memory search for the target, which involves different processes from those where the TOT word pops into mind without conscious effort.

In 2000, Lori E. James, now at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, and Burke used this protocol to test the idea that phonologically similar words could prompt TOT resolution. For half of the TOT states, participants read aloud a list of words that cumulatively contained all of the syllables of the TOT word. For example, if a participant had a TOT response for the target abdicate, he might be asked to read aloud a list of ten words, including abstract, indigent, truncate, tradition and locate, each of which contains a syllable of the target. For the other half of TOT states, participants read a list of 10 phonologically unrelated words. Participants then saw the question again and attempted to retrieve the target.

The results showed that people resolved more TOT states after reading phonologically related words than they did with unrelated words. Speaking and hearing the syllables of the target, even when they were contained within other words, increased those sounds' recency of usage. This increase subsequently boosted the strength of those connections and enabled people to retrieve the target. James and Burke suggested that these results mimic how TOT states are resolved in everyday life, where we suddenly come up with the target, seemingly out of nowhere. In actuality, these pop-up resolutions of our TOT states are probably caused by encountering the target's phonology in some way.

The intriguing work of James and Burke inspired my colleagues and me to pursue additional experiments. We wondered, for example, if speakers needed the target's complete phonology to help resolve TOT states. In particular, we reasoned that because the first sound of a word was—obviously—spoken before the others, that it might be more critical for word retrieval. If this hypothesis were true, then strengthening connections to the initial phoneme might in turn strengthen the remaining phonological segments during a TOT state.

Using James and Burke's method, my former graduate student Katherine K. White (now a professor at the College of Charleston), then-undergraduate student Stacy L. Eitel and I conducted several experiments to test this idea. We presented general-knowledge questions and, following TOT responses, gave participants a list of words to read. On one list, the words were unrelated to the target. The other list had several words that shared the target's first phoneme. After the participants read the list, we presented the question again. We found that the phoneme-related list wasn't any better than the unrelated list at helping to resolve a TOT state. In retrospect, we realized that this finding mimics the real-life experience of knowing the first letter of a sought-after word but being unable to retrieve the whole thing.

We then discovered that word recall and TOT resolution require the entire first syllable, rather than just the first sound. Following TOT responses, we gave participants one of four possible word lists. Three of the lists contained words that were phonologically related to the target but shared only a single syllable—first, middle or last. The other list contained phonologically unrelated words. When seeing the question for the second time, reading words with the target's first syllable—but not the second or third—helped resolve TOT states relative to phonologically unrelated words. Thus, words like contact were helpful in recalling the target word contraband, but words like extradite and husband were not. These results suggest that a word's initial phonology is the key to its retrieval.

We also found that reading the words silently was as effective as reading them aloud in resolving TOT states. Therefore, it isn't necessary to either speak or hear the phonology, which broadens the possibilities for encountering phonological cues that help resolve TOT states in everyday life. This makes sense given that TOT states sometimes resolve when we are quiet and alone. Simply thinking about words or saying them to oneself can help retrieve the missing word.

It seems reasonable to expect that we can encounter the TOT word's phonology in more ways than the ones observed in the lab. Since I began studying this phenomenon, I've tried to analyze my own experiences with TOT states. I've found that most of the time when I resolve a TOT state, I don't know which word triggered it. This observation led me to wonder whether there are hidden ways of coming across phonological cues, ones that aren't as obvious as hearing or saying the first-syllable phonology.

Another former graduate student, Lisa A. Merrill, and I explored this question using a similar TOT-inducing slate of general-knowledge questions. However, this time, rather than giving the tongue-tied participants a list of words, we showed them a picture of some object and asked them to name it. Half of the time, these pictures had two possible names, and the less common name contained the target's first syllable. For example, for the target biopsy, one of the pictures could be labeled as either motorcycle or bike, where bike is the less-used name. The other half of the time, the picture name was unambiguous and had no phonological relationship to the target (helicopter, for example).

We discovered that people were more likely to resolve a TOT state for the word biopsy after saying the word motorcycle rather than helicopter. Why does motorcycle help, since it has no direct phonological overlap with biopsy? We think the reason is that motorcycle is strongly related in meaning to bike, which has a phonological connection with the target. Thus, even second-hand exposure to the first syllable of the TOT word, mediated by semantic connections, can help to resolve TOT states. It's not necessary to actually encounter or produce that phonology directly. Given the frequency of pop-ups in everyday life and the fact that most of them have no obvious link to recently encountered words, we believe that many TOT states resolve through this kind of mediated exposure to the target phonology.

Although many studies have validated the idea that words with phonologies similar to the target help to resolve TOT states, there is a caveat: In some cases, phonologically related words actually impede the retrieval of a target word. Burke and her colleagues showed that when TOT states are accompanied by an alternative word—a word that you know is not the right one—TOT states are less likely to be resolved. They also noted that these alternatives were often phonologically related and the same part of speech as the TOT word. Other speech-production studies also show that wrong answers are usually in the same grammatical class as the intended word—for example, saying "cool tart" instead of "tool cart." Both are adjective-noun phrases. We suspected that this pattern of preserving grammatical class when retrieving the wrong word might be significant for determining when phonologically related words help or hurt our resolution of TOT states.

In 2005, then-undergraduate Emily L. Rodriguez and I set out to test this idea. We again induced TOT states with general-knowledge questions, such as "What do you call a large, colored handkerchief usually worn around the neck or head?" The target word in this example is bandanna, a noun. When people experienced a TOT state, we asked them to read silently one of three possible word lists. One list contained a word with the same first syllable as the target and of the same grammatical class, like banjo (a noun). The second list included a word with the same first syllable but representing a different part of speech, like banish (a verb). The third list lacked phonologically related words. The participants then saw the question again and attempted to retrieve the target.

We discovered that the only cue words that were helpful were the ones from a different part of speech. Reading banish (a verb) helped resolve a TOT state for bandanna (a noun), but reading banjo (a noun) did not. These findings suggest that similar-sounding words in the same grammatical class as the TOT word may compete with the TOT word for production, rather than helping to produce it.

The issue of TOT states is of particular importance to older adults, as TOT states become more frequent as we get older. Furthermore, older adults experience more negative consequences of TOT states, including the perception of incompetence by themselves or others and withdrawal from social interactions. Therefore, the need to resolve TOT states is even greater for older adults. Are they, like college students, influenced by encountering phonologically related words? Although few studies address this question, it seems that people in their 60s and early 70s get the same benefit from phonologically related words as younger adults. On average, however, people in their late 70s and 80s have significantly less or no TOT resolution following phonologically related words.

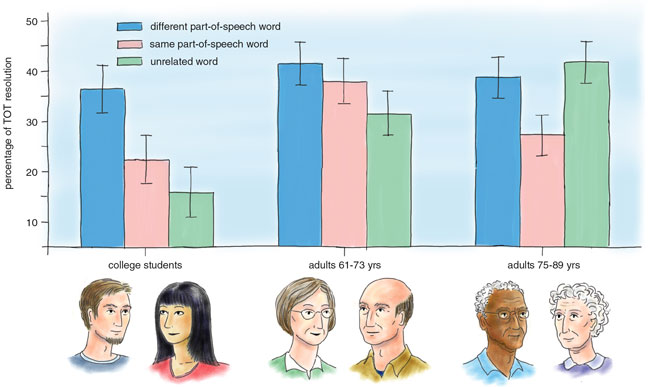

We have discovered that age can change the effects of grammatical-class selectivity in phonological cues. When my former graduate student Dunja L. Trunk (now a professor at Bloomfield College), Merrill and I compared TOT-resolution data from college students with those from adults aged 61-73 and 75-89, we found similar word-retrieval patterns in college students and people in their 60s and 70s. Thus, retrieval of bandanna improved after reading banish but not banjo. In contrast, adults in their late 70s and 80s did not benefit from reading banish, and furthermore, their retrieval of bandanna was worse after reading banjo compared with an unrelated word. In this age group, a phonologically related word actually makes TOT resolution harder when the words are in the same grammatical class. It seems that potential alternative words become more competitive for retrieval as we age, which has a real-world implication for TOT-resolution strategies. When having a TOT experience for the author of The Scarlet Letter (Hawthorne), asking for help could be counterproductive if the person suggests Thomas Hardy. Not only is the suggestion wrong, but it actually decreases the likelihood of TOT resolution for adults in their late 70s and 80s.

The study of TOT states and their resolution supports interactive activation theories of speech production. Our data show that phonological processing can strengthen the connections between a word's phonology and its lemma. The finding that parts of speech determine the benefit or cost of phonological cues tells us that grammatical class constrains the words we can produce. In the midst of a TOT state, a phonologically related word in the same class can compete for, rather than aid, retrieval. It is as if the retrieval process, having encountered a word with the right phonology (the first syllable) and syntax (part of speech), has difficulty moving on to find the word that has these attributes plus the right semantics.

With respect to practical implications, people spontaneously resolve TOT states many times a day. It seems as if the desired word suddenly pops into mind. However, these resolutions are not accidental. The TOT word's phonology became available for some reason—you heard it, you thought it or you said it. These pop-up resolutions become more important as we age because word-finding problems have negative effects for older adults: They disrupt conversations, create a perception of incompetence and ultimately discourage older people from talking, which only makes the problem worse. Understanding the factors that influence pop-up resolutions is critical for facilitating older adults' communication. Clearly, speech production isn't as simple as producing whatever words come to mind. The next time you have a frustrating tip-of-the-tongue experience, try to appreciate its significance in helping us to understand the complex processes that underlie our ability to speak.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.