This Article From Issue

May-June 2017

Volume 105, Number 3

Page 142

I hate ironing; I’ll do more or less anything to avoid it. I started to wonder why those shirts emerged from the clothes dryer looking like a tangled bag of rags.

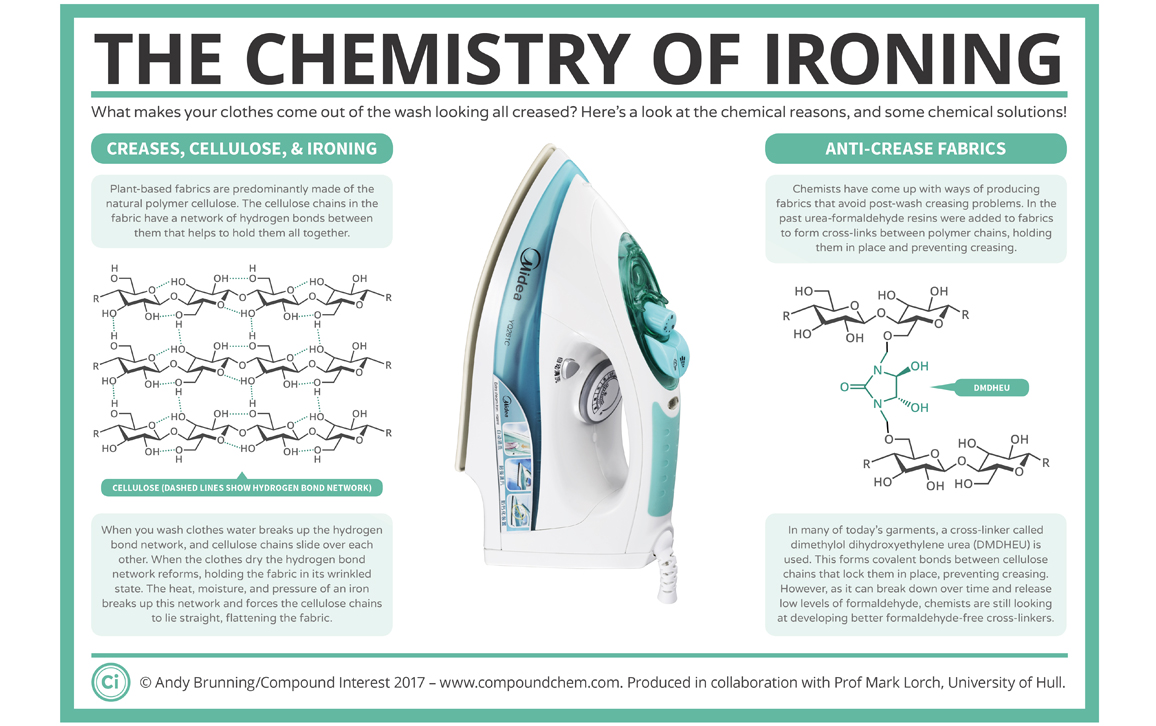

It turns out that the wrinkles in my shirts come down to the chemistry of plant-based fabrics. Cotton, linen, hemp, and so on are predominantly made of cellulose, a polymer that consists of thousands of glucose molecules joined together to form linear chains. Each glucose subunit is “sticky” because it can bind to neighboring cellulose molecules via hydrogen bonds. Individually, these bonds are very weak, but together they form a network that gives the fabric its strength.

These hydrogen bonds are forever breaking and then rapidly reforming. As a result, clothes start taking on the shape that they are left in. As they sit there in a pile, the bonds break and reform, the clothes take up the new shape of the fabric, and the creases are set in place.

Things get even worse when water enters the equation (as it does in the washing machine). Water molecules insert themselves between the cellulose molecules, break up the hydrogen bonds, and act as a lubricant, allowing the cellulose molecules to slide over one another. Then, when the fabric dries, the cotton keeps its now-wrinkled shape.

This is where the hot, steaming iron comes in. The combination of heat and moisture quickly breaks the hydrogen bonds. As I apply these with a bit of pressure, all the cellulose molecules are forced to lie parallel with one another, thereby flattening the cloth.

But what if I want to avoid doing the ironing? I could go with the age-old practice of starching my clothes to keep them crease free. This works because starch is also a polymer made from glucose, so it too can form all those sticky hydrogen bonds. But unlike cellulose, starch is a branched polymer, so it sticks and acts as a scaffolding to hold all the cellulose molecules in place. The drawback is that starch is soluble, so it just comes out in the wash.

What I need is a more permanent version of starch. And that’s exactly what I get in easy-iron clothing. Originally, formaldehyde was used to permanently link cellulose molecules together, stopping them from sliding about and limiting the amount of wrinkles that formed. More recently, formaldehyde has been replaced with friendlier cross-linkers such as dimethylol dihydroxyethyleneurea. The wrinkle-resistant shirts are good in a pinch, but they have a slightly plastic feel that I don’t particularly like, and they still release tiny amounts of formaldehyde, which can irritate the skin.

The pile of laundry is still waiting for me. But at least I have the theory of ironing all straightened out, and so I suppose I’d best just get on with the practical session. Or maybe I’ll go for that crumpled look and just call myself a theoretical ironist. —Mark Lorch

Mark Lorch is a professor of science communication and chemistry at the University of Hull in England. Text excerpted and adapted from The Conversation.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.