This Article From Issue

November-December 2024

Volume 112, Number 6

Page 322

Melissa Skrabal was 30 meters up in a live white oak tree in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. As an undergraduate member of a research team that had taken tree-climbing training in order to pursue slime molds (or myxomycetes) high in the canopy, she was following the thin black tracks that slime molds leave on tree bark. Skrabal was descending on a harness and rope, and she finally came upon some tiny fruiting bodies. When she got back down to the ground, she showed her samples to the team’s lead researcher, Harold W. Keller, who says that as soon as he saw them, he knew that Skrabal had found something special—and he also knew right away that it was a new species. This tiny organism had spore cases that glittered with a jewellike iridescence. Later, he and his collaborators at the University of Buenos Aires used scanning and transmission electron microscopy to determine that the fruiting bodies got their glimmer from their surface structure, not from pigmentation. Keller, Sydney E. Everhart, and Courtney M. Kilgore describe their team’s research experiences and the surprisingly wide range of forms taken by slime molds in “The Myxomycetes: Nature’s Quick-Change Artists.”

Scientific discovery is rarely so instantly gratifying; sometimes it can take decades for a discovery’s importance to be fully realized. Philip A. Rea has written previously in American Scientist about the tortured routes that some medications have taken from the point of first being isolated to finally arriving at a pharmacy. In “Gliflozins for Diabetes: From Bark to Bench to Bedside,” Rea discusses the history of a class of diabetes drugs known as gliflozins, which target the kidneys instead of the pancreas or liver. Gliflozins are now blockbuster drugs, but the path to their discovery began in 1835, with the chance relocation of a scientist’s apple orchard. After the trees had been dug up, some researchers were inspired to explore the medicinal potential of their root bark, knowing that bark extracts of other trees had been found to be useful in treating fever. A few decades later, other researchers were able to make the connection that apple root bark extract would increase sugar in the urine but decrease it in the blood. It took until the 1930s to show the mechanism, and until the 1960s to understand it on a cellular level. The substance languished because of its side effects, and it wasn’t until the early 2000s that derivatives were found that were safe and effective.

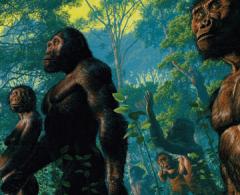

Sometimes scientific discoveries are instantly exciting, and their influence goes beyond their contribution to the data. That’s the case for the hominin fossil known as Lucy, says paleoanthropologist Bernard Wood, writing in this issue to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Lucy’s discovery. In “Paleontology’s Superstar,” Wood explains that this hominin fossil was rare in that all the bones were known to come from one individual, so that even though the skeleton is incomplete, it is possible to project correct bodily proportions for Lucy. Having been given the name Lucy is perhaps the reason that this fossil continues to be one of the most recognizable paleoanthropological discoveries, even though other fossils may have been more pivotal or better preserved. Her star status may have given Lucy an outsize influence on the interest in and development of paleoanthropological research in Africa for decades.

What scientific discoveries have inspired your work? Have you had the opportunity to make a firsthand discovery that you knew would change your career from that point onward? Join us on social media or send us a message through our website to tell us about it.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.