Communicating Science Through Visuals

By Barbara Aulicino

A Q&A with Felice Frankel

August 29, 2024

Science Culture Art Communications Aesthetics Photography Review Scientists Nightstand

Felice C. Frankel’s newest book, The Visual Elements—Design: A Handbook for Communicating Science and Engineering (The University of Chicago Press, 2024), is an accessible guide for scientists and engineers to learn how to create graphics to illustrate their work. She delves into the importance of thinking visually and what that really means, as well as provides case studies and advice from working designers. Frankel is an award-winning science photographer and a research scientist in the department of chemical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She answered some questions via email from art director Barbara Aulicino.

What did you go to school for, and how have your studies factored into your work today?

I received a BS from Brooklyn College, taking as many science classes as I could fit into the schedule. I was 16 when I started college and my parents didn’t want me to go to an “out-of-town school,” as we used to call it, which, incidentally, was the right decision. I mention that because it was easy to book the laboratory parts of the courses at night and walk home—sometimes four times a week. There is no question that science has always been a keen interest for me, even as a child. I remember playing with my older brother’s chemistry set and loving every moment, wondering why I was seeing the amazing changes in colors while adding this and that component. This lifelong interest in "the why" is what continues to amaze me in the labs at MIT!

Photograph courtesy of Felice C. Frankel.

Your book is about design and data visualization. What led you down the path of helping researchers and scientists to communicate their work visually?

For more than 30 years, I have worked with MIT researchers to develop photographs for journal submissions, and I observed a persistent disconnect between the exciting work in the laboratory and the quality of the graphics that are produced. Part of the challenge is that researchers want to cram every piece of data into a small journal space, but the other issue is that although many universities have a writing requirement, most offer nothing for visual literacy. The resulting illustrations are often confusing, unappealing, or, worse yet, inaccurate, which can have a significant effect on public understanding and perception of scientific research. I discussed the issue with my department heads in chemical engineering and mechanical engineering, and we started running a series of graphics workshops for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. That initiative snowballed into virtual EDx and Open Courseware (OCW) courses at MIT and a series of handbooks and guides that promote techniques and strategies for effective visual communication. So much research now is interdisciplinary and we must find a way to communicate with one another. I am convinced that the visual has the potential of being a powerful shared language.

How do you hope readers will use your handbook?

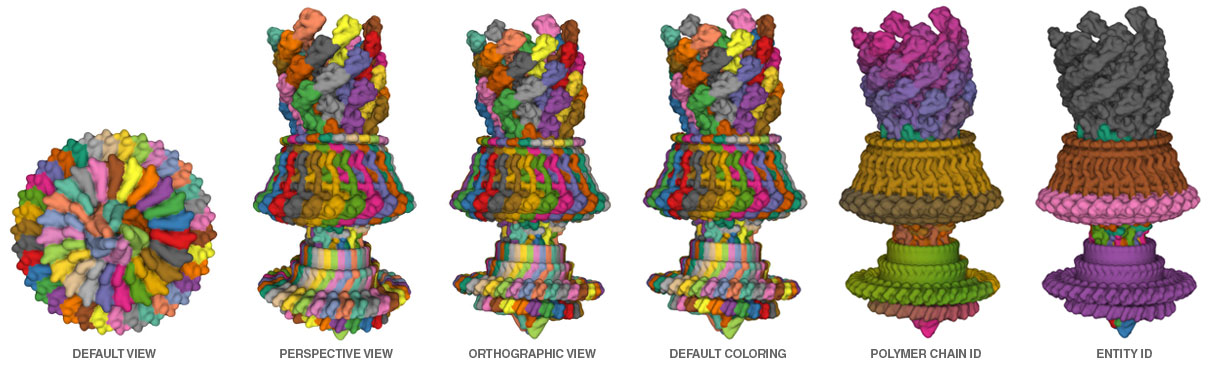

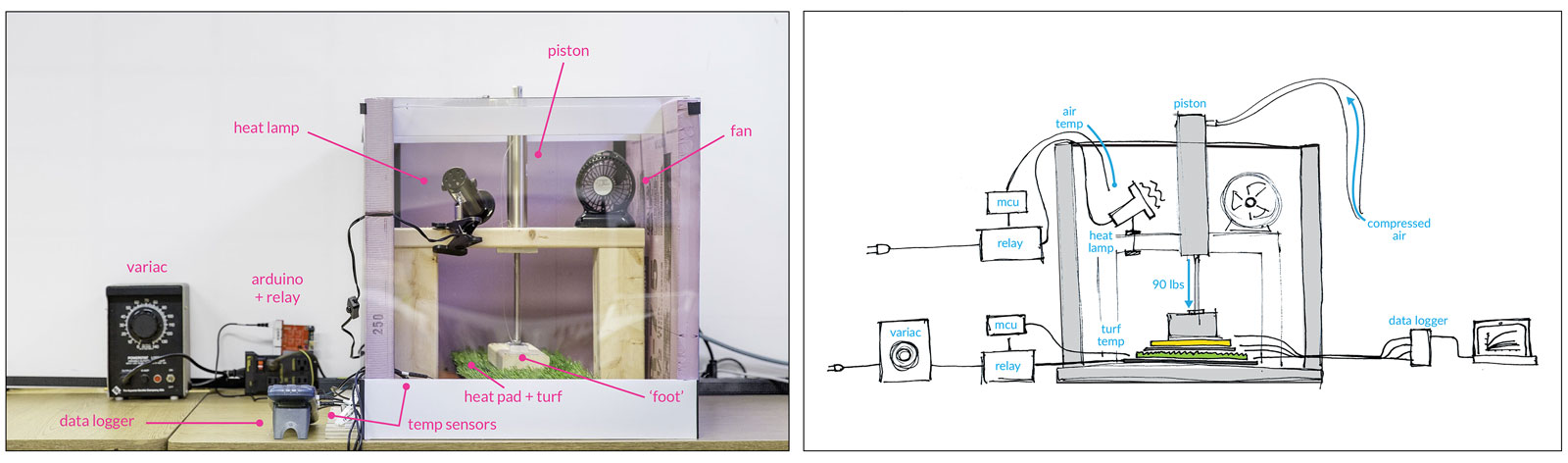

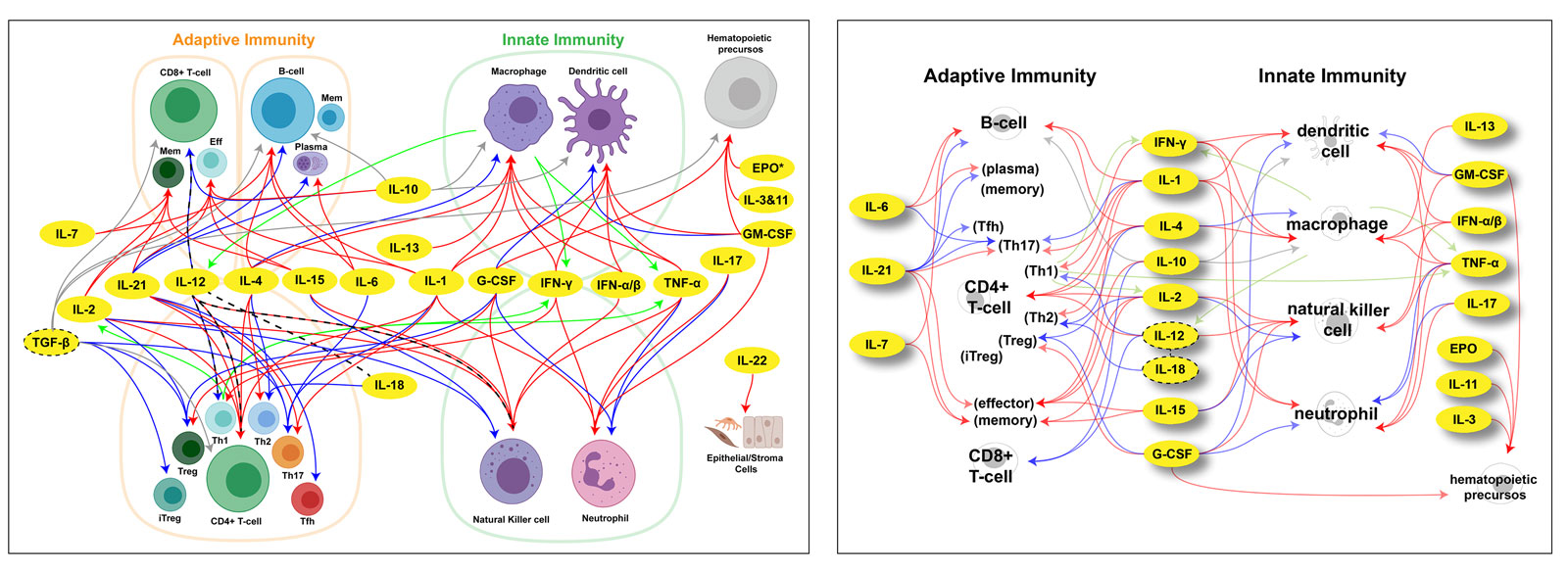

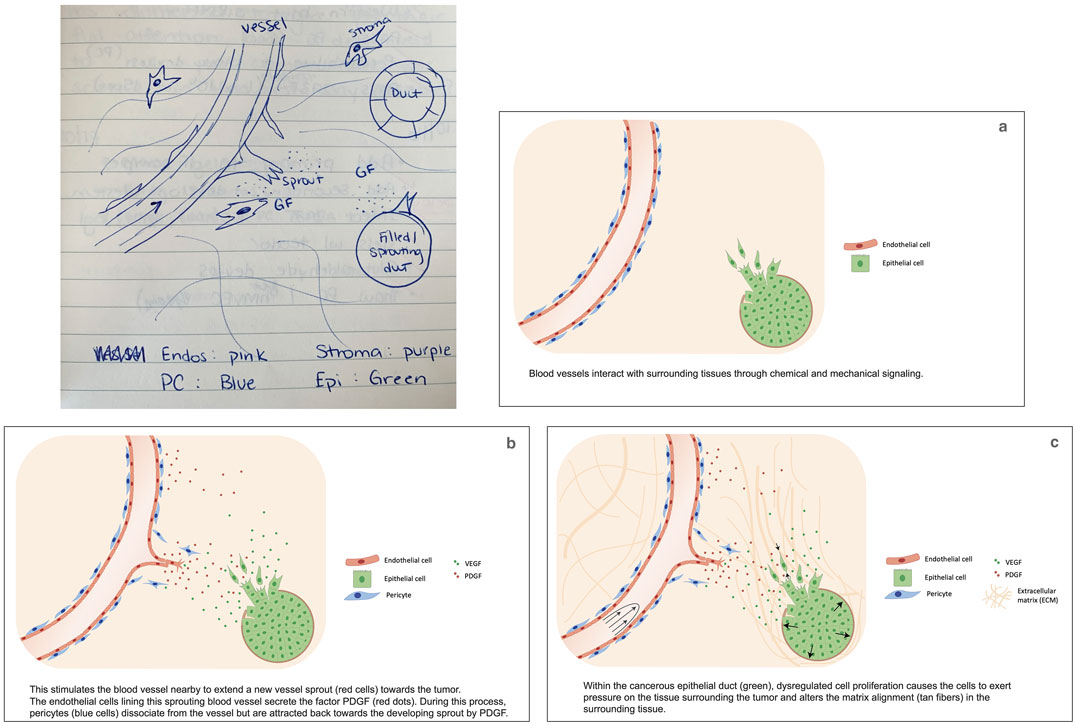

The Design handbook, just like the Photography handbook, is meant to be a quick, easy-to-read, and visually attractive reference book that inspires the research community to pay more attention to how they create their visuals—in this case, their figures, posters, and presentations. Ideally, it would be read early in a new project, so that preparing good visuals is part of the plan from the beginning. The “Case Studies” chapter, in which experts explain the step-by-step decisions that resulted in a particular published final graphic, are particularly instructive. Starting with a "before" figure of the original version, we also have a section showing how a small number of changes brings clarity to the figure.

Photograph courtesy of Felice C. Frankel

Hand sketching is important when working out ideas. When you introduce sketching to digital users, what observations and revelations did they have?

Most graphics these days are made with computational tools, but I am convinced that starting from a pencil and paper sketch pushes each of us to come up with a clarity of concept without the influence of the default features and templates provided by different apps.

For example, always using an app that offers a particular icon to represent a specific component of your graphic, nudges you to think in a particular direction and does not allow you to think about your own visual. And certainly, using a template leaves little room for the researcher to think about the larger design of a figure or poster. For the most part, using a template becomes a lesson in filling space—which is hardly the right approach to creating an engaging poster. They all begin to look alike!

Photograph courtesy of Felice C. Frankel.

What were the major influences in developing your visualization techniques?

The approaches I use were developed in direct response to the common patterns that emerged from our workshops. One ongoing issue in how participants draft figures is that researchers assume the first-time viewer will see what the researcher sees. This outcome is not always the case, especially when you are showing your work to those outside your field. When we meet to look at a figure, I always ask, first and foremost: "What is the first thing you want me to see?" This deceptively simple question often highlights the discrepancy between what an informed or uninformed viewer focuses on. The challenge is that scientists know too much. Another issue that comes up is that many researchers overuse color. Color can be a powerful tool, but too much of it can confuse the viewer.

In drafting this book, did you discover something new that you had not considered before?

The surprise has been that no matter what discipline a researcher is working in, the challenges of visualizing the material are the same. The best workshops are the ones where participants come from all kinds of backgrounds, giving us an interdisciplinary conversation where we can learn from each other. I have also been surprised by how little researchers question the cliched representations that have been perpetuated for years. At the moment, I am working on the third book in the series, Abstraction, which is all about representation. I am having fun with it, and perhaps will annoy a few folks.

Photograph courtesy of Felice C. Frankel.

If you had unlimited funds, what would you create?

Oh boy! What a wonderful question to think about! My immediate response is to create, on every campus, an Envisioning Science and Engineering teaching laboratory, in which experts in various fields of visualization (such as photography, graphics, animation, and data visualization) run workshops for researchers to advance their visuals. We would have programs in visual literacy, raising questions about various published visuals to discuss whether the integrity of the science is maintained. We would question the perpetuated scientific representation to see whether we could find better approaches. We would create new tools to address the growing need for visuals. We would publish an online magazine to keep the research community up to date. We would create a program to encourage and discover ways of communicating to the public—and that’s just for starters!

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.