This Article From Issue

January-February 1999

Volume 87, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/1999.16.0

The Garden of Ediacara: Discovering the First Complex Life. Mark A. S. McMenamin. xii + 295 pp. Columbia University Press, 1998. $29.95.

Paleontologists search for many Holy Grails surrounding a creature or event and in turn indirectly draw as much attention to themselves as their science. The largest beast and the fiercest creature are such grails—and sexy to the news media. One of the other grails is that of the earliest—hominid, dinosaur or, in The Garden of Ediacara by Mark McMenamin of Mount Holyoke College, the earliest life forms. Because there is nothing analogous to so many of these creatures, their interpretation requires the student to possess a wide array of expertise. Chemistry and cell development, taphonomy and stratigraphy are but a few of the mental file cabinets from which data must be retrieved. Interpreting all these facets fluently is crucial to garner support and interest. Unfortunately, despite the obvious knowledge and success of its author, The Garden of Ediacara falls short.

From The Garden of Ediacara.

Maybe McMenamin's book was not written for the general yet scientifically interested populace? It starts out as if it were. In a simple, often biographical tone, the early chapters define the problems of this enduring puzzle: Is it plant, animal, trace or fossil wannabe? What follows are general descriptions of some of the major Ediacaran groups. A number of these are indeterminate, seemingly unrelated in appearance to anything we can normally comprehend. Such descriptions as Dickinsonia rex being shaped like "a beaver's paddle" provide some visual comprehension. The succeeding chapters are filled with excerpts (some unwarranted) of field notes describing collecting excursions to such places as Namibia. These treks down Memory Lane are interspersed with work in the more regulated world of academic life, summarizing the paleogeography of earth hundreds of millions of years ago. New ideas are announced or expanded from technical descriptions, like that of the unusual cell division that McMenamin suggests is responsible for the variety of shapes of this biota, or his argument for a "neovitalistic view of evolutionary change."

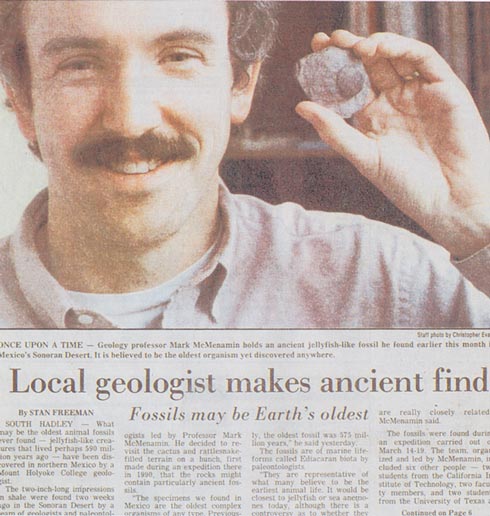

The public reception of these results is also touched on when McMenamin discusses the "world's oldest Ediacaran fossils." The role of the press in scientific endeavors is provided with commentary. It is hard to understand, however, McMenamin's purpose for listing nearly a full page of newspaper references that carried the "earliest" story.

Every chapter ends with numerous citations, referring to related articles, some explanatory piece or personal commentary. Yet the continual use of not-so-common Latin names of animals and, in some cases, the lack of definitions throughout the text hint at an alternate focus of the book: that it is geared more for a scientific audience. Added to this are proposals for new and reconfigured geological sections, the Lipalian and Sinian systems, preceding the Cambrian, or the description in the appendix of a new genus and species of Petalonanae (Kingdom Vendobionta). A semi-popular book, lacking a full peer review, seems an unusual place for this material. McMenamin should know that this is not typical. (When a colleague of his published a description of a new species in American Scientist, McMenamin described it as a "very unusual place" to do so.)

Disregard for the norm seems comfortable for McMenamin, and this is what concerns me most. Releasing full interpretive data to the press before the peer-review process has even begun, as he did with his earliest Ediacarans, is a dangerous path. "My feeling is that we should get the results out to the public quickly," he says, "thus helping to keep enthusiasm high for the kind of work we do." This statement seems more self-serving than anything else.

If the direction and focus of the book were clear, many of the concerns outlined here could be dismissed. The origin-of-life mystery is a wonderful story. The detectives, including McMenamin, who work on this problem should be congratulated for their perseverance and imagination. But translating this series of complex information requires patience, clarity and humility, all of which are somewhat lacking in The Garden of Ediacara.—Tim Tokaryk, paleontologist, Eastend, Saskatchewan, Canada

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.