The Flavor of Serendipity

By Gary K. Beauchamp

Experience with the taste of ibuprofen led to the identification of anti-inflammatory properties in extra-virgin olive oil.

Experience with the taste of ibuprofen led to the identification of anti-inflammatory properties in extra-virgin olive oil.

It was in 1999 in Erice, a medieval town in western Sicily situated atop a mountain overlooking the sea, that I first smelled, sipped, savored, and swallowed pure liquid fat out of a glass.

I was at a meeting on the science of molecular gastronomy, which included physicists, chemists, biologists, chefs, food writers, and others fascinated by the science of cuisine; we were sitting around tables in old stone buildings. As a psychobiologist who researches the perception of taste, the meeting was squarely in my area of interest. Ugo Palma, the meeting organizer and a physicist at the University of Palermo, poured freshly pressed extra-virgin olive oil from his family’s farm into wineglasses for a traditional tasting.

My first impressions were mixed. It seemed very odd—indeed a bit disgusting—to drink liquid fat. Nevertheless, I sniffed and savored and swallowed as directed by Ugo. While the oil was in my mouth, it gave a soft and not entirely pleasant oily impression. When swallowed, it slid down smoothly. But, a few seconds later, I felt a strong stinging or burning sensation in the back of my throat. This burning sensation grew in strength until I coughed; others in the group coughed in concert.

Tom Dunne

To me, the sensation was startlingly familiar—but not in association with olive oil or any other food. Instead, it was identical to the sensation I had experienced when swallowing the liquid form of ibuprofen, the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) discovered in the 1960s, when scientists were looking for an alternative to aspirin and its potentially serious side effects. I instantly wondered: Could there be a natural anti-inflammatory agent in extra-virgin olive oil? Could its consumption over a lifetime underlie (in part) the well-known health benefits of consuming a traditional Mediterranean diet?

Over the years I have had numerous crazy “insights,” although virtually all were ephemeral. However, this one seemed so clear that I was loath to dismiss it. And, 20 years later, growing evidence indicates there is something to it. But it’s also an interesting example of how background interests and experience can provide inadvertent preparation for making serendipitous connections, in this case between the pungent sensation of extra-virgin olive oil and its pharmacology.

The word taste has two meanings in the realm of food, one scientific and the other colloquial. The colloquial meaning more connotes flavor, and refers to the overall perception of foods and beverages, which includes not only their taste, but also their smell and their somatosensory characteristics (those that relate to touch, temperature, and pain). The scientific meaning of taste refers only to the sensations that are mediated by specialized taste receptors located, in humans, mainly on the tongue and palate of the oral cavity. (Recently, taste receptors have been found in other organs, such as the gut, but those don’t contribute to our sense of taste.) These molecular receptors are connected to specific, taste-related parts of the brain. The human sense of taste in this scientific sense can be characterized by a small number of primary categories: sweet, salty, umami, sour, and bitter. The first three presumably serve to identify and motivate consumption of foods that are rich in carbohydrates, sodium, and amino acids and protein, respectively. Sour taste may exist to ensure avoidance of unripe fruits and other acidic irritants. Bitterness inhibits excess consumption (by insects as well as mammals) of mainly plant-based compounds that can be toxic, but can have medicinal properties at lower concentrations; examples of such compounds include members of the nitrogen-based class alkaloids, such as quinine, caffeine, and strychnine.

The stinging in the back of my throat grew until I coughed, and to me the sensation was startlingly familiar.

These primary taste qualities have a long history in philosophical and biological thinking. Aristotle thought that taste and tactile senses were closely related. His list of primary taste qualities was very similar to what is currently accepted, but he did not list umami, which is a 20th-century addition. He also included astringent, harsh, and pungent, which we now know are a part of the somatosensory system rather than taste sensations. Yet it is very easy to see why Aristotle and others such as Galen and, even earlier, Indian philosophers discussing the concept of Rasa (which means taste) in Ayurvedic medicine, categorized these somatosensory stimuli with the sense of taste: They appear to be localized to the mouth, and they provide information about the chemical characteristics of food. And for many of these ancient philosophers as well as for more modern practitioners of traditional medicine, the “taste” of a plant has served as a signal of its potential pharmacological activity.

Much more recently, in an important but neglected body of work from the 1960s, psychopharmacologist Roland L. Fischer and his colleagues identified the oral cavity of a person as a pharmacological preparation in situ; they regarded the gustatory response as a sensory expression of chemoreception, meaning that the perception of taste could, in a broad sense, be an indicator of physiological efficacy. I was fascinated when I first read Fischer’s work while I was a postdoctoral fellow in the early 1970s, and had begun to wonder about why we “taste” what we do. What Fischer said seemed to make such good evolutionary sense, despite there being little experimental support for the idea. Fascination with this speculative insight played a role in preparing me for the discovery of an anti-inflammatory compound in olive oil.

With my colleagues at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, I conduct basic and translational studies of the senses of taste, smell, and chemesthesis (chemical-induced irritation, such as the burn of hot peppers). One of our consultations led to my familiarity with the taste of ibuprofen.

In the early 1990s, we were working with the company now known as RB on their cold and flu remedy, Lemsip. Sold almost exclusively in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries, this powder is dissolved in hot water to make a lemon-flavored drink. Its pharmacologically active ingredients were an anti-inflammatory drug (paracetamol, or acetaminophen) and a decongestant (phenylephrine hydrochloride). The company had wanted to replace the paracetamol with ibuprofen, but in tests, users complained that it “tasted bad” or was “bitter.” We were asked to make suggestions as to the nature of the bad/bitter taste and present strategies for eliminating it. My colleagues Paul Breslin and Barry Green (both with extensive experience tasting many things for science) and I tried both Lemsip and pure ibuprofen. However, we disagreed with the consumer reports that Lemsip “tasted” bad or was bitter. Instead, it had another very distinct and unpleasant sensory attribute: It burned the throat. Consumers had confused taste with somatosensation, just as Aristotle had done. And obviously, if you are sick with a sore throat, a medicine that adds to that pain is not welcome.

As researchers into taste and flavor, we found this sensory attribute—a sting or burn or pungency localized almost exclusively to the throat—to be very odd and unusual. In particular, it contrasted markedly with other irritants such as hot peppers (and their active ingredient, capsaicin) or carbonation, both of which stimulate many locations in the oral cavity. This insight led Breslin and Green to wonder whether there might be some novel sensory receptors in the throat that are particularly sensitive to ibuprofen.

Sensory scientists dream of the possibility of discovering new receptors or of finding novel sensory pathways, so my colleagues were thus eager to study ibuprofen “taste” in greater depth. And luckily for us, so was the company.

In this case, it turned out that both parties were to be only partly satisfied. In the course of their rigorous investigations into the sensory perception of ibuprofen, Breslin and Green discovered that if the pH of an ibuprofen solution was raised above 7 (neutral pH), then the throat burn nearly vanished. This result provided a potential solution to the practical problem—the company could just raise the pH of Lemsip. Unfortunately, there was a fundamental problem with this “solution.” A lemon-flavored drink with a pH above 7 no longer has the sour taste that is mediated by acid, so it would not taste lemony to consumers. Today, the anti-inflammatory compound in Lemsip is still paracetamol.

But this foray into studying the taste of Lemsip explains why I had extensive experience tasting liquid ibuprofen. Aside from the college subjects we hired to do sensory analysis, it is likely that few others in the world had ibuprofen tasting as part of their skill set.

My invitation to attend the workshop on molecular gastronomy in Erice in 1999 was lucky. It was a small meeting with approximately 40 participants from a wide range of backgrounds. My friend Harold McGee, who is notable for having written the scientific culinary bible, On Food and Cooking, wrote a mini-history of this series of meetings on his blog, Curious Cook. McGee notes that the term molecular gastronomy originated at the first meeting on the topic in 1992, before experimental cooking became prominent. The goal in coining this rather grandiose title was apparently to impress upon the funders in the Italian government that this kind of science was worthy of serious attention.

Tom Dunne

The meeting was characterized by a requirement that each participant conduct a food or flavor “experiment,” but in truth, what they usually did was conduct a demonstration. My contribution involved demonstrating our research that when salt is added to quinine water, it inhibits bitterness, thereby enhancing the sweet taste. This experimentation requirement was also the reason for Ugo Palma’s tasting of home-produced extra-virgin olive oil, and the resulting throat burn that recalled to me the similar sensation produced by ibuprofen.

Since that meeting, I have participated in olive oil tastings around the world and have even lectured for classes training olive oil “sommeliers-to-be.” The world of olive oil tasting is very curious. Most of the effort—particularly in Europe, where most extra-virgin olive oil is produced, and where regulations are most stringent—seems to focus on detecting often quite subtle “defects.” These defects are thought to reflect problems in growing the olives as well as problems in producing and storing the oil. They are mainly identified by smell and are described by terms such as fusty, musty, rancid, metallic, muddy sediment, and vinegary. Indeed, for an olive oil to be officially deemed Extra-Virgin by the European Union, it must have virtually none of these undesirable attributes. This oil is one of the only foods in the world that depends on human sensory evaluation for its official designation, although there are some organizations trying to supplant or at least supplement human sensory testing with chemical analyses.

The official scoring system in the European Union does identify three positive sensory characteristics of extra- virgin olive oils: fruity, bitter, and pungent. Fruitiness refers to the positive, attractive attributes of the odor of the oil. The other two present a conundrum. Bitterness in most foods is not a positive attribute. As mentioned earlier, most taste researchers believe that an organism’s ability to detect bitterness evolved to protect it against consuming potentially harmful foods, even though medicinal plants are often characterized by their bitterness. Could the bitterness of some extra-virgin olive oils be a sign of the presence of healthy compounds?

This same question arises with the third positive sensory attribute of outstanding extra-virgin olive oils, their pungency or throat-burning property, the sensation that I found so startling after first tasting the oil. The painful feeling commonly stimulates coughing, and first-time tasters generally find the experience as unpleasant as I did. So why is this sensation, which presumably exists to protect the organism from harm, considered a desirable attribute of extra-virgin olive oil?

These were the questions at the top of my mind as I experienced Palma’s oil. Could it be that this sensation signals the presence of a valuable, perhaps health-related compound? Much like the use of “taste” to identify traditional medicines, was the presence of this pungency signaling its medicinal attributes? Can it be a coincidence that some of the presumed health benefits of long-term use of ibuprofen—such as epidemiological studies showing a reduced incidence of some cancers and neurodegenerative diseases— coincide with many of the benefits of a Mediterranean diet rich in extra-virgin olive oil?

In the end, Palma gave me the leftover oil to carry home to Monell so we could test this unlikely but intriguing hypothesis.

Once I returned to Philadelphia, the first step was to ask Paul Breslin to taste Palma’s oil. I like to say that Breslin did so with alacrity and, having savored and swallowed the oil, asked me with puzzlement “Why did you put ibuprofen in this oil?” This account may be apocryphal, but it does make a good story. However, there is no doubt that Breslin agreed that the sensory impression in the throat was identical to what we had so often experienced when we were testing Lemsip and ibuprofen.

With Breslin’s confirmation in hand, we set out to see whether we could convince colleagues to put our question to the test: Does extra-virgin olive oil contain one or more compounds that both stimulate throat irritation and have anti-inflammatory activity? Breslin and I are not chemists, and this problem was first a chemical one: What compound is causing the throat irritation? We were lucky that Ferdi Naf of Firmenich, a large Swiss flavor and fragrance company, was intrigued by the idea. He induced two of his chemist colleagues based in the United States, Jianming Lim and Jana Pika, to work on the problem. Lim and Pika spent many months chemically dividing up fresh extra-virgin olive oil into different components, or fractions, and then taste-testing each fraction to see whether it irritated the throat. In the end they found only one such fraction, and additional analyses of it showed that it contained only a single compound that was apparently responsible for all of the throat irritation. Many of the other compounds in the oil samples were bitter, but it appeared at this point that we were looking to chemically characterize only a single compound.

Tom Dunne

After purifying and analyzing this compound further, its structure identified it as one of a large family of so-called minor compounds known to be in extra-virgin olive oil. This family is named the phenolics because they all contain a common chemical structure called a phenolic ring, which is based on a circle of six carbon atoms (this family of chemicals is also known to have antioxidant properties). One of the formal names for this throat-irritating compound is a mouthful: (-)-decarbomethoxy- dialdehydic ligstroside aglycone.

We finished confirming our identification in early 2002. To our dismay, we quickly discovered that this compound had previously been identified in extra-virgin olive oil (by Gianfrancesco Montedoro at the University of Perugia in Italy and his colleagues), so we had not discovered a novel compound. However, as far as we knew then, at least no one else suspected that the compound specifically irritated the throat and was thus, according to our hypothesis, a candidate anti-inflammatory similar to ibuprofen.

To provide further evidence that we had identified the correct compound, we went shopping for multiple varieties of imported extra-virgin olive oil. We then conducted controlled studies during the latter part of 2002 into 2003, in which we measured the amount of our compound in each of the oils and independently asked a panel of tasters to judge the intensity of throat irritation of these same oils. We found an almost perfect correlation between the level of irritation and the amount of the newly identified compound. Those oils that had high levels of the compound were very irritating, whereas those that had little of it produced almost no irritation. This result was strong circumstantial evidence that our identification was correct.

Tom Dunne

However, we soon had another shock. Unbeknownst to us, scientists led by Johanneke Busch at the company Unilever also had been pursuing a program of research on the chemistry of extra-virgin olive oil, and in 2003 they published a paper identifying our compound as the one that causes the throat pungency. We had been truly scooped, and I remember well the visceral sensation of dismay and despair when I read that paper—at almost exactly the same time that we identified the compound ourselves.

We still had a glimmer of hope, however. First, the final step in identifying an active compound entails synthesizing it from its simple constituents. Formally, this step is necessary because it is always possible that unknown minor constituents in an extracted sample of oil could instead be the active component. If the synthesized compound has the requisite activity—in this case irritation of the throat—then the identification is proven. Second, and perhaps more important, Unilever had no idea, as far as we knew, that this compound might have potent anti-inflammatory activity, as it was unlikely that anyone there had experienced the taste of ibuprofen.

My colleague, synthetic chemist Amos Smith, and his students were already hard at work on synthesizing this and related compounds, and they completed this difficult task by early 2003. Later that year we finally were able to sit around the same table at Monell where we had tasted Lemsip many years earlier, and taste the synthetic compound. It burned the throat, exactly as we had hoped! But then we had to wait for months before we could get Food and Drug Administration approval to ask others to taste our synthetic version of the natural compound. At last, we recruited a group of trained tasters to judge the potency of several concentrations of the synthetic compound. These data fit exactly with what the previous group of tasters had determined when they had judged the degree of irritation produced by each variety of extra-virgin olive oil.

A person on the traditional Mediterranean diet would consume a daily anti-inflammatory dose from extra-virgin olive oil roughly equivalent to that of a baby aspirin.

The availability of pure compound allowed us to take the final step—to determine whether it had anti-inflammatory activity. To our delight (and relief), it was indeed a natural anti-inflammatory compound with potency a bit greater than that of ibuprofen. Based on average consumption of extra-virgin olive oil in the traditional Mediterranean diet, a person on that diet would consume a daily anti-inflammatory dose roughly equivalent to that of a baby aspirin, which might account for some of the diet’s health benefits.

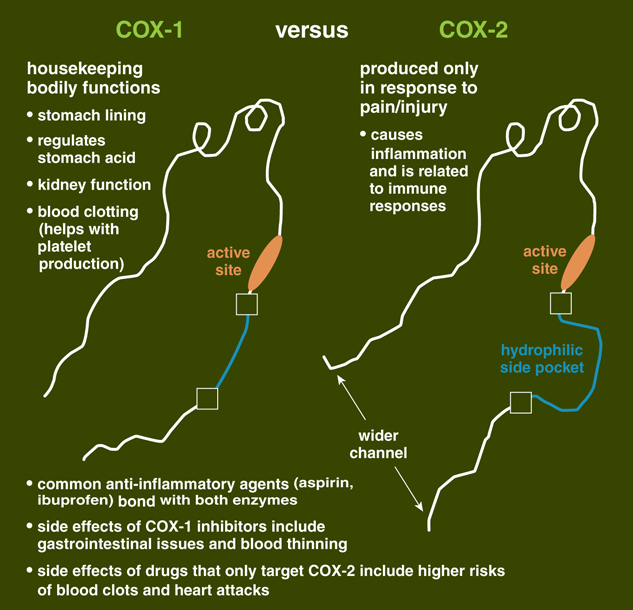

Using a commercially available kit, we were able to determine that the compound’s anti-inflammatory properties came from activity that was similar to that of other NSAID medications, in that it inhibits an enzyme involved in inflammatory processes. This enzyme, called cyclooxygenase (or COX), comes in two forms, COX-1 and COX-2. Both form substances called prostanoids, some of which cause inflammation and result in pain. However, COX-1 helps regulate many normal bodily functions, such as maintenance of the lining of the digestive tract, and proper kidney and platelet function. COX-2 is mostly found at sites of inflammation, and is the real target of anti-inflammatory drugs. But like many NSAIDs, the compound from extra-virgin olive oil inhibits both COX-1 and COX-2 function. (There have been some medications that only affect COX-2, but many of those agents have had cardiovascular and hepatic side effects serious enough that they were removed from commercial use.)

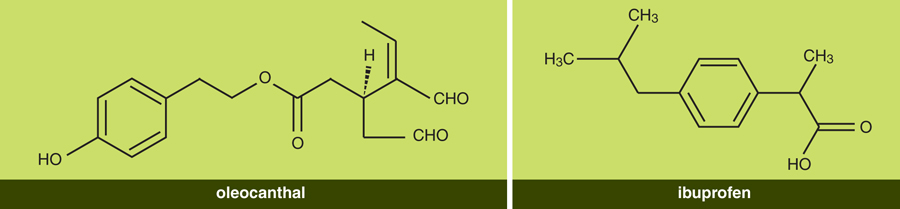

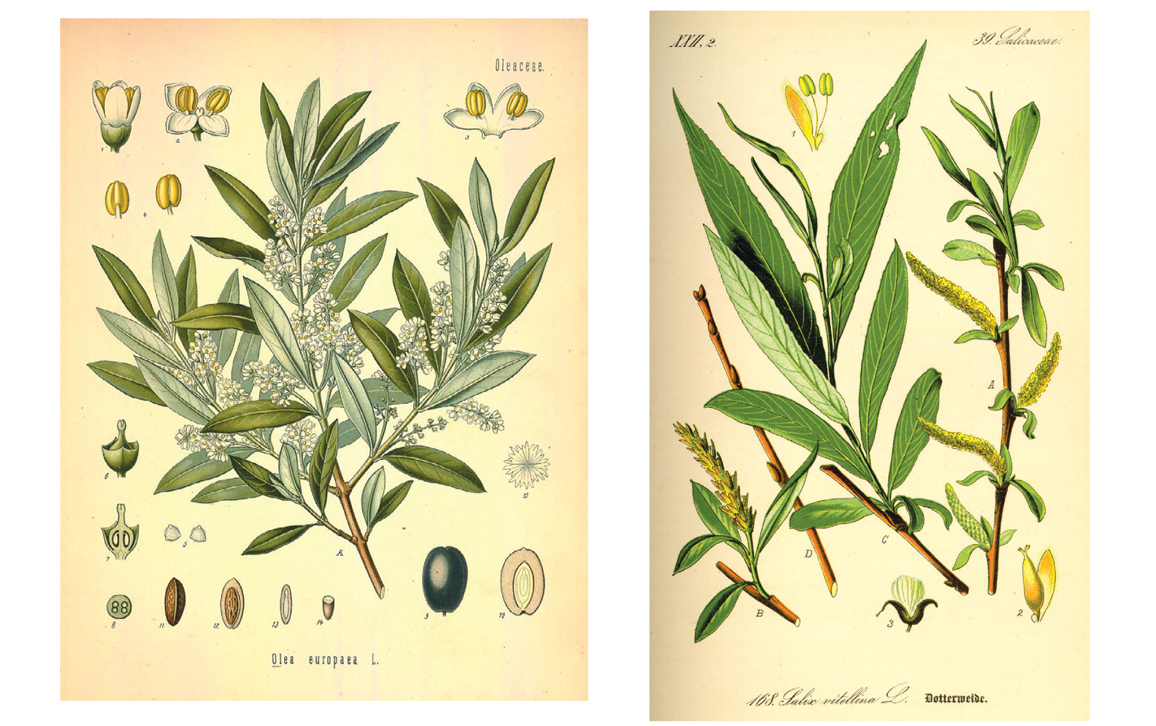

Once we had established the compound’s anti-inflammatory activity, the next order of business was to publish our results and tell our story, although our first paper in 2005 told little of this long process of serendipitous discovery. We decided that the compound we identified should have a simpler name than its long chemical designation, and Breslin suggested oleocanthal. The name is derived from oleo (for oil, as well as for the olive plant, Olea europaea), canth (for sting), and al (because the molecule is a dialdehyde, defined by its CHO groups). An earlier suggestion, oleotussin (the last part for cough), was rejected because it sounded too much like a common over-the-counter cough medicine.

Curiously, the naming of a familiar natural anti-inflammatory substance found in willow bark followed a similar course. That there is something in willow bark that reduces pain and fever was recognized thousands of years ago. In the mid-18th century, the active compound was identified from this and other plants as salicylic acid. The synthetic compound was sold commercially as the salt sodium salicylate. This compound had, however, at least two problematic side effects: It irritated the stomach, and it had a very unpleasant taste. By the end of the 19th century, chemists at Friedrich Bayer and Company were able to mitigate these problems to some degree by altering the molecule to acetylsalicylic acid, which they named Aspirin. The a in aspirin came from acetyl and the spir came from the first part of Spirea ulmania, the meadowsweet plant that was also a source of salicylic acid. Like us, the researchers had also considered another name, euspirin. But this suggestion was rejected because the eu, meaning good, often suggested an improvement in taste and smell. In any case, the powdered form was soon replaced by tablets, and after that its sensory attributes were moot.

Wikimedia Commons

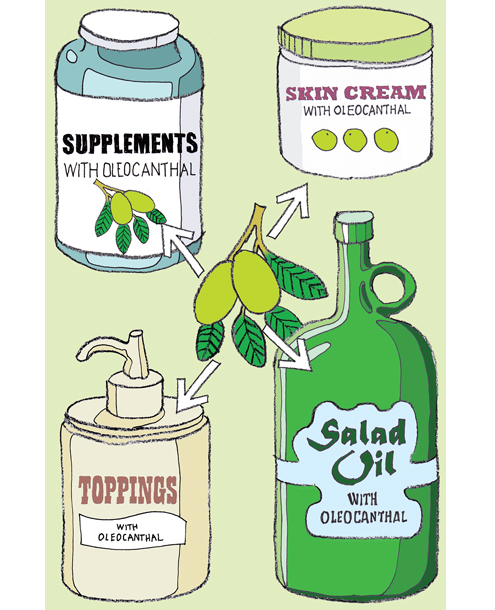

The made-up word Aspirin was an exclusive trade name that Bayer used in marketing until the end of World War I, and the word later became synonymous with all makes of the medication. In contrast, we were not able to exercise any control over the use of the term oleocanthal—we couldn’t maintain a trademark because we did not make a commercial product to trade in. Indeed, the term is now used in names for specific brands of olive oil, for skin creams (sometimes with slightly changed spellings), and in other products. And there is a move to put the compound into pills and tablets. Had RB made the original Lemsip formula in tablet form to begin with, taking taste out of the picture, this story would never have happened!

Although an easy-to-remember name will not ensure success, it can help focus interest and, in this case, further research. The week before our 2005 paper was published, an internet search for “oleocanthal” found 0 instances of the term; today such a search gives more than 100,000 hits. This number is fairly large, but it pales compared with hits for “molecular gastronomy” (20 times more) and “aspirin” (almost 1,000 times more). But we still have some years to catch up!

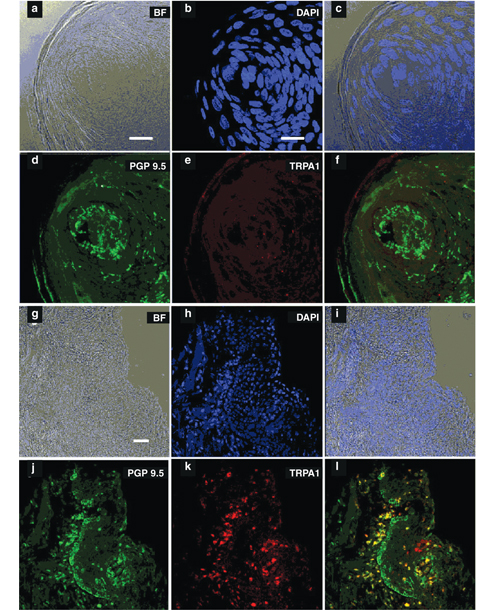

As is usual, our work has raised more questions than it has answered. One that puzzled us is why both ibuprofen and oleocanthal elicit such distinctive throat irritation. In a 2011 paper whose lead author was my colleague Catherine Peyrot des Gachons, we finally identified the receptors mediating this sensation—and they are not novel. They are ion channel receptors— proteins in membranes that can arrange themselves to form passageways across the membrane—that are known as TRPA1 ion channels (TRPA stands for transient receptor potential ankyrin). They respond to many irritants and are found throughout the body. So much for our hope of identifying a novel sensory pathway. The reason that the human throat (and not the mouth) is so responsive to oleocanthal seems to be that there are relatively few TRPA1 receptors in the human oral cavity, but many in the throat. TRPA1 is also highly expressed in the nasal passages, so if one puts oleocanthal (or ibuprofen) up the nose, which is not recommended, it will hurt.

Since 2005, a burgeoning number of medical studies have suggested that oleocanthal has efficacy in treating or protecting cells involved in diseases such as cancer, and in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, among others. Thus, there is substantial and growing interest among medical researchers, particularly in the Mediterranean region, in pursuing this study. There is even a small society headquartered in Spain called the Oleocanthal International Society, which has just had its fourth international meeting.

Given this interest and the promising results of quite a large number of studies using cell-based assays, why has progress in testing it in humans been so slow? First of all, no one owns a patent on the oleocanthal molecule itself (Monell does have patents on some of its uses). Without such intellectual property protection, even if the molecule turned out to be fantastically useful as a drug, companies could not recoup their research investment, because they could not have exclusive rights to sell it. This limitation has stimulated some researchers to synthesize novel chemical variants of oleocanthal that would perhaps be more potent and for which they could get exclusivity through the patent process.

From C. Peyrot des Gachons et al., 2011, Society for Neuroscience

Another roadblock is the limited amount of material available. The pathways for synthesizing the compound that have so far been published are long and difficult, and they probably are not cost-effective. Right now the only significant source of oleocanthal (and of a structurally similar molecule called oleacein that may also have health benefits) is expensive extra-virgin olive oil. The compound occurs in relatively small amounts in most oils, and the oil must be degraded to extract it, so this process too is probably not cost-effective in the long run. Alternative strategies for obtaining oleocanthal in bulk—such as by searching for it in other parts of the olive plant or in related plants, or by genetically engineering other organisms to produce it—might be solutions.

I hope that many new insights about the origins of oleocanthal, its production, its function within plants, and its medicinal benefits—and perhaps dangers— will be forthcoming. But what I most hope is that this serendipitous discovery, connecting apparently unconnected observations in a lucky pairing, will lead others to pursue research that may result in compounds that provide health benefits to large populations at minimal cost—much as oleocanthal’s cousin aspirin does. At the very least, this discovery has heightened interest in the benefits of consuming throat- irritating extra-virgin olive oil as a part of a healthful Mediterranean diet.

This story of discovery was certainly serendipitous, and it aroused my curiosity about serendipity in science in general, and even in the origins of the idea. In his 2004 book, The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity, sociologist Robert K. Merton follows the word serendipity from its first use—in a letter written by Horace Walpole in 1754, in reference to a story of three traveling princes in the ancient land of Serendip (an old name for what was then Ceylon) “who found certain clues they had not been looking for”—to its much more recent use by scientists and others to describe “the phenomenon of happy accidental discovery.” In Merton’s book and elsewhere, many famous discoveries are described as being a consequence of serendipity, including the discoveries of penicillin, x-rays, the structure of DNA, and even non- nutritive sweeteners (such as saccharine, sucralose, and aspartame).

Tom Dunne

Chance or luck alone cannot account for why certain individuals make unexpected connections and discoveries. As Merton points out, a particular kind of observer is necessary to make the connection between the unexpected observation and its possible implications; he quotes Louis Pasteur’s saying that “chance only favors the mind that is prepared.” In addition, recognition of the importance of serendipity in major scientific discovery also partially underlies the ultimate value of “basic research.” My former mentor and colleague Lewis Thomas made this point eloquently when contrasting applied with basic science: “Surprise [in basic science] is what makes the difference.”

Our “discovery” of oleocanthal may not compare with these widely known serendipitous discoveries, but the principles are the same: First, a prepared mind (experience “tasting” ibuprofen and an interest in the possible relationship between pharmacology and flavor perception), and second, a surprising observation (the same throat burn for extra-virgin olive oil as for ibuprofen) led to an interesting and hopefully significant line of research. Perhaps if more research papers gave some account of serendipity, we could better quantify its role in discoveries.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.