This Article From Issue

May-June 2002

Volume 90, Number 3

Page 212

DOI: 10.1511/2002.9.212

In my hand I hold a metal box, festooned with labels, serial numbers, bar codes and tamperproof seals. Inside the box is everything I have written over the past 10 years—articles, a book, memos, notes, programs, letters, e-mail, shopping lists. And there's still plenty of room left for everything I might hope to write in the next 10 years. For an author, it's a little humbling to see so much of a life's work encompassed in a tin box just big enough for a couple dozen pencils.

The metal box, of course, is a disk drive. And it's not even the latest model. This one is a decade old and has a capacity of 120 megabytes, roughly equivalent to 120 million characters of unformatted text. The new disk that will replace it looks much the same—just a little slimmer and sleeker—but it holds a thousand times as much: 120 gigabytes, or 1.2 X 1011 characters of text. That's room enough not only for everything I've ever written but also for everything I've ever read. Here in the palm of one hand is space for a whole intellectual universe—all the words that enter a human mind in a lifetime of reading.

Disk drives have never been the most glamorous components of computer systems. The spotlight shines instead on silicon integrated circuits, with their extraordinary record of sustained exponential growth, doubling the number of devices on a chip every 18 months. But disks have put on a growth spurt of their own, first matching the pace of semiconductor development and then surpassing it; over the past five years, disk capacity has been doubling every year. Even technological optimists have been taken by surprise. Mechanical contraptions that whir and click, and that have to be assembled piece by piece, are not supposed to overtake the silent, no-moving-parts integrated circuit.

Apart from cheering at the march of progress, there's another reason for taking a closer look at the evolution of the disk drive. Storage capacity is surely going to continue increasing, at least for another decade. Those little gray boxes will hold not just gigabytes but terabytes and someday maybe petabytes. (The very word sounds like a Marx Brothers joke!) We will have at our fingertips an information storehouse the size of a university library. But what will we keep in those vast, bit-strewn corridors, and how will we ever find anything we put there? Whatever the answers, the disk drive is about to emerge from the shadows and transform the way we deal with information in daily life.

Painted Platters

The first disk drive was built in 1956 by IBM, as part of a business machine called RAMAC (for Random Access Method of Accounting and Control). The RAMAC drive was housed in a cabinet the size of a refrigerator and powered by a motor that could have run a small cement mixer. The core of the device was a stack of 50 aluminum platters coated on both sides with a brown film of iron oxide. The disks were two feet in diameter and turned at 1,200 rpm. A pair of pneumatically controlled read-write heads would ratchet up and down to reach a specific disk, as in a juke box; then the heads moved radially to access information at a designated position on the selected disk. Each side of each disk had 100 circular data tracks, each of which could hold 500 characters. Thus the entire drive unit had a capacity of five megabytes—barely enough nowadays for a couple of MP3 tunes.

Photograph courtesy of Albert S. Hoagland of the Magnetic Disk Heritage Center in San Jose, http://www.mdhc.scu.edu.

RAMAC was designed in a small laboratory in San Jose, California, headed by Reynold B. Johnson, who has told some stories about the early days of the project. The magnetic coating on the disks was made by mixing powdered iron oxide into paint, Johnson says; it was essentially the same paint used on the Golden Gate Bridge. To produce a smooth layer, the paint was filtered through a silk stocking and then poured onto the spinning disk from a Dixie cup.

Although the silk stockings and Dixie cups are gone, the basic principles of magnetic-disk storage have changed remarkably little since the 1950s. That was the era of vacuum tubes, ferrite-core memories and punch cards, all of which have been displaced by quite different technologies. But the latest disk drives still work much like the very first ones, with read and write heads flitting over the surface of spinning platters. David A. Thompson and John S. Best of IBM write: "An engineer from the original RAMAC project of 1956 would have no problem understanding a description of a modern disk drive."

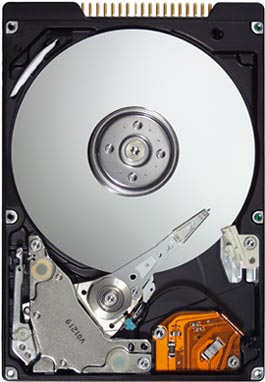

The persistence of the basic mechanism makes the quantitative progress all the more striking. Compare the RAMAC with a recent disk drive, also from IBM, called the Deskstar 120GXP. The new drive has just three platters instead of 50, and they are only three-and-a-half inches in diameter—more like coasters than platters—but in aggregate they store 120 gigabytes. Thus the surface area of the disks has shrunk by a factor of almost 800 while their information capacity has increased 24,000 times; it follows that the areal density (the number of bits per square inch) has grown by a factor of about 19 million.

Low-Flying Heads

A disk drive records information in a pattern of magnetized regions on the disk surface. The most obvious encoding would represent binary 0s and 1s by regions magnetized in opposite directions, but that's not the way it's done in practice. Instead a 1 is represented by a transition between opposite states of magnetization, and a 0 is the absence of such a flux reversal. Each spot where a transition might or might not be found is called a bit cell. Boosting the areal density of the disk is a matter of making the bit cells smaller and packing them closer together.

Photograph courtesy of Albert S. Hoagland of the Magnetic Disk Heritage Center in San Jose, http://www.mdhc.scu.edu.

Small bit cells require small read and write heads. (You can't make tiny marks with a fat crayon.) Equally important, the heads must be brought very close to the disk surface, so that the magnetic fields cannot spread out in space. The heads of the RAMAC drive hovered 25 micrometers above the disk on a layer of compressed air, jetting from nozzles on the flat surface of the heads. The next generation of drives dispensed with the air compressor: The underside of the head was shaped so that it would fly on the stream of air entrained by the spinning disk. All modern heads rely on this aerodynamic principle, and they fly very low indeed, buzzing the terrain at a height of 10 or 15 nanometers. At this scale, a bacterial cell adhering to the disk would be a boulder-like obstacle. For comparison, the gate length of the smallest silicon transistors is about 20 nanometers.

Achieving such low-altitude flight calls for special attention to the disk as well as the heads. Obviously the surface must be flat and smooth. As a magnetic coating material, bridge paint gave way some time ago to electroplated and vacuum-sputtered layers of metallic alloys, made up of cobalt, platinum, chromium and boron. The aluminum substrate has lately been replaced by glass, which is stiffer and easier to polish to the required tolerances. The mirror-bright recording surface is protected by a diamondlike overcoat of carbon and a film of lubricant so finely dispersed that the average thickness is less than one molecule.

Much of the progress in disk data density can be attributed to simple scaling: making everything smaller, and then adjusting related variables such as velocities and voltages to suit. But there have also been a few pivotal discontinuities in the evolution of the disk drive. Originally, a single head was used for both writing and reading. This dual-function head was an inductive device, with a coil of wire wrapped around a toroidal armature. In write mode, an electric current in the coil produced a magnetic field; in read mode, flux transitions in the recorded track induced a current in the coil. Today, inductive heads are still used for writing, but read heads are separate, and they operate on a totally different physical principle.

With an inductive read head, the magnitude of the induced current dwindles away as the bit cell is made smaller. By the late 1980s, this effect was limiting data density. The solution was the magnetoresistive head, based on materials whose electrical resistance changes in the presence of a magnetic field. IBM announced the first disk drive equipped with a magnetoresistive head in 1991 and then in 1997 introduced an even more sensitive head, based on the "giant magnetoresistive" effect, which exploits a quantum mechanical interaction between the magnetic field and an electron's spin.

On a graph charting the growth of disk density over time, these two events appear as conspicuous inflection points. Throughout the 1970s and '80s, bit density increased at a compounded rate of about 25 percent per year (which implies a doubling time of roughly three years). After 1991 the annual growth rate jumped to 60 percent (an 18-month doubling time), and after 1997 to 100 percent (a one-year doubling time). If the earlier growth rate had persisted, a state-of-the-art disk drive today would hold just 1 gigabyte instead of more than 100.

The rise in density has been mirrored by an equally dramatic fall in price. Storing a megabyte of data in the 1956 RAMAC cost about $10,000. By the early 1980s the cost had fallen to $100, and then in the mid-1990s reached $1. The trend got steeper after that, and today the price of disk storage is headed down toward a tenth of a penny per megabyte, or equivalently a dollar a gigabyte. It is now well below the cost of paper.

Electromagnetism

Exponential growth in data density cannot continue forever. Sooner or later, some barrier to further progress will prove inelastic and immovable. But magnetic disk technology has not yet reached that plateau.

The impediment that most worries disk-drive builders is called the superparamagnetic limit. The underlying problem is that "permanent magnetism" isn't really permanent; thermal fluctuations can swap north and south poles. For a macroscopic magnet, such a spontaneous reversal is extremely improbable, but when bit cells get small enough that the energy in the magnetic field is comparable to the thermal energy of the atoms, stored information is quickly randomized.

Brian Hayes

The peril of superparamagnetism has threatened for decades—and repeatedly been averted. The straightforward remedy is to adopt magnetic materials of higher coercivity, meaning they are harder both to magnetize and to demagnetize. The tradeoff is the need for a beefier write head. The latest generation of drives exploits a subtler effect. The disk surface has two layers of ferromagnetic alloy separated by a thin film of the element ruthenium. In each bit cell, the domains above and below the ruthenium barrier are magnetized in opposite directions, an arrangement that enhances thermal stability. A ruthenium film just three atoms deep provides the antiferromagnetic coupling between the two domains. Ruthenium-laced disks now on the market have a data density of 34 gigabits per square inch. In laboratory demonstrations both IBM and Fujitsu have attained 100 gigabits per square inch, which should be adequate for total drive capacities of 400 gigabytes or more. Perhaps further refinements will put the terabyte milepost within reach.

Brian Hayes

When conventional disk technology finally tops out, several more-exotic alternatives await. A perennial candidate is called perpendicular recording. All present disks are written longitudinally, with bit cells lying in the plane of the disk; the hope is that bit cells perpendicular to the disk surface could be packed tighter. Another possibility is patterned media, where the bit cells are predefined as isolated magnetic domains in a nonmagnetic matrix. Other schemes propose thermally or optically assisted magnetic recording, or adapt the atomic-force microscope to store information at the scale of individual atoms.

There's no guarantee that any of these ideas will succeed, but predicting an abrupt halt to progress in disk technology seems even riskier than supposing that exponential growth will continue for another decade. Extrapolating the steep trend line of the past five years predicts a thousandfold increase in capacity by about 2012; in other words, today's 120-gigabyte drive becomes a 120-terabyte unit. If the annual growth rate falls back to 60 percent, the same factor-of-1,000 increase would take 15 years.

My Cup Runneth Under

Something more than ongoing technological progress is needed to make multiterabyte disks a reality. We also need the data to fill them.

A few people and organizations already have a demonstrated need for such colossal storage capacity. Several experiments in physics, astronomy and the earth sciences will generate petabytes of data in the next few years, and so will some businesses. But these are not mass markets. The economics of disk-drive manufacturing require selling disks by the hundred million, and that can happen only if everybody wants one.

Suppose I could reach into the future and hand you a 120-terabyte drive right now. What would you put on it? You might start by copying over everything on your present disk—all the software and documents you've been accumulating over the years—your digital universe. Okay. Now what will you do with the other 119.9 terabytes?

A cynic's retort might be that installing the 2012 edition of Microsoft Windows will take care of the rest, but I don't believe it's true. "Software bloat" has reached impressive proportions, but it still lags far behind the recent growth rate in disk capacity. Operating systems and other software will occupy only a tiny corner of the disk drive. If the rest of the space is to be filled, it will have to be with data rather than programs.

One certainty is that you will not fill the void with personal jottings or reading matter. In round numbers, a book is a megabyte. If you read one book a day, every day of your life, for 80 years, your personal library will amount to less than 30 gigabytes, which still leaves you with more than 119 terabytes of empty space. To fill any appreciable fraction of the drive with text, you'll need to acquire a major research library. The Library of Congress would be a good candidate. It is said to hold 24 million volumes, which would take up a fifth of your disk (or even more if you choose a fancier format than plain text).

Other kinds of information are bulkier than text. A picture, for example, is worth much more than a thousand words; for high-resolution images a round-number allocation might be 10 megabytes each. How many such pictures can a person look at in a lifetime? I can only guess, but 100 images a day certainly ought to be enough for a family album. After 80 years, that collection of snapshots would add up to 30 terabytes.

What about music? MP3 audio files run a megabyte a minute, more or less. At that rate, a lifetime of listening—24 hours a day, 7 days a week for 80 years—would consume 42 terabytes of disk space.

The one kind of content that might possibly overflow a 120-terabyte disk is video. In the format used on DVDs, the data rate is about 2 gigabytes per hour. Thus the 120-terabyte disk will hold some 60,000 hours worth of movies; if you want to watch them all day and all night without a break for popcorn, they will last somewhat less than seven years. (For a full lifetime of video, you'll have to wait for the petabyte drive.)

The fact that video consumes so much more storage volume than other media suggests that the true future of the disk drive may lie not in the computer but in the TiVo box and other appliances that plug into the TV. Or maybe the destiny of the computer itself is to become such a "digital hub" (as Steve Jobs describes it). Thus all the elegant science and engineering of the disk drive—the aerodynamic heads, the magnetoresistive sensors, the ruthenium film—has its ultimate fulfillment in replaying soap operas and old Star Trek episodes.

David Thompson, now retired from IBM, offers a more personal vision of the disk drive as video appurtenance. With cameras mounted on eyeglass frames, he suggests, we can document every moment of our lives and create a second-by-second digital diary. "There won't be any reason ever to forget anything anymore," he says. Vannevar Bush had a similar idea 50 years ago, though in that era the promising storage medium was microfilm rather than magnetic disks.

Information Wants to Be Free

I have some further questions about life in the terabyte era. Except for video, it's not clear how to get all those trillions of bytes onto a disk in the first place. No one is going to type it, or copy it from 180,000 CD-ROMs. Suppose it comes over the Internet. With a T1 connection, running steadily at top speed, it would take nearly 20 years to fill up 120 terabytes. Of course a decade from now everyone may have a link much faster than a T1 line, but such an increase in bandwidth cuts both ways. With better communication, there is less need to keep local copies of information. For the very reason that you can download anything, you don't need to.

The economic implications are also perplexing. Suppose you have identified 120 terabytes of data that you would like to have on your laptop, and you have a physical means of transferring the files. How will you pay for it all? At current prices, buying 120 million books or 40 million songs or 30,000 movies would put a strain on most family budgets. Thus the real limit on practical disk-drive capacity may have nothing to do with superparamagnetism; it may simply be the cost of content.

On the other hand, it's also possible that the economic lever will act in the other direction. Recent controversies over intellectual property rights suggest that restricting the flow of bits by either legal or technical means is going to be very difficult in a world of abundant digital storage and bandwidth. Setting the price of information far above the cost of its physical medium is at best a metastable situation; it probably cannot last indefinitely. A musician may well resent the idea that the economic value of her work is determined by something so remote and arcane as the dimensions of bit cells on plated glass disks, but this is hardly the first time that recording and communications technologies have altered the economics of the creative arts; consider the phonograph and the radio.

Still another nagging question is how anyone will be able to organize and make sense of a personal archive amounting to 120 terabytes. Computer file systems and the human interface to them are already creaking under the strain of managing a few gigabytes; using the same tools to index the Library of Congress is unthinkable. Perhaps this is the other side of the economic equation: Information itself becomes free (or do I mean worthless?), but metadata—the means of organizing information—is priceless.

The notion that we may soon have a surplus of disk capacity is profoundly counterintuitive. A well-known corollary of Parkinson's Law says that data, like everything else, always expands to fill the volume allotted to it. Shortage of storage space has been a constant of human history; I have never met anyone who had a hard time filling up closets or bookshelves or file cabinets. But closets and bookshelves and file cabinets don't double in size every year. Now it seems we face a curious Malthusian catastrophe of the information economy: The products of human creativity grow only arithmetically, whereas the capacity to store and distribute them increases geometrically. The human imagination can't keep up.

Or maybe it's only my imagination that can't keep up.

© Brian Hayes

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.